Bio-libertarianism, Meat-Lego Gnosticism, and other matters

Review of Feminism Against Progress, by Mary Harrington, 2023, Regnery Press, 250 pages.

Today, love is being positivized into sexuality, and, by the same token, subjected to a commandment to perform. Sex means achievement and performance. And sexiness represents capital to be increased. The body — with its display value — has become a commodity. At the same time, the Other is being sexualized into an object for procuring arousal. When otherness is stripped from the Other one cannot love — on can only consume.

— Byung-Chul Han, The Agony of Eros

I’m very grateful for feminism, of which I became aware around 1973, and of which I undertook an intensely prolonged study, beginning around 1993. Having said that, I need to preface this book review by saying that (1) feminism is a big word with a lot of variation banging around inside it, and (2) that my own standpoint on feminism — having first undertaken that deep dive thirty years ago — is colored by my anachronism, both as a 71-year-old man in 2023 and as someone whose understanding of politics flowered, after a career in the Army and at the age of 43, within my participation in what nowadays would be called the Old Left.

I say I’m grateful for feminism, because, speaking personally and as a sort of gonzo social critic, feminism provided me a perspective from which I gained a better understanding of my own former life as a soldier — in particular, the ways in which I had pursued an especially violent form of masculinity constructed as conquest. In fact, this violent masculinity was the subject of two of my own books, Borderline and Tough Gynes.

In the course of my engagement with feminism, and as (then) a Marxist (“not the fun kind,” to crib a phrase from Andrea Dworkin), I was also immersed in the sometimes sororicidal antagonisms inside the big tent of “feminism” — what Mary Harrington calls “feminism’s fractious multiplicity.” And I took against two “schools” of feminism: the liberals and the post-structuralists. My sympathies were far more aligned with the “Marxist-feminists,” the “materialist-feminists,” and some of the “radical feminists.” This was inauspicious in a sense, because just as I was taking up with these various left-feminists and opposing the liberals and post-structuralists, the latter two gained a kind of cultural hegemony, the liberals in politics and entertainment and the post-structrualist in the Academy. The old-lefties and the rad-fems were cast into the outer darkness.

The “left” itself — which meant something different then than it appears to mean now — had tucked tail and withdrawn into the Academy, too — an Academy of which I’ve not been a member . Within a very few years, I watched so-called Marxists abandon their materialism for Butlerian sophistry and, in the vernacular term of my Southern heritage, “fall for the okey-doke” of disembodied post-structuralist twaddle and petit bourgeois sexual libertinism.

Judith Butler has nothing to say to me. As to some of her intellectual offspring, I find it hard to take seriously something called “feminism” that denies the existence of its subject — women. But feminism need not be about performance, or power-struggles, or “deconstruction.” It can also be about assuming the standpoints of women — seeing with women’s eyes — and about protecting the legitimate interests of women. To this day, I’m indebted to feminists Barbara Duden, Vandana Shiva, Maria Mies, Carolyn Merchant, and others. I’m also becoming a fan of Mary Harrington.

Just for the record, and to wind up this standpoint preface, I’m not writing any longer as a Marxist, but as a practicing Catholic-convert who’ s been heavily influenced by one of Mary Harrington’s intellectual handholds: Ivan Illich — someone I myself was put onto by, of all people, a radical feminist friend who had an abiding interest in ecological issues. In the immortal words of the Grateful Dead, “what a long, strange trip it’s been.”

Now, to the book.

One of Mary Harrington’s colleagues referred to her as “the coinage queen,” and I want to second that by saying the she is, in my view, a gifted writer with a penchant for the pithy and memorable phrase. One of her chapters is called “Meat-Lego Gnosticism.” Even if it takes a bit of an effort to get one’s had around it (“gnosticism” is so not part of popular parlance), the phrase — like many of hers — is altogether sticky. Like “cyborg theocracy.” “Bio-libertarianism.” “Limbic limbo.” She puts these little post-it notes in your head.

Feminism Against Progress is more than merely catchy; it’s what some might call important. That’s to say, it arrives at a time and place where it can and should have import. It signifies something consequential. It makes legible something about the zeitgeist that people sense, something which discomfits them, and gives this something the language with which to get hold of it.

That something is a metaphysical and spiritual crisis. Modernity, for lack of a better term, including “post-modernity,” has run into an historical impasse. We’re discovering, to our dismay, that the old truism is indeed brutally true: “Anything that can’t go on forever, won’t.”

Feminism Against Progress helps us navigate some of this impasse.

How many of us have heard the claim, “You can’t stop progress”? It’s something I’ve heard all my life, an article of late modern faith. Nonetheless — and it’s harder each day to ignore — “progress” is swiftly stopping itself. Change, for a time, looked like growth and maturity. Now it appears more like the decomposition of a corpse.

When Mary Harrington named her book Feminism Against Progress, she named and unpacked the discomfort many of us feel even as we cling to the myth of progress in the face of this decomposition.

Harrington’s biographical and conceptual starting points are the same: motherhood. The biggest blind spot in most forms of feminism — and this was a point made by Maria Mies in 1986 — is its inattention (and sometimes even hostility) to motherhood. And yet, in the US (and I presume in Harrington’s UK) almost nine out of ten women who survive until they are forty will become mothers. The worldwide numbers are difficult to access, but one can presume that women who become mothers are still in the overwhelming majority. Motherhood is one of the most universal experiences of women across time, place, and culture. The late modern feminist anti-natalist bias (no, not all feminists) may have a something to do with why less than a third of American women identify themselves as feminists, in spite of the fact that those same women embrace and would ferociously defend some basic social benefits attained by “feminists,” like the franchise, the criminalization of marital rape, access to professions, and so on.

Motherhood is perhaps the most dangerous phenomenon in the world with respect to the ideological claim that each human being is an “autonomous individual.” Every single one of us was born of a woman. The earliest advocates of liberal autonomy (reserved then for men) set women apart from this new form of citizenship, by — as Maria Mies noted — defining women into the very Nature that was subject to male conquest. Men were cultural, women natural. That way all the messiness of gestation, nursing, and whatnot were defined out of culture and politics. Harrington cites Rousseau on precisely this account. She narrates her own story of conversion from “freedom” feminism to “interdependence” feminism, having given birth to her daughter as the story’s inflection point.

“Before I had a child,” she writes on the first page,

“. . . I had no idea how I’d feel once she was there, though I had a dim sense that pregnancy and birth usually do something far-reaching to the emotional landscapes of women who experience it. Even so, the starkness of the contrast between how I’d experienced the world previously, and how I experienced it once my daughter was in my life, still took me by surprise.” (p. 3)

Being pregnant, giving birth, and caring for a helpless infant were the experiences which burned away, once and for all, any residue of her belief in the “autonomous individual.”

The autonomous individual is a political fiction. It takes a kind of sham gullibility, on our parts, too, to separate this mendacity from our daily lives even as we continue to project it onto politics. Every one of us begins within the body of a mother; every one of us would soon die after birth without constant attention and care; most of us begin our post-natal feeding directly from the body of a woman. All of us, at one point or another, even in our adult lives, passes through periods of vulnerability and dependence in sickness, injury, disability, and old age. No actual person can live without others. Mothers are a constant reminder that the emperor of “the autonomous individual” is as naked as that newborn.

Perhaps the most important thing Harrington does in this book — and the most subversive — is to historicize the overly-diffusive term “feminism.” Feminism — in each of its guises —originated as a response to a very specific set of historical developments, first to industrialized capitalism and its attendant political philosophy, liberalism.

“Rather than feminism being evidence of progress,” she says in an interview, “feminism is an effect of technological progress.”

In her second chapter, “Feminism, Aborted,” she cites Karl Marx, Karl Polanyi, and Ivan Illich— especially Illich — to upend much pop-historical errata with regard to gender, in an earlier sense. Marx ties the emergence of ideas to contextualizing material conditions which correspond to those ideas. Polanyi’s shows us the importance of social “embeddedness.” Illich shows us how “vernacular” culture — household production — is opposed to the factory systems that displaced and eventually destroyed it.

Likewise, Harrington subjects “patriarchy,” as the reified enemy of “feminism,” to an historical cross-examination. There is no transhistorical phenomenon, she says, which can be summarized as “patriarchy.” The contexts and forms of normative relations between men and women were distinct. The contexts that gave rise to modern feminism were specifically and inevitably the permutations of modernity itself, especially the combined processes of industrialization and urbanization, which — with increasing political and cultural centralization under the rule of capital — engendered a process of cultural homogenization and leveling.

The unexamined premise in the construction of transhistorical “patriarchy,” is that the only real social power is formal or legal power. She exposes this is self-evidently wrong. Women have always exercised agency and power, though not always through legal and formal mechanisms. In terms of women’s “agency” (I’m learning to hate that term), dignity, and skilled significance, a subsistence farm is far better than a factory, where she is reduced to a de-skilled and interchangeable part.

This writer/reviewer, as an Illich devotee, very much appreciates the Illich in Mary Harrington. Illich’s book, Gender, landed him in very hot water with many feminists, who took it to mean he opposed the interests of women (defined by his critics as liberal freedom). In fact, that was not what he was on about at all. He saw the liberal attempt to reduce human beings into a mass of interchangeable parts as a danger to community and a boon to capital. Harrington calls this reduction of people into interchangeable parts the “liquefaction” of human nature. Korean-German philosopher Byung-Chul Han calls this “the inferno of the same,” abandoning the deracinated person, as Lacan might say, to “the abyss of pure subjectivity.” Nonetheless . . .

This triumph over human nature hasn’t been as complete as its 20th-century visionaries might have wished. Whether at the small or large scale, human nature refuses to be entirely liquefied. And this resistance prompts increasingly frenzied efforts by the proponents of liquefaction-as-progress to stamp out the last traces of resistance. This can be seen across countless areas, but I’ll discuss three in particular: the drive to liquefy sexual intimacy, the effort to interrupt the bond between women and children, and the push for medical victory by a disembodied ‘self’ over the flesh that ‘self’ inhabits . . . liquefaction doesn’t free us from normative, embodied patterns of behavior or inclination. Rather, it dissolves social codes developed over millennia to manage such patterns and re-orders the still-existing patterns to the logic of the market. (Harrington, p. 79)

As to Illich, he was referring to the various forms of complementarity and interdependence which exist within a given and created Being. He called this fitted-ness, “proportionality.” Proportionality was attacked (and in many respects destroyed) by modernity’s “war on subsistence,” its war on enchantment, and it’s war on the transcendent. “Liquefaction” is the dissolution of those “fittings,” those relations out of which we discern meaning. Creation was dissolved, liquefied, in order to conquer and strip mine it. This dissolution of the “proportional” relations that constitute the order of Being, this “sense of fit,” is prerequisite for redefining nature as a basket of resources, including human beings (“human resources”), in order to reassemble everything as commodities or externalize them as “waste.” The final thing to be commodified is us.

For all the worlds before our own, at least all of those of which I know anything, it is a certainty that there is a correspondence between what is here and what is beyond. Heaven is mirrored by earth. The baby I saw in a woman’s arms yesterday is a cosmos, a microcosmos. When I look at this baby, I see something which appears, at first sight, utterly dysymmetric from what I see when I look up at the stars, and yet they fit at every point. They are both complementary and mutually constitutive, that is, the existence of one implies the other. Each people discerns this complementarity through a specially trained gaze which anthropologists call culture, though I would rather speak of it as the art of seeing the cosmos, bearing it, suffering it, and enjoying it. The assumption that the world is a net of correspondences is the background, the magma which all circum-Mediterranean cultures presuppose; and, in so far as I can understand, this is the same for all Far-Eastern cultures and for the Mexican, Aztec, and Mayan cosmos, of which I know a little bit as well. You cannot enter any of those worlds without the assumption that all existence is the result of a mutually constitutive complementarity between here and there. (Illich, speaking with David Cayley, Rivers North of the Future, p. 132)

Harrington writes:

How did pre-modern women think about their own relations to their children, husbands or communities? The philosopher Ivan Illich argues that the ‘embedded’ relations of pre-modern societies were irreducibly dual not just in material terms — the work men and women did — but also in roles, gestures and so on: every facet of each person’s way of being. For Illich, this ‘vernacular gender’ was concerned not with the subordination of one sex to the other, but in ‘ambiguous complementarity’ in which each depended on the other, just as the ploughman and his wife together perform the vital tasks of a subsistence household. (Harrington, p. 32)

. . .

The ploughman’s wife could point to yarn spun, cheeses made, animals well-tended and so on; material output every bit as indispensable to the household as her husband’s muddy toil in the field. But under the new regime ‘women’s work’ was, as Illich puts it, ‘not only unreported but also impenetrable by the economic searchlight’. Women’s responses to this challenge followed two characteristic patterns. (p. 36)

One early feminist response to the modern industrial domestication of bourgeois women was to make “women’s work in the home more visible and valued.” The other was to demand women’s entry into the market with men. As the “Rights of Man” took hold in civil society alongside the market, and women were likewise disembedded from the old regime of household production, some women demanded inclusion as full Lockean citizens. Harrington provisionally sides with the former, inasmuch as at least acknowledges human interdependence (as opposed to conflict theory), and valued the (private) care-work that was being devalued by (public) market economics.

These two tendencies , as noted— domesticity as an important refuge from the cruelties of the market and the right to compete with men as full Lockean citizens — were bourgeois. Displaced peasants converted into working class women were already “in the market,” some doping their children with opium at home so they could slave all day in some “Satanic mill” of a factory.

The political process the haute bourgeoisie employed in its war on subsistence, to convert land into a mass-production resource (initially for the wool trade) and to simultaneously force the reluctant peasantry into those Satanic mills, was called enclosure; and Harrington uses the idea of enclosure — correctly and with effect — throughout the book to describe the commodification — or in neoliberal terms, “privatization” — of both commons and extra-market or pre-market values. Harrington uses enclosure, the process and not just its original historical instantiation, as one of her key interpretive frameworks throughout the book. Enclosure is the capture and marketization — or commodification — of both nature and people’s lives; and it advances under the banner of freedom.

The land was “enclosed,” converted into a basket of disaggregated (atomized, “liquified”) resources, even as the peasants were proletarianized, converted into human resources (living capital) for the mills —technology-appendages which could produce more value than they were paid (profit). (Un-landed laborers were free to work or starve.)

Enclosure works across registers and fields over time. Capital never sleeps and never stops devouring. Are you trapped by debt? You’ve been enclosed. Is your “love life” directed by a dating app? You’ve been enclosed. Do you have to buy a car to live? You’ve been enclosed. Modern enclosure even employs technology to enclose attention, and, thereby, both desire and will; and through this breach, everything. Find your significant other through a fucking app. Let your phone schedule your life. Enjoy nature through your monitor. Click here in emergencies for a therapeutic intervention. You’re in the wrong body; we’ve got something to sell that can help you with that.

That which is to be enclosed must first be “disembedded,” removed from its context (it’s Illichian proportionality) and thereby stripped of all meaning. Harrington cites Polanyi here. This disembedding process is war, war on those mutual constitutions described by Illich, war on complementarity . . . a war on meaning itself. The author is writing largely about complementarity with regard to sex. The book is about feminism, so it’s necessarily about sex.

Like Louise Perry and Christine Emba, she has taken aim at the so-called “sexual revolution,” a “revolution,” she acerbically points out, which was heartily embraced by such feminist icons as Hugh Hefner.

[The] ‘disembedding’ of sexuality — its unmooring from material limits and implication in social relations — didn’t exactly bring about a new universe of boundless, polymorphous pleasure . . . Much as industrialization enabled the deregulation, enclosure and commodification of productive work, so reproductive technologies enabled the deregulation, enclosure and commodification of sex — and with it, the extension of market society to sexuality, in the creation of a so-called ‘sexual marketplace’. (p. 64)

Market logic shades into the decontextualized and elastic notion of consent in a world where everything is understood in terms of market transaction.

[I]n the act of digitizing human intimacy as options that can be keyword-searched, browsed, selected and consumed, dating apps and websites invite us to consider the search for love as just another online marketplace . . . While this is framed as freedom and empowerment, often accompanied by a celebratory embrace of self-commodification via online or in-person ‘sex-work’, the collapse of sentiment into the market has come with a range of uncounted costs. (p. 69) (emphasis added)

In the sterile and duplicitous vocabulary of “economics,” the uncounted costs are called externalities. Externalization is the refusal to acknowledge anything apart from price and formal consent in the constricted ahistorical context of the transaction itself. The past — from traditions to the conditions of a person’s life that led them to the instant of consent — is the enemy kept outside the gates.

It’s true that the barbarous behavior of some men (in particular) has made consent an aspiration instead of the barest baseline of decency; but, as always, the market turns what is minimal to what is maximal when this conversion bends to the advantage of hucksters, profiteers, and a few privileged dilettantes. As the feminist Carole Pateman observed in writing about contract theory, it is theoretically permissible— given two postulates of late modernity/postmodernity — for someone to sign a contract to become a lifelong slave: (1) the proprietary body, the body understood as a possession of some disembodied self (the autonomous individual shade), and (2) consent, in which all factors prior to and leading up to the moment of consent (signing the contract) are externalized, curtained off from legal and ethical view. In reality, as everyone knows damn well, we “consent” to things all the time under various kinds of duress, which may make it legal, but it’s a far cry from moral or just. Consent is a shit standard, and Mary Harrington has the courage to say so. Nonetheless, this is the sine qua non, the finalis maximus, of liberal “freedom.”

The so-called sexual revolution was defined by this “freedom,” a freedom which uncritically assumed the postulates of autonomous individuality, the proprietary body, and the externalization necessary to conceal the whole sham. With the advent of this so-called revolution . . .

. . . the feminist movement adopted a vision of personhood defined in opposition to interdependence — and thus settled the feminist debate decisively against care, and in favor of autonomy. (p. 30)

And it is here where Harrington calls out one key externalization, another no-man’s-land in contemporary debates within and without feminism: technology. What Bernice Hausman wrote in her history of transsexualism equally applies to hormonal birth control, elective surgical sterilization, chemical suppression of natural puberty, and gender “reassignment” surgery.

Their subject position depends upon a necessary relation to the medical establishment and its discourses. (Hausman, Changing Sex, p. 3)

In the 1970s, Ivan Illich wrote his two most well-known pamphlets on institutionalization, Deschooling Society and Medical Nemesis. In Medical Nemesis, he identified what he called two watersheds in medicine: first, when medicine started doing more good than harm, and second, when medicine became a counter-productive technocratic monopoly. For him counter-production was characterized by iatrogenesis, maladies that are produced by medical practices, like the staph infection caught in the hospital, medicine to offset the side effects of medicine, drug-resistant pathogens, penury from medical bills, political medicalization (“biopolitics”), and so forth. Mary Harrington has identified another, closely related, counter-productive watershed in medicine.

In her words, “We shifted from a restorative to a meliorist medical paradigm.”

Medicine was once aimed at treating dis-orders, like disease, injury, disfigurement, or malfunction. Medicine treated what was out of order or abnormal. At some point — and she identifies the inflection point with hormonal birth control — medicine began to intervene and interfere with healthy natural processes — to “improve on nature.” Medicine began to “treat” what was right.

(In fact, as Hausman shows, the first surgery to “correct” for indeterminate sex happened two years before the FDA approved “the pill.” The surgery was performed on “Agnes,” who was diagnosed as intersexual for presenting male gonads and secondary female sex characteristics (enlarged breasts). Only after the surgery did “she” admit that prior to seeing the physicians, he had been dipping into his mother’s synthetic estrogen supplements since he was twelve years old.)

“Meat-Lego Gnosticism” is the term Harrington coined to describe the trialectic between progress-ideology’s proprietary body, technology, and meliorative medical practice.

Progress-ideology, as previously noted, defines personhood as an autonomous individual ghost who “owns” a body (as opposed to being embodied — as she repeatedly points out, which is apparently not as apparent as it seems, one doesn’t “have” a body; one is a body.) Gnostics want to escape “the body.”

Thinkers particularly in the Roman Catholic tradition condemn the push to master or escape the physical, as a return to the heresy of ‘Gnosticism’. This grouping of esoteric Christian sects, active from around the 2nd century AD until their suppression by the Knights Templar on the 13th century, saw life on earth as irredeemably corrupt and dreamed of returning to a higher world of pure thought.

But in truth what we see today is distinct from the ancient Gnosticism. The Gnostics saw material existence as the work of a malevolent deity, the Demiurge, and sought to transcend the material plane through spiritual wisdom (‘gnosis’). . .

. . . The contemporary phenomenon agrees with the ancient Gnostics on a crucial point: the physical world is evil and arbitrary. Unlike the ancient Gnostics, though, the modern variety seeks to transcend the the physical not through spiritual knowledge but through technology. And its moral vanguard is bio-libertarianism, which views and moral or legal effort to restrict the tech-enabled control of our biology with horror and dismay. (pp. 140–41)

The technologies under review relate primarily to two medical specialties: endocrinology and plastic surgery. Bernice Hausman called her fellow poststructuralists to account in this work of history for their evasion of the fact that these “trans identities” are a product, that the current concept of gender and these new “subjectivities” are fundamentally constituted by technology — that is, by invasive procedures from both of these particular medical specialties.

Elective plastic surgery was, until the late 1950s, considered by the medical establishment to be dangerous quackery (in part because it really was dangerous). Now, as Harrington points out, if one has the financial means, endocrinology and plastic surgery are standing at the ready to give you that Gnostic makeover. This doesn’t only apply to putting kids on puberty blockers or having a fake penis constructed out of your own thigh meat. It’s breast implants or juicing with anabolic steroids. In some cases, among affluent and highly disturbed transhumanists, it’s skull redesign or having a tail added. Furnetics Solutions offers you “morphic otter fur” for $7 million, or a tail at the bargain price of $500,000.

None of this, Harrington notes, is without the other kinds of costs. The humble endocrine birth control pill can bless its consumers with the vaginal spotting, migraines, nausea, breast tenderness, weight gain, mood swings, and reduced sex drive. Long term, it has the added benefit of higher risk for cancer, strokes, and heart attacks. Surgical/endocrine gender “transition” has a host of risks and (often extreme) side effects, tas well as a lifelong dependency on expensive and disruptive drugs to maintain the appearance of having “changed sex.” The ever popular breast implants — popular among women with the desire and the means — reward many recipients with post-op infections, loss of sensation, capsular contracture, rupture or deflation, anaplastic large cell lymphoma, and silicone contamination of breast milk. Yay! Meliorative medicine!

The author recounts some of the obvious awfulness, but her real and justifiable concerns are both political and metaphysical.

As a feminist — someone taking the standpoints and interests of women into account — she shows the ways in which liberal feminism in particular has benefited a small layer of women at the top of the capitalist hierarchy and worked to the detriment of many of the women further down the rungs. Yes, Harrington not only historicizes feminism, she calls our attention back to that archaic notion that died with the left: class.

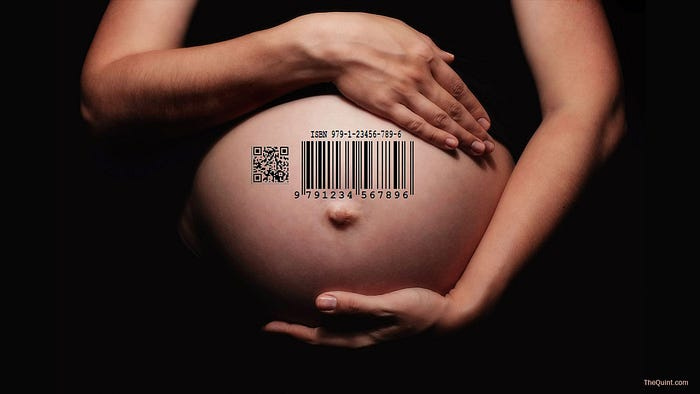

Rich “cyborg priestess,” she points out, who wants to have a child without the pangs of pregnancy and birth can now employ a surrogate — some poorer woman for whom circumstance has led her to commodify and rent her womb. The wombs of poor women have been thereby enclosed so the Kardashians of the world can enjoy this newfound “freedom.”

The metaphysical prerequisite for these practices is the denial that human beings have a form and a nature that goes with it. Without this ideological commitment, acknowledged or not, we couldn’t justify the marketization of body parts and the “deregulation of nature.” (p. 157) Harrington doesn’t just point out that the emperor has no clothes; she says the emperor is monstrous.

[I]f everything that makes us human resides in our consciousness, and there’s nothing natural or integral about our bodies, then we really are just meat. And inert, soul-less meat — living or dead — can legitimately be hacked, spliced with fish-skin or pig or monkey DNA, chopped and remodeled at will, or dismembered for commercial or political ends. At scale, meat can be managed via bio-engineering: modified like battery-farmed poultry to better tolerate poor living conditions, perhaps, or to crave new forms of synthetic protein proposed by futurists as the best means of ensuring adequate food supplies as the human population grows

I don’t want to live in this world. (pp. 160–61)

When we turn inward and ask, “Who and what am I?”, and we find no answer, “identity” is thrown into the empty chasm . . . which, alas, has no bottom.

Harrington doesn’t romanticize the pre-industrial past (as some of her straw-manning critics have perfidiously claimed) and neither did Illich (as many of his straw-manning critics had perfidiously claimed). She (and he) are saying that there were a lot of babies (ahem) thrown out with the bathwater in the march for progress.

Harrington’s theses have attracted patriarchal-restorationist conservatives who want part of what she says and ignore the rest, and she’s been denounced by liberals for her supposed turn against “feminism,” even though the book claims feminism . . . in the title! All these agenda-driven responses are fundamentally dishonest refusals to come to terms with the other point which is apparent from the title: calling bullshit on the myth of progress. In fact, Harrington is an old-leftist without the Promethianism and a radical feminist without the conflict theory — in other words, very close to (if not, I don’t know) a Catholic.

Again, she emphasizes that feminism could only have happened as it did in the specific historical circumstances in which it emerged. It is a by-product of latter modernity, as its fragmentation is also a product of the evolving culture of latter modernity. She says she is not conservative, because there’s nothing left to conserve — that horse already left the barn. She says she’s not progressive, because she recognizes that the myth of progress is lipstick on an ideological pig.

She uses a different word to describe her feminism. Let me preface with my one criticism (apart from no index, grrrr).

In one way, and one way only, reading this book reminded me of the car trips we once made between Hot Springs, Arkansas and Galveston, Texas. It’s a nine hour drive along which you hit long stretches of open highway with a speed limit of 75 miles per hour, punctuated by small towns where the limit abruptly decelerates to 30. Where I kept having to hit the brakes while reading Feminism Against Progress was every time I encountered the term “reactionary feminism.”

This is a dangerous, if also necessary, conversation Harrington has engaged — navigating between the shibboleths of old-right and old-left, new-right and new-left, “progressives” and “reactionaries.” To make one’s point without being captured and put to use by one or another ideological militia requires a lot of “except for’s” and “without the concomitant’s” and “that said’s.” The ground is seeded with metaphysical landmines and muddy slopes. That’s why, as much as I like this book, and as much as I admire Mary Harrington’s work and intellect, and as important as this dangerous conversation is, I’m not altogether okay with the term “reactionary feminism.” Others are, and I could be wrong about this (I work hard to be wrong at least once a day), but here’s my discomfort.

One — she is obviously not a reactionary (except in one very limited sense), even if it’s a vaguely understood epithet she may be using in a comedic, ironic, or provocative sense. There are several definitions of “reactionary,” only one of which is “opposed to progress and liberalism.” (I assume this is hers; it’s in the title after all.) By this definition, I might be a reactionary (though even this is not cut and dried).

For most people, however, this term applies (and too often appeals) to paleoconservatives, brooding integralists, and sometimes outright fascists. In a very real sense, the reactionary-progressive polarity, if claimed for whatever reason, is a reinscription of the ever more anachronistic and incoherent “left-right” continuum. Harrington’s anti-capitalism, for example, is very far from bog-standard Toryism or American conservatism.

Two — related to #1, the term will function like a magnet, attracting at one pole and repelling at the other. Some of those who are attracted to the reactionary part will be quite unsavory (read the comments section at UnHerd); and some of those repelled by it may be convertible given time and patience. (She herself is a contributing editor for UnHerd, a podcast and online publication that might be loosely classified as conservative-heavy post-liberal.)

Three — it’s becoming a brand in the aforesaid economy of attention. Brands have a way of flaming up, then flaming out. Her theses are too urgently necessary to allow their semiotic declension from index to icon to symbol to yesterday’s news.

It’s unfortunate, in my opinion (for what that’s worth), that she raises “reactionary feminism” at one point as a battle streamer in a sub-section called, “It’s war.” I’m no fan of war, even virtual war. I’ve seen the real thing. It’s neither redemptive nor heroic. This four paragraph call to arms is a call — Christ, I’ve heard this all before! — to “build” a movement. (She, happily, more or less takes this back later in the book.) What’s most unfortunate, from this reviewer’s perspective, is that this mini-manifesto is slap-dab in the middle of the book, encased fore and aft by keen observation, good scholarship, sober reflection, and extremely sharp insights.

Mary Harrington herself disclaims that she’s part of what she calls the first-world knowledge-worker class, and admits she’s a long standing inhabitant of the digi-virtual world. This is a world where people can ride waves. This is a world where we can lose touch with the really-real world where feet meet the street. This is a world where ideological affinities — even fragmentary ones — can actually converge in a way for a few people to make their living (for a time). Affinities, however, can turn into self-segregating online ideological cliques. These hazards are built into the medium; and I pray she remains vigilant on this account.

This is a world where her star is rising; and I’m grateful for that. It’s also a world which tends toward the construction of intellectual silos; and these silos are built up around brands. Finally, it’s an ecology of ephemera, a mayfly hatch, where dramatic forms burst into being quickly and disappear just as abruptly. Harrington is too important an organic and public intellectual to be isolated within this milieu (and her book breaks free of that in a sense, being an actual paper book that takes up actual space and requires no electrical current).

The thing about riding a wave is transience; the wave breaks at the top of the ride then flattens at the end. There’s my caution, and I’ll close out my inter-generational carping. It’s still a great book.

Returning to the book now— which I consider part of an emergent and important post-liberal conversation — the strange attractor in this conversation between the refugees of the dead old-left and dying old-right is transgender ideology, which colonized feminism for capital, beginning in earnest in the early 1990s.

Harrington was herself its captive for some time and even went by the name Sebastian for a time. For that reason, she’s harsh in relation to the ideology and very charitable toward the actual people who “identify” as transgendered. For the record, I think this is exactly the right approach; not only because it’s the right thing to do — love people where they are — but because it combats the perfidious polemical claim that those of us who question this ideology are motivated by bigotry and hatred — a scurrilous defamatory claim designed to shun us and shut us up as “terfs,” a brainless, crypto-Stalinist term of abuse (“trans-exclusive radical feminists”).

Harrington shows why and how pop-Butlerist gender ideology and the transgender ideology that sprung up from it has served as a policing mechanism within liberal technocratic circles in support of what she calls “cyborg theocracy.” (Ironic, because Judith Butler herself has been quite critical of “identity politics,” though her drag-performativity politics is even more toothless and off-putting.) Transgender ideology has become a kind of ideological litmus test among capital’s liberal retainer class — which the author calls “knowledge workers” (though it’s spreading like influenza among the young via the internet which has colonized their minds and lives). White collar liberals risk expulsion and demonization from their social circles if they so much as raise a question about this ideology. I know of very few members of the professional managerial class and very few academics who, even in the face of people now allowing the elective sterilization of their own children, will publicly question this orthodoxy. Their ostracization would be swift and terrible. Some would soon be called “fascists,” by the inquisitors of PMC “audit culture.”

Harrington and many of her interlocutors who’ve dared to question it, as well as gender-critical feminists, have found themselves excluded from public conversations by the PMC/academic “left.” (She just recently had her New York book-launch venue cancelled at the behest of online audit-culture mobs.)

This new “left” (ha!) hatched out of the corpse of the older left, which had its roots not among academics but among textile workers, miners, and longshoremen. The only people who are giving Mary Harrington et al the time of day are conservatives and those few outliers who are “economically left and culturally right.” Their appearance with the apostates, in turn, sets her and some of her colleagues up to be branded as . . . well, “reactionaries,” which transposes into “fascists.” Unfair? Indicative of the depth and breadth of liberal stupidity nowadays? Oh, hell yes! But also, unfortunately, for the time being, effective.

Class matters, says Harrington, now we’re on that subject. A somewhat lengthy epistemic detour on demographic statistics first.

The disaggregation of creation divided humans from nature, then dissolved nature into a menu of resources. This is a thought habit found mid-most in the myth of progress, Harrington’s expository target. The nature-nurture controversy is a progressive article of faith as well — which I denounce every chance I get, not because neither exists (they exist in a non-material form as categories), but because in actual human beings these mental categories are inextricably bound in one unbreakable bond. One has to “cut up” the human being, so to speak, to identify said human with these artifices.

Demographic statistics first “cut people up” according to various aspects of their real and integrated existence which are likewise never extricable in that integrated reality. It all begins with that most pernicious of disembodying abstractions, population. X number of “the population” (people) are men, Y number women. A percentage of the population of a given territory are African-derived, B percent European-derived, C Indigenous, D Asian-derived, E=A/B mixed, et cetera et cetera. These kinds of disembodiments, disaggregations, and disembeddings can have some limited uses for creating “pictures” taken from outer space — the Google-maps perspective; but the real and present danger is their reification.

Deleuze might have said that demographic statistics (and we might add internet algorithms) have taken us to a new level of abstraction, a step even beyond the autonomous individual, wherein we have become “dividuals,” (re-embedded in newly disembodied collectives made of sheer numbers) . . . and so the erasure of metaphysical form is complete.

At our house right now, we’re preparing for some potentially violent storms tonight, because meteorologists have refined their craft and technics to such a degree that they can predict patterns, at least for a few days out. This big picture only becomes more granular and practical the closer in time we get. The final outcomes in specific places will be known only within minutes, and the final-final outcomes only after the events. Analogously, demographic statistics only approach the totality of real human lives as they approach actual persons Here and Now; and that distance is never actually closed.

When we begin with the abstraction (population, nature-nurture), then proceed to partialities (age, race, nationality, gender, etc.), we’ve completed two of the three steps required to construct an ideology — what Hannah Arendt called an idea transformed into some self-encased and unquestionable cultural premise, the third element being co-constitutive antagonism. Ideology requires enemies. (A long-form piece here on that.)

Demographic statistics “cut up” human “populations” based on some true(ish) but partial characteristic. (Identity politics does something similar.) Humans are reduced to populations, then populations are reduced to statistical categories — like . . . well Legos, something which can be used to construct, de-construct, and re-construct.

(The idea of construction is one which Harrington is challenging at its core. It’s no wonder the post-structuralists and pop-post-structuralists, who are always on about this or that being socially “constructed,” have targeted her and some of her main interlocutors as “fascists.” The notion of construction (even of our selves) is fundamentally opposed, metaphysically opposed, to the human creature as something given or created.)

Demographics as an anthropology has created all kinds of confusion, including within feminism. When feminists began speaking of the standpoints and interests of women, they almost always projected their own standpoint and experience into theoretical generalizations. Then black feminists challenged white feminists; Marxist feminists challenged liberal feminists; third world feminists challenged first world feminists; and so on. But the thought habit of disaggregation into partialities has been so strong, so axiomatically un-thought, that the only recourse for many feminist theorists, as well as women who loosely identified as feminists, was to introduce another abstraction: intersectionality. These partialities intersect. They still couldn’t escape the gravitational attraction of abstraction and partiality.

I witnessed a woman once, who was on my Facebook feed, one who had a PhD, describe herself as a kind of Frankenstein monster of partialities. “I am a white cis hetero woman with economic privilege . . .” blah blah blah. Not only was this a kind of virtue-performative self-denunciation, it was her own voluntary self-dissection into “intersectional” abstractions. From this description one could discern hardly anything about who she actually was as a living, embodied, embedded human being. I learned a great deal more about her — which made her infinitely more relatable and human — from serial reports about her near-heroic, two-week search for a lost dog (which she found — happy ending).

Class can be taken to describe a partiality, which my Marxist friends do by relating each person to “means of production” (which is never altogether informative or even altogether accurate). Neither I (here) nor Mary Harrington (in the book) are being quite that reductive when we discuss class as position, a situation, and a relation (not an identity — a Lockean notion, btw). Class is not some personal characteristic; but it must be said, position matters and at least circumscribes aspects of our personalities. Class entails situations and practices. (One might call Sherry and me lower-middle-class or working class based on our negative net-worth, a very modest home in a small economically depressed town, and our pensioners incomes, but we’re not going to set up a filing system here for class categories. It’s sure as hell not our “identity.”)

Harrington, thankfully, uses demographics and class comparisons without mis-stepping onto the slippery slope of ideology. She simply points out that the female beneficiaries of progress theology, the sexual revolution, and “meat-Lego-Gnosticism” are women of some means. She calls this “sexual Reaganism,” where the theoretical claims of the trans-humanist and proto-trans-humanist boosters will have benefits envisioned as “trickling down” to the rest of women by and by.

Meat-Lego Gnosticism includes the aforementioned natal surrogacy — rich women renting the wombs of poor women. In the more everyday field, upper-middle-class women hire poorer (often immigrant) women to clean their homes and watch their kids while the more well-to-do “empower” themselves through their professional careers. Even working class women now, those who can’t afford not to take jobs, have to shoulder the cost of daycare centers (staffed by poorer women), which cuts their regular wage to a poverty wage. It turns out that, no matter how its dressed up by elite ideologues, class is still and always a parasitic relation. (These same ideologues, as Harrington points out on page 110, do have an account of parasitism — the “parasite” for them is the unborn child.)

The most visible proponents of transhumanism, and those most captive to its central delusion, are the super-rich. Musk, Zuckerberg, and Bezos can afford to live in a techno-fantasy. Judith Butler can afford to live in a techno-fantasy. Khloe Kardashian — who “had” a baby through a surrogate — can afford to live in a techno-fantasy (her surrogate is a different story).

On this topic, Harrington also makes some interesting observations (using demographic statistics well) about a sea change in the realm of the “influencer” class. Women, some women, have come to achieve a kind of dominance in some very influential jobs, professions, and vocations. (Four of the five CEOs among the top five American “defense” contractors are now women. You go, girl!) This has been a consequence of what Harrington calls the victory of “freedom” feminism over “interdependence” feminism, a victory which positioned its greatest beneficiaries to become part of what Harrington calls “the cyborg theocracy.”

Musk, Zuckerberg, and Bezos are at the pinnacle of the cyborg hierarchy, but members of the “influencer class” are their ideological non-commissioned officer corps— the people who “make the ideology happen.” Some call them “civil society” — the professions, corporations, non-governmental organizations (the non-profit industrial complex), media, and academics. They’re high-status and well-paid. Which is not to say that they’re all mercenaries . . . many of them are true believers. They really believe their own bullshit, and so they take on the aspect of evangelists. Harrington calls them “meat-Lego priestesses,” the clergywomen of “the cyborg theocracy.”

[I]institutions that set and manage social and cultural norms — such as education, media, law and HR — are all increasingly female dominated. Female law students outnumber males two to one. Women outnumber men in journalism. Seventy-five percent of non-profit workers in the United States are female, and the UK proportion is nearly as high, at 68 percent.

Such workers are chiefly graduates, notably from the arts and social sciences — subjects where women outnumber men two to one in the UK and which lean strongly toward a progressive worldview. And if the disproportionately female graduates of disproportionately progressive elite liberal arts courses, who then disproportionately make up the non-profit sector, have seized enthusiastically on a set of moral [sic] principles and institutional changes that downplay the role of biological sex in a way that benefits elite women overall, so a second key terrain for the contest over the political salience of sex dimporphism is corporate HR . . .

. . . And if elite progressive graduate women are in charge of shaping public morals via non-profits and HR departments, they’re also busy doing so for the next generation in schools: here, too, 85 percent of UK primary school teachers are women, and around 65 percent of secondary school teachers. In the United States. 76 percent of school teachers are women. (pp. 151–2)

As with all the ideologues of progress, and now of emergent trans-humanism, their attacks are leveled against transcendence, traditions, relationships, and reality. Just as nature is philosophically disassembled into “resources,” as a precondition for market exploitation, traditional relations, rooted in some transcendent ground and enlivened through complementary proportionality, has to be destroyed in the great leveling. One of Harrington’s subtitles is “War on Relationships.” (As an editorial note, the war on relationships is ultimately a war on meaning . . . and now, it seems, meaning’s replacement by Dawkins’s memes.)

The relationship she specifically highlights is marriage. Her exposition takes two parallel tracks, finally bending to convergence in what she’d call a “ghost book.” One track is a critique of “erotic individualism” — an anti-marriage tendency on the left and among some strains of liberal and radical feminism — and the other track is a jeremiad against “Big Romance.”

Erotic individualism is the notion that sex is somehow morally trivial and yet still physically exciting and fulfilling. It’s a celebration of the sexual objectification of others, and by extension — as we see clearly now —the objectification of oneself. This was once a kind of flag of emancipation flown by feminists calling for “the zipless fuck,” but it’s come clearly into view now as the shabby ethos of hookup culture, porn, and prostitution apologists. This tendency is anti-marriage on two accounts. Marriage restricts one’s erotic variety (and autonomy), and marriage is just another oppressive vestige of undifferentiated “patriarchy.” Harrington exposes this as just more market ideology, shared paradoxically (or not) by some anti-feminists.

If everyone is economically independent, and sex needn’t result in babies, and none of us needs to rely on anyone else at all, why would any young, heterosexual woman get married? Some simply argue that we shouldn’t: a stance held today across both feminist and anti-feminist [incel, e.g.] sides, where solidarity between the sexes is routinely treated as a bad faith cover for exploitation and reframed in transactional terms. In 2008, for example, the feminist Sheila Jeffreys argued that marriage is a form of prostitution. It’s a view shared by the pro-porn, anti-feminist activist Jerry Barnett, who characterizes graduate women who marry high-earning men as ‘switching some of their corporate earnings for sex trade earnings’. (p. 86)

The problem, of course, for Jeffreys and Barnett and their ilk, is that there are still very many married people (this reviewer included) who know from first hand experience that this is total horse shit. While marriage is never a bed of roses (kind of like life, get over it), it is actually, for many, far better than being single, for the partners and for the children (children are seldom mentioned by people like Jeffreys and Barnett).

The siren call of atomisation comes from everywhere, and legitimates itself in many ways: girl-power self-actualisation and embittered men’s rights activism. for example, are mirroring ideologies driving the same decline into loneliness and mutual hostility. (p. 178)

Marriage can actually be a freeing limitation, like a solid shelter in a stormy climate. It is not, on the other hand, a venue for for “self fulfillment,” the sly promise of Big Romance. When it is entered into with this expectation, it will, by and by, go down in flames. Two self-centered people does not a good marriage make.

Marriage is not a romantic film. It’s a working relationship. Yes, Harrington says, there can and should be affection and erotic attachment as components of the whole relation; but marriage is a partnership in the complementary management of a household, which more often than not — at some stage — includes children. Children can be objects of sentimental affection. But if the day-to-day logistics of raising children that occupies parents’ time and effort (considerable effort, frequent inconvenience, and constant vigilance) are ignored, no child will long survive. The same is true of marriage. Marriage is not, by and large, fun. The only people who still believe that life or marriage are laissez les bons temps rouler are children . . . or technologically infantilized adults. Unfortunately, where I live, at least, this is the majority of everyone from Baby Boomers to the present. We Boomers were the first generation to be technologically infantilized (it took the Army to knock it out of me).

Harrington suggests that the ever higher failure rate of marriage — and I could not agree more — has something to do with self-centeredness inhering within the aspiration for self-fulfillment. The real positive of marriage — which is punctuated by drudgery, hard times, emergencies, and illness more often than “fun” — especially for women , is that “married family units [are] the smallest possible commons outside the market.” (p. 178) It’s the one place where “from each according to his/her ability, to each according to his/her need” still counts. This can be satisfying, even essential, in a philosophical sense, but it’s seldom fun.

(Home, too, is being ever more marketized — think juvie birthday parties at Chucky fucking Cheese.)

Far better [than marriage — Harrington is employing a bit of prosopopoeia here] to deregulate relations between the sexes altogether, and let everyone embrace market forces as they see fit. And whether it serves to legitimise abandoning relationships that don’t measure up to the ‘self-expressive’ gold standard, or as a cynical foil for calls to marketise still further, Big Romance is centrally implicated in this dynamic. (pp. 178–9)

She is not denying, just to get out in front of the predictable liberal reflex, that bad marriages exist, characterized by abuse and violence; nor is she saying that women, or men, should remain in these abusive and even dangerous situations. She’s saying this is not the norm, especially when people go into marriage based on mature reflection and calculation. The best way to find oneself (me speaking now) in a precarious or hazardous relation is to base one’s choices on superficiality, like “looks” (the worst predictor of character there is). The first thing I’d teach my granddaughters to memorize prior to choosing a partner is, if he behaves badly, no matter how nice he looks, “No, he is not going to change. What you see is what you get.”

“Ghost Books” is the title of her Afterword, in which she speculates about future books that she had to exclude in the interest of clarity and brevity as long digressions in this one. She lists three of these ghost books — one on tech, consumerism, and bio-libertarianism; one on the epistemic transitions ramifying out of the shift from print to digital publication; and one asking Lenin’s perennial question, “What is to be done?” The ghost book this reader senses is, “How do we make marriage — as both tradition and counter-culture of resistance — work?” (I’m sure there’s a shorter title out there.)

If feminism is understood as seeing from the standpoint of women and advocating for women’s interests, then Harrington makes a very feminist point about marriage, from the perspective of care-feminism as opposed to self-feminism. Marriage can be and often is a good thing for women. It’s good for men, too; but it affords advantages and rewards that are particularly suited to women.

Her premise, which shouldn’t be controversial, but has become so in the cloud-cuckoo land of cyborg postmodernity, is twofold: (1) there are such things a men and women, discernible by anatomy and physiology, prior to anyone’s perception and acceptance of them, and (2) men and women are different, and not just from the neck down. (I myself was once one of the perversely pig-headed deniers of the latter.)

A third postulate might be, this difference is not pure social-construction, but that leads us into the abstract quicksand of the nature-nurture nonsense again. Better to say — speaking for myself — this difference persists transhistorically, even if it takes many forms, originally (and still) on one account because women can and do get pregnant, give birth, and nurse. Bio-technocracy might have made substantial changes in this for women in the industrialized late-metropoli; but this is still the reality, and will continue to be the reality, for most women in the world. Another difference that persists across time and space is that women generally are smaller and physically more vulnerable than men, and more vulnerable to men.

My wife was very frank with me when we decided to get married. She worked in an environment with a lot of men, aggressive men on an Army post. She told me straight out, it would be immediately better for her in that environment to wear the ring and tell people she was married. If I were using that against her, say, demanding sexual access in exchange for protection and support, then this would look like a protection racket. But while a socially protective function might be discernible, it was not and is not the defining characteristic of our marriage. Nonetheless, this was an advantage for her, as a woman, that was not applicable to me, as a man.

Women raising children alone are faced with far more challenges than women in similar circumstances with husbands. Before the exception reflex kicks in, obviously there are partnerships that are destructive to the point that the single-mom and the kids are better off without the live-in dad. Sometimes, the same applies to single-dads. But, by and large, both women and children benefit in the home and life generally when there is a responsible, respectful husband and dad on board.

Men quite obviously can navigate the world single more easily than women; and men can evade the consequences, say, of their own promiscuity more easily than women. Harrington also gives evidence, speaking directly now of sex, that men are more easily satisfied in casual encounters than women. One statistic she cites, which may not support men’s feverish fantasies, is that women, even promiscuous women, experience orgasms during casual hookups only around one out of every ten times. (Yeah, guys, they faked it.) Christine Emba has written a very good book, cited below, on how often women “consent” to casual sex when they really don’t want to. This has gotten even worse as more men, trained by pornography, insist on painful, degrading, and sometimes dangerous acts with partners that they’d watched and whacked off to in front of their computers. So much for sexual “liberation.”

Her chapter on “Rewilding Sex” addresses this in a distinctively Catholic way. (Read the book and find out.) There is an kind of theological undercurrent to the book; but Harrington has been coy about her own faith — which I sense is there. In the same way that Illich published his seventies pamphlets without naming his Christian presumptions in order to reach a wider audience, I suspect Harrington does the same. As someone whose engaged with the Catholic thinkers Illich and Virilio — as she has, and has said so —I’ve peeked into her playbook.

Christians who haven’t yet subordinated Christ to modernity, nation, or some transient political agenda, will find much to agree with in this work. And like her, I drank a lot of Kool-aid before molting into my present form. Mary Harrington is more than a public intellectual. She’s a witness. She went there and came out again. She has a report.

I’ve gone on long enough. Let’s wrap.

Three recent books from women close to Mary Harrington will make good companion reads. What Do Men Want? by Nina Power. The Case Against the Sexual Revolution, by Louise Perry. And Rethinking Sex, by Christine Emba.

An excellent older, companion read with Feminism Against Progress, especially for an American historical perspective, is Conceiving Parenthood — American Protestantism and the Spirit of Reproduction, by Amy Laura Hall. Dr. Hall gives an incisive, entertaining, and illuminating account of the history of progress ideology in the US pertaining to the ideas and ideals of twentieth- and early twenty-first century parenthood that traces the development of what Mary Harrington calls “meat-Lego gnosticism” to well before the digital age and the emergence of gender ideology as an academic dogma. Hall details the popularity of eugenics among Western (and especially American) liberals until Hitler took it too seriously and the world was confronted with the eugenics end-game — forcing eugenics discourse back into a voluntaristic framework. Where Hall and Harrington converge is around the fact that, while eugenics was banned (and is now making its comeback) from public policy, it’s now being practiced widely in its privatized form. “Family planning” is such a common phrase and idea that it’s now beyond question. Iceland has celebrated the elimination of Down’s syndrome using selective abortion (and euthanasia is now routinely justified in liberal discourse).

Finally, I recommend another older companion book, Disembodying Women, by Barbara Duden, a close friend of Ivan Illich (he died at her home). In 1993, Duden did this deep historical dive into the role of technology in the transformation of pregnancy into a technocratically-managed process of risk management and its epistemic outcomes. Like Illich, she sees herself as an historian of consciousness.

As long as this review is, I’ve really only hinted at the content, insight, and lively writing between the covers of Feminism Against Progress. Since I’ve gone on this long, it’s time to close with the short version: Hell of a good book. Get it.