I’d been studying Ivan Illich, Catholic Theologian, by Colin Miller, when the Promethean socialist periodical Jacobin unexpectedly published two consecutive and somewhat surprising articles. One was by Eastern Orthodox theologian and philosopher David Bentley Hart, called “Christianity was Always for the Poor,” and another by the socialist Director of Operations for Teamsters Local 623, Dustin Guastella, titled “Christianity, Morality, and Socialism.”

Hart has referred to himself as a kind of Tory socialist (like his friend, the British theologian, John Milbank) for some time now, and Guastella has been hectoring his fellow leftists about the fact that the actual working class doesn’t like either liberals or socialists (at Jacobin they are often hard to tell apart) and that the left might do well to abandon their idiotic culture wars if they’re to regain any traction there. (I sometimes count myself as a “provisional subsistence socialist,” just for full disclosure.)

I don’t want to impute any motives to Jacobin’s editorial staff and risk going down an ad hominem side street. Extending the hand to Christians might be principled or instrumental; but as Christians, we need to take it in any case in a charitable spirit of hope and fellowship. By the same token, we need to stay aware and critical. It’s a manipulative world out there.

“See: I send you forth as sheep into the midst of wolves; so be as wise as serpents and as guileless as doves.”

—Matthew 10:16

Time will tell.

You will know them from their fruits.

—Matthew 7:16

When I posted the Guastella article on Facebook, a Facebook friend, Alan Cliffe, himself a declared atheist, replied:

The idea of the current left turning to Christianity to fill in its moral lacunae reminds me of the late-sixties left’s turn to Marxism-Leninism to fill in its theoretical lacunae. It might feel somewhat inevitable when you think about it; this does not mean it’s necessarily the best possible way to go.

Funny how a Christian and an atheist might come to the same provisional conclusions, but from different metaphysical priors and with a different end in view. That said, Hart and Guastella, who may be walking along the same edge of the postliberal conversation, are not the same, whatever Jacobin’s editors may have in mind.

I’m a great fan of David Bentley Hart. I have the first edition of his excellent translation of the New Testament here at hand. The quotes above are from it. He’s a Baltimorean, who writes at times with the cutting wit of fellow Baltimorean H. L. Mencken. Hart is insanely erudite, and, as the article demonstrates, and a lyrically delightful if sometimes demanding writer. My reservations about him—raised by Illich—are minimal, and I want to emphasize something he said in his article to frame the rest of this one.

“There is not,” he points out, “and has never been, a single identifiable thing that we can call ‘Christianity’.” Advocates of grotesque heresies, as well as “secular” opponents of “religion” rely on this generalization for intellectual cover.

“[T]here are many religious phenomena out there,” says Hart, “such as the great mainstream of American white Evangelicalism — to which we apply the word ‘Christianity’ about as meaningfully as we might apply the word “dinosaur” to a sparrow (there have, you see, been a few developments since those days).”

I commend his article to you, because what he says about Jesus (who Christians must learn to re-center), the poor, and the early church, is absolutely true, and as such a necessary corrective to Christians, pseudo-Christians, and non-Christians alike. Hart is a practicing Christian—one, like me, who believes that the Incarnation was and remains real, and not theatrical smoke embroidering some sociological or political performance.

Dustin Guastella, on the other hand, is a somewhat heterodox member of Democratic Socialists of America (and as we said, a trade unionist), who’s been pushing a “left, not woke” agenda for the past several years in the heart of the ever-more-pointless DSA.

His article begins with the cut line: “For some, searching for a surer moral footing upon which to launch a socialist political program [italics added] has again raised the specter of Christian ethics.” Is he being instrumental, yes, but at least he’s out front with it. I, myself, was there back around 2006, when I started, as a communist, to “give Christians a chance.” It’s the beginning of the road, not the end. When I reviewed Abigail Favale’s book, The Genesis of Gender, I wrote:

[I]n her introduction, though, was her description of a “Christian” interlude in which she tried very hard to make Christianity fit together with her earlier political convictions and the underwriting philosophy of those convictions. Mea culpa, I found myself thinking as I read, mea maxima culpa.

Conversions of any sort are a bit like rock climbing. Bring your friction boots and chalk. Everyone needs those handholds and footholds on that precarious psychic rock face of life. Getting from one place to another is a matter of maintaining three points of contact with the rock and reaching for the next hold within range. You don’t let go of one point of contact without locating the next one. Leaping is discouraged, for good reason.

Getting back to Guastella’s Jacobin article, cites Alasdair MacIntyre—a Catholic philosopher, who’s often associated with Charles Taylor as a critic (not enemy) of modernity. In Colin Miller’s long essay on Illich as theologian, he associates MacIntyre with Taylor, Thomas Pfau, and Ivan Illich (and he mentions Stanley Hauerwas). Charles Taylor wrote the long and deeply insightful Foreword to “Rivers North of the Future—The Testament of Ivan Illich,” edited by David Cayley. Just so you get an idea where we’re going here.

MacIntyre fits more easily with Guastella’s own ideological commitments because MacIntyre began his public intellectual career as a Marxist (that handhold thing). And here is where I hold out my foolish hope for Guastella as perhaps a future Christian. He may not yet grasp the full metaphysical consequences of what he has grasped about MacIntyre, but the doors are open now.

MacIntyre’s political legacy has been hotly debated (right-wing communitarian or Marxist wolf in paschal lamb’s clothing?), but the sudden resurgence of his ideas does suggest that the moral hole in the middle of socialism yearns to be filled. Liberalism has no answers. To the question “What is best for me to do, as an individual?” it offers nothing. And when asked “What is best for us to do, as a society?” it simply shrugs. In theory, the former question is meant to be left to the realm of the private, and the latter to democratic deliberation. In practice, however, both are ultimately decided by the market. To surrender moral questions to liberalism, then, is to surrender social questions to the market. And worse, to surrender political opposition to market morality to the opportunists of the reactionary right.

Whether socialism can survive without its bedrock Christian assumptions remains to be seen, but it certainly cannot survive without the working class. And working-class rejection of libertarian responses to crime, social normlessness, drugs, and more has been a stable feature of left-wing political atrophy. In the coming period, socialists will again and again be forced to confront moral questions as social questions. The push for the legalization of more drugs will expand — the State of Oregon at first said yes, and then said no. Sports betting and other forms of digital gambling continue their spread. Next up is whether capitalist societies will liberalize assisted suicide — an option that will surely be taken up by the poor, the disabled, the lonely, the economically “redundant.” What do socialists say? Is it a good society that allows the consequences of its madness to be killed off “consensually”? Does it make one a good person to advocate for it?

Until and unless the Left can develop a consistent moral theory of its own, Christianity will continue to have something useful to say about the biggest social questions that confront modern society. Maybe it’s worth listening. (Guastella)

Hopefully, Guastella will continue with MacIntyre beyond MacIntyre’s 1981 ethical tour de force, After Virtue. Guastella’s not reading a Marxist, but a former Marxist. MacIntyre—like Illich—is a Thomist, and not the shallow reactionary version we see propping up sullen rad-trads with anachronistic proof-texts. (Which is not to say, at all, that tradition is unimportant, it is all-important; but it must be alive and not some dead granite idol.)

I was introduced to MacIntyre during the formative phase of my own conversion by theologian Stanley Hauerwas. He writes in “A Church Capable” (1988) that “faithful living means that we can live confident that God’s victory has been accomplished forever through Jesus of Nazareth.” This, in defense of non-violence, which to many suggests wrongly a total withdrawal from politics, inasmuch as politics presents most often not as deliberation and debate, but as a knock-down-drag-out competition for power. The violence we are seeing now along the fringes of the culture war shows us the shadow if not yet the face of actual war that lies dormant in any society held together by the bonds of bureaucratic management without ethical consensus.

Of course, MacIntyre is not a pacifist, as I am having studied at Hauerwas’s feet as a former career soldier who knows a bit about actual war. Nor are many Christians, who still clutch at the skirts of something called “just war theory”—an idea that’s categorically impossible to implement in any actual war. War can’t be compartmentalized that way.

“What [some] have failed to understand,” goes on Hauerwas, “is that you simply cannot mix just war and pacifism and have a consistent position . . . just war is not simply a casuistical checklist [‘any just resort to coercive force must seek the restoration of peace with justice, refrain from directly attacking non-combatants, and avoid causing more harm than good’] to determine when violence might be used; it is a theory of statecraft.” (Casuistry is “a resolving of specific cases of conscience, duty, or conduct through interpretation of ethical principles or religious doctrine.”) The ethos of Jesus, Hauerwas reminds us, is love of neighbor, and the “crucial test case for such love is love of the enemy-neighbor.”

As an advocate for Christian nonviolence, I am by no means in the majority, even and especially in my Catholic confession, and I don’t employ it as some sectarian litmus test. Even when tabling, however, this fraught question for a moment, what Hauerwas is getting at from “behind the lines,” so to speak, is the perennial temptation of Constantinianism for the church—the alignment of church with power, of altar with throne. Church, for Hauerwas, is meant to be an outpost or embassy of the Kingdom of God in the world, a Kingdom where war and power have been overthrown (“It is accomplished.”) The church’s job is not aligning itself with “secular” power in its many, corruptible, and ultimately vain attempts to “make history come out right.” The Gospel is fundamentally, radically betrayed when the church does this.

If you study those principles of just war, very roughly summarized above, you see in them what MacIntyre, as a Thomist, denounces (and which St. Thomas contradicted himself), and that’s utilitarian consequentialism. And it cannot be otherwise, because war, and even the power prior to war that war serves to guard and extend, is inescapably and amorally consequentialist, even when employed for a “just cause,” like the abolition of slavery.

Abolitionist William R. Williams, writing in 1863 for The Liberator, composed what can be seen now as an apology for total war, shifting the rationale for “just war” from a consideration of legitimate need (e.g., self defense) and proportionality (e.g., minimum necessary force) to a utilitarian calculus that justified the means by the nobility of the cause for which the war was fought. As the blood sacrifices of the American Civil War mounted inconceivably, ending slavery became that redemptive rationale. Williams wrote:

Since the object of a just war is to suppress injustice and compel justice, we have a right to put in practice against our enemy every measure that will tend to weaken or disable him from maintaining his injustice. To this end, we are at liberty to choose any and all such methods as we may deem most efficacious. (italics added)

Constantianism is about more than war, though. War is just one—admittedly the most decisive, destructive, unpredictable, and morally degrading—method of employing power to secure an imaginary foothold in the future.

Constantinianism can come from right, left, or center, depending on which feverish vision one holds of that “man-eating idol” (what Ivan Illich called the future). How to “make history come out right” is always governed by one or another idea of where history ought to go. That can go as wrong with left Constantinianism as it can with right Constantianism. Not wrong in what it does to the world—which is broken and under the authority of the rebellious powers in any case until the parousia—but wrong in the church.

“The Way,” or following Christ, is non-resistant and non-violent. It certainly calls for telling the truth, but that same truth is betrayed when we try to enforce it. The victory of Christ was accomplished on the cross after having told Peter to lay down his sword. As Hauerwas is fond of saying, “Never think that you need to protect God. Because anytime you think you need to protect God, you can be sure that you are worshiping an idol.”

One of the faithful quotes from Tolkein’s Lord of the Rings (yes, a very warlike story) that made it into the films was Frodo telling Boromir—who wants the ring of power to do good (“to defend my people”)—is, “I know what you would say. And it would seem like wisdom but for the warning in my heart.”

A warning bell rings in my own heart upon seeing Jacobin—named after a violent, sectarian faction in late eighteenth century France, manned mostly by bourgeois and and petite bourgeois post-revolutionaries (Robespierre was a lawyer, after all)—making overtures to Christians. The dove says take the hand, the serpent says keep your eye on his other hand.

While David Bentley Hart would certainly exhort other Christians to follow Christ, in this piece for Jacobin he tailors his message socio-politically; and Guastella shows no awareness at all of the centrality—for Christians—of the person and example of Jesus of Nazareth, as the son of God, or of the meaning of the Incarnation. And the danger is not to Jacobin and its readers—I hope it opens a door for them. The danger is in making Christian socialists (as I myself might be counted) who become socialists first and Christians in the service of social-ism (that ism makes it an idol), instead of Christians who contingently advocate for “socialist” measures as a minor way of promoting peace and mitigating mischief.

The same could be said of dispensationalist heretics promoting Americanism with Jesus transformed into a tribal war deity, or of Catholic rad-trads and integralists pining for the re-unification of throne and altar. Like Guastella, they want “religion” in the service of power (or “order”) as a cultural brake on the libido dominandi. They want church to augment the juridical—a performance not of communion, doxology, and liturgy, but of statecraft.

Here’s where Illich enters the stage.

Illich historicized the liberal order—and by extension illiberal modernities—not as against the church, but as the juridical perversion of it. I said I was re-reading Miller’s exposition of Illichian theology, so here we go. It ties in, because the juridical, Constantinian, power-aligned . . . whatever . . . church didn’t appear as some quantum shift one day, but emerged in a dialectic between church and world.

I’ve not noticed MacIntyre mention Illich, nor Illich MacIntyre, but man would I like to be a fly on the wall if by some magic we could put them into a room together.

Miller writes:

[I]t is becoming increasingly clear that the best way to understand Illich is the way he understood himself—as a Catholic fiercely loyal to the Church and to its traditions, Magisterium, and hierarchy. His basic stance consisted, as he said, of “my faith in Christ the Lord and in his Gospel, my faith in the visible Church as it now exists and in its tradition and magisterium, my faith in the universal authority of the Roman Pontiff and in my bonds of communion with a local church and with its bishop.” As such, important and devastating as his critiques of our world were and are, they remain profoundly subservient, in his thought, to the proclamation of the Gospel and the service of the Church. So, while in his critiques of technology Illich rightly belongs alongside Jacques Ellul, Wendell Berry, and George Grant, his Catholic vision makes him unique. In fact, we’ll see that Illich’s claim is exactly that our modern technocratic and bureaucratic world must be resisted precisely because it makes Catholicism nearly impossible to believe and practice. “All these [modern] horrors,” he noted late in life, “major and ‘minor,’ derive their ontological status from the fact that they are exactly the subversions of what Ellul calls ‘X’ and what I would openly name divine grace.” He saw this subversion as the mysterium iniquitatis at work.

Basic to Illich’s convictions was that God had already given the Church everything that she needed for her life and mission in the usual, unsexy, traditional beliefs, habits, and practices of historic Catholicism. He confessed his views to be entirely, even prosaically, orthodox. In the Incarnation, the Son of God had taken flesh for the salvation of the world and instituted the Church, its hierarchy, sacraments, life of liturgy, and hospitality to the stranger and poor. Mass, confession, adoration, and welcome appear variously throughout Illich’s corpus. Even when he was running the Center for Intercultural Formation in Latin America—a rather untraditional post for a priest—he made sure there was a chapel for daily Mass and adoration, which practices he saw as the heart of the matter. Quotidian Catholicism is for Illich the form of life God gave the Church to fulfill its mission. This once overcame the whole world and called people into union with the Trinity. This is the straightforward heart of the Gospel for Illich, the simple practices of Catholicism, and these made the core of his public priestly ministry. He would spend much of his life arguing that to admit the promises of modern advancements into this core was always to corrupt it.

More specifically, Illich was trained as a priest in Rome at the Gregorian, he proudly said, “of the most traditional and, if you want, obscurantist type.” He means that he had studied Thomas Aquinas informally with his (to-be) lifelong friend Jacques Maritain, and credited Maritain with providing the basic “Thomistic foundations of my entire perceptual mode . . . which has made me intellectually free to move between Hugh of St Victor and Kant, between Schutz—or God knows what strange German—and Freud, or, again, into the world of Islam, without getting dispersed.” At Princeton, after suffering a heart attack, Maritain would entrust a course on Thomas’s De ente et essentia to Illich. Among other significant influences was Hugh of Saint Victor, whom he called “my teacher” and whom he read variously over forty years (entirely in Latin). “For decades a very special affection has tied me to Hugh of St Victor, to whom I feel as grateful as I am to the very best of my still living teachers.” A daily reader of the Breviary, and so a student of the lives of the saints, Illich was particularly fond of Saint Alexis, the fourth century Roman who lived as a beggar, and Hoinacki tells us that Illich regularly “praised the invisibility and holiness of [Alexis’s] secret life.” He also had a great devotion to the Virgin Mary, the “strange girl to whom I have not been able to help having as my ideal since I was a boy.”

Illich was summoned to serve as advisor to the four cardinals tasked with moderating Vatican II. The story of his involvement there largely remains to be told. We do know that to refresh himself after the council he went on retreat and set himself to prayer, meditation, and reading five to twenty books per day, “mostly speculative theology and great literature.” Moreover, in Latin America he was involved in a circle of friends that eventually fostered liberation theology, including the likes of Gutiérrez and Sobrino, though, Illich said, he could not agree with them “on liberation and such stuff.”

Apparently headed for a career at the Vatican, in 1969 Illich withdrew from the public practice of the priesthood, amid growing drama—in part misunderstanding, in part real disagreement—surrounding his opposition to American missionary activity in Mexico. Whatever the details, in spite of being investigated by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith in the late sixties, he was never inhibited from his ministry in any way, much less convicted of heterodoxy. In fact, Pope Paul VI (whom Illich had known in Rome as Cardinal Giovanni Battista) told an ambassador sent from Mexico to “tell Illich to remain steadfast in the manner in which he serves the Church.” Only after deciding that his continued ministry might create scandal that would be harmful to the Church did Illich withdraw from public ministry. Even then he affirmed his continual loyalty to the Church, saying to the pope through the apostolic delegate in Mexico, “I humbly kiss your ring and reaffirm unconditional devotion and faithfulness.”

Illich’s work does not offer any new theology at all. The classical statements of Thomas or Hugh, together with the determinations of the Magisterium, sufficed for him. We get no speculative proposals. His contribution lies, rather, in showing us how to recover the power of what we had but have lost. For Illich, the power of traditional Catholic certainties has been ceded to the certainties of modernity. To these savvy Gospel counterfeits Illich offered a simple response: “No!” In this way he has rightly been called an apophatic theologian: Illich proclaims over and over again that school, medicine, transport, and computers are not the content of the Gospel and in fact distort that content. His works are written, down to the many details, to show exactly how it is distorted. He uses history, but he is not a historicist; he writes genealogies but not to deconstruct. Rather, he is engaged in a sort of conceptual archeology aimed at clarifying basic differences. As a carver creates an image by removing what is not part of it from the block, so Illich clarifies the Gospel by unmasking convincing and understandably credible imposters. That is Illichian apophasis. His charge is that removing such modern contaminants frees us to be struck by the stark shape of Catholicism.

All this helps explain why Illich has been hard to neatly categorize. He did not want to “work for revolution,” much less was he a proponent of liberation theology, as Hartch (sometimes) thinks. Neither is he a liberal, crypto-Protestant, nor Anabaptist, as some of his statements on the relation of the Church and politics, the hierarchy, and institutionalized Christianity, taken alone, might allow. Nor is he a conservative, longing nostalgically for the subordination of women and a return to the Middle Ages, as some have charged. Rather, he is “just” a Catholic—and nearly impossible to categorize otherwise (hence the title of this essay). He takes what the Church gives him—nothing fancy or novel—and sets that against the world.

Against the world. And that included his denunciation of the left-Constantinian “rebel priest who wants to use his collar as an attractive banner in agitation.”

When Illich wrote his idol-blasting pamphlets in the 1970s on the institutional deformations of medicine, schools, transportation, and tools—his theological light still hidden under a bushel basket—he was fêted about the way Žižek is now. But when he wrote Gender in 1983, where his critique of liberal modernity more openly clashed with liberal certainties, there was a shrieking of brakes followed by a loud crash. It wasn’t until Rivers North of the Future came out in 2005 that we finally saw a more systematic treatment of the deeply theological character of all his critiques, even and especially of the church and its central role in the development of modernity as a kind of anti-Christ made possible only by the appearance of Christ himself.

Guastella writes, “Consider, also, the publication and reception of the 2019 book Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World. The author, popular British historian Tom Holland, makes the sweeping claim that virtually all that we understand to be part of the rational, scientific, and progressive worldview — including the very concept of secularism itself — is the direct product of the Christian revolution,” Guastella gets it 40 percent right and 60 percent wrong, because the theology is eclipsed by politics, and especially because he hasn’t read Illich. Guastella celebrates precisely the institutional deformations of the church which Illich summarized in (translated) Latin as “the corruption of the best is the worst.”

“It is blasphemous,” said Illich, “to use the Gospel to prop up any social or political system.” And yet, as an historian, he traced the evolution of this blasphemy back to Constantine and through the church itself.

Illich unpacked his “theology” from the parable of the Samaritan, in which he emphasized the scandal of extending—person to person, body to body—love, beyond the boundaries of ethnic altruism. The point wasn’t helping the abstracted stranger/neighbor in need, but a new and highly personalist ethos of choosing friendship beyond traditional boundaries based on a call. This is tremendously consequential for Illich, and it simultaneously opens a new door for love alongside a new kind of evil that was not possible (the best could be corrupted by the worst). Long excerpt here:

The mood, or ground-tone, of this new state was contrition. It was motivated not by a sense of culpability but rather deep sorrow about my capacity to betray the relationships which I, as a Samartian, have established, and, at the same time, a deep confidence in the forgiveness and mercy of the other. And this forgiveness was not received as the cancellation of a debt but as an expression of love and mutual forebearance in which Christian communities were called to live. This is difficult understand today because the very idea of sin has become both threatening and obscure to contemporary minds. People now tend to understand sin in the light of its “criominalization” by the Church during the High Middle Ages and afterwards . . . it was this criminalization which generated the modern idea of conscience as an inward formation by moral rules and norms. It made possible the isolation and anguish which drive the modern individual, and it also obscured the fact that what the New Testament calls sin is not a moral wrong but a turning away or a falling short. Sin, as the New Testament understands it, is something that is revealed only in the light of its possible forgiveness. To believe in sin, therefore, is to celebrate, as a gift beyond full understanding, the fact that one is being forgiven. Contrition is a sweet glorification of the new relationship which is free, and therefore vulnerable and fragile, but always capable of healing, just as nature was then conceived as always in the process of healing.

But this new relationship, as I have said, was also subject to institutionalization, and that was what happened after the Church achieved official status within the Roman Empire. In the early years of Christianity, it was customary in a Christian household to have an extra mattress, a bit of candle, and some dry bread in case the Lord Jesus should knock on the door in the form of a stranger without a roof—a form of behavior that was utterly foreign to any of the cultures of the Roman Empire. You took in your own, but not someone lost on the street. Then the Emperor Constantine recognized the Church, and Christian bishops acquired the same position in the imperial administration as magistrates, so that when Augustine wrote to a Roman judge about a legal issue, he wrote as a social equal. They also gained the power to establish social corporations. And the first corporations they started were Samaritan corporation which designated certain categories of people as preferred neighbors. For example, the bishops created special houses, financed by the community, that were charged with taking care of people without a home. Such care was no longer the free choice of the householder; it was the task of an institution. It was against the idea that the great Church Father John Chrysostom railed. He was called golden-tongued because of his beautiful rhetoric, an, in one of his sermons, he warned against creating these xenodocheia, literally “houses for foreigners.” By assigning the duty to behave this way to institutions, he said, Christians would lose the habit of reserving a bed and a piece of bread ready in every home, and their households would cease to be Christian homes.

Let me tell you a story I heard from the late Jean Daniélou, when he was already an old man. Daniélou wasa Jesuit and a very learned scriptural and patristic scholar, who had lived in China and baptized people there. One of the converts was so happy that he had been accepted into the Church that he promised to make a pilgrimage from Peking to Rom on foot. This was just before the Second World War. And that pilgrim, when he met Daniélou again in Rome, told him the story of his journey. At first, it was quite easy, he said. In China he only had to identify himself as a pilgrim, someone whose walk as oriented to a sacred place, and he was given food, a handout, and a place to sleep. This changed ab it when he entered the territory of Orthodox Christianity. There they told him to go to the parish house, where a place was free, or to the priest’s house. Then he got to Poland, the first Catholic country, and he found that the Polish Catholics generously gave him money to put himself up in a cheap hotel. It is the glorious Christian and Western idea [these touted by both Hart and Holland as exemplary Christianity, and adopted by socialists —SG] that there would be institutions, preferably not just hotels but special flophouses, available for people who need a place to sleep. In this way the attempt to be open to all who are in need results in the degradation of hospitality and its replacement by caregiving institutions.

A gratuitous and truly free choice had become an ideology and a idealism, and this institutionalization of neighborliness had an increasingly important place in the late Roman Empire. Jumping ahead another 150 years from Augustine’s time, we come to a period when decaying Rome, and other imperial centers, were attracting massive immigration from rural and foreign areas, which made city life dangerous. The Emperors, especially in Byzantium, made decrees expelling those who couldn’t prove they had a home. They gave legitimacy to those decrees by financing institutions which would provide shelter for the homeless. And, if you study the way in which the Church created its economic base in late antiquity, you will see that by taking on this task of creating welfare institutions for the state, the Church was able to establish a legal and moral claim on public funds, and a practically unlimited claim since the task was unlimited.

But as soon as hospitality is transformed into a service, two things have happened at once. First, a completely new way of conceiving the I-Thou relationship has appeared. Nowhere in antique Greece or Rome is there anything like these flophouses for foreigners, or shelters for widows and orphans. Christian Europe is unimaginable without its deep concern about building institutions that take care of different kinds of people in need. So there is no question that the modern service society is an attempt to establish and extend Christian hospitality. [per Holland, again —SG] On the other hand, we have immediately perverted it. The personal freedom to choose who will be my other has been transformed into the use of power and money to provide a service. This not only deprives the idea of neighbor of the quality of freedom implied in the story of the Samaritan. It also creates an impersonal view of how a good society ought to work. It creates need, so-called, for service commodities, needs which can never be satisfied—is there enough health yet, enough education—and therefore a type of suffering completely unknown outside of Western culture with its roots in Christianity.

A modern person finds nothing more irksome, more disgusting than having to leave this pining woman or that suffering man unattended. So, as homo technologicus, we create agencies for that purpose. That is what I call the perversio optima quae est pessima [the perversion of the best is the worst]. I may even be a good Christian and attend to the one who asks, but I still need charitable institutions for those whom I leave unattended. I know that there will never be enough true friend with time on their hands, so let this be done. Create services, and let the ethicists discuss how to distribute their limited productivity.

Now, when I speak about this, people tell me, Yes, we see that there’s a kind of suffering of a new kind of suffering in modern life that results from unsatisfied needs for service, but why do you say it’s a suffering of a new kind, an evil of a new kind? Why do you call it a horror? Because I consider that evil to be a result of an attempt to use power, organization, management, manipulation, and the law to ensure the social presence of something which, by its very nature, cannot be anything else but the free choice of individuals who have accepted the invitation to see in everybody whom they choose the face of Christ.

To go a step further: The vocation, the ability, the empowerment, the invitation to choose freely outside and beyond the horizon of my ethnos what gifts I will give and to whom I will give them is understandable only to one who is willing to be surprised, one who lives within that unimaginable and unpredictable horizon which I call faith. And the perversion of faith is not simply evil. It is something more. It is sin, because sine is the decision to make faith into something that is subject to the power of this world. (Rivers North of the Future, 53-57)

In Charles Taylor’s Introduction to Rivers North of the Future, he writes:

The cross, for Illich, stands for renunciation of power. It foreshadows a unity which is manifest in the world but never belongs to it, a unity always out of the reach of merely instrumental human purposes. The Church exists to discern and celebrate this mystery, rather than to accomplish some social or political end. (p. 7)

One of the great difficulties following Illich (or MacIntyre, Pfau, Hauerwas, and Taylor), is that understanding them requires what Alf Hornborg called a “strenuous epistemological effort.” The deepest sense of common sense (instilled by our institutions, their laws, their tools, and their “radical monopolies” of medicine and education) for the modern/postmodern human is this notion of disinterested, institutionally-mediated Morality. Not moral action, but capital-M Morality. In Ethics in the Conflicts of Modernity, MacIntyre discloses Morality as a thoroughly modern artifact.

It is presented as a set of impersonal rules, entitled to the assent of any rational agent whatsoever, enjoining obedience to such maxims as those that prohibit the taking of innocent life and theft and those that require at least some large degree of truthfulness and at least some measure of altruistic benevolence. (p. 65)

The problem encountered in an enclosed commodity-profit pluralism, governed through impersonal bureaucratic management, is that, having thrown aside “tradition” on behalf of this impersonalism, we no longer have a cultural consensus about when and how to formulate rules and obey them according to this putatively universal formula. This putative Morality becomes a matter of endless contention. Shall we be Kantians or Benthamites? Rousseauists or Rawlsians? What is the governing principle? Categorical imperative or greatest good for the greatest number? (What constitutes the good we are seeking the greatest of?) Can we solve these dilemmas with a simple resort to contract (and ahistorical consent)?

Hauerwas, above, says that just-war theory is inadequate in its appearance as a “a casuistical checklist.” Recall, then, that casuistry is that practice of moral philosophers and ethicists, now put in the service of the professions where the dilemmas created by these various responses (deontological, conequentialist, contractarian, et al) when confronted by a reality that fails to conform to the imaginary universalism of Morality. Illich, above, noted that after the service/needs paradigm has enclosed and destroyed vernacular culture, we need to hire “ethicists [to] discuss how to distribute [services of] limited productivity.”

The ethical catastrophe of overthrowing “tradition” is what has preoccupied MacIntyre since the early 1980s. It apparently hasn’t yet occurred to these “socialists” who suddenly want to discuss the utility of “Christian ethics,” which they see as detachable from the person of Christ or the personalism of the encounter between a passing Samaritan and an injured Jew. Guastello fails to appreciate how these several and incompatible answers to the mystery of Morality are irresolvable when we consider that they are based on thoroughly incommensurable intellectual foundations. Not that socialists want to re-organize professors and corporate ethicists; they claim to want to reorganize society, where things become messier by orders of magnitude.

Ethics professors are actually rewarded for slaving away with their subalterns in search of resolutions for all these ethical quandaries, looking for the alchemical miracle that will finally, somehow, make it all fit together . . . universalized at last. But the public is not the least bit preoccupied with academic ethical quandaries, because they haven’t been schooled in the arcanities of philosophy. They’ve been exposed repeatedly to all of the answers at once and do not recognize their incompatibility.

In this sense, everyday folks are probably closer to the virtue ethicists than many professors. They know, intuitively, that right action and wrong action are not detachable from context, even though they do reflexively fall back on (unacknowledged) ethical-school rationales.

On one of my past jobs (deconstruction, not the academic kind), my colleagues and the interns would frequently conduct debates on the job about the ethical dilemmas represented in last night’s episode of House or Law & Order. None of them had ever heard of deontology or utilitarianism, though, at some point, each and all would make deontological or utilitarian arguments—often in the same breath. Were they displaying prejudices sometimes? Sure. But mostly they were grappling with the very thing that MacIntyre has named again and again since After Virtue.

They had no access to Thomism (and not the shallow reactionary kind). They had no access to Illich. They had no access to (they were all atheists or agnostics) the Incarnation. They were separated from these not only by the lack of exposure and the loss of coherence in the jumble of modern development and bureaucratic pluralism, but by the tools and institutions that had formed them (and me . . . and you) from birth.

When Illich wrote his popular pamphlets, Deschooling Society, Tools for Conviviality, Energy and Equity, and Medical Nemesis, during his “Žižek” years, he intentionally avoided laying out his own theological commitments. He had promised the Vatican—after a bit of a confrontation with them—that he would not speak on behalf of the Church. He’d removed his clerical collar so he could pursue his career in history and social criticism. Nonetheless, the precision of his cuts, so to speak, and his uncanny prescience, grew directly out of those commitments (as well as his fluency in at least seven languages and his breathtaking erudition). The socialists wanted to claim him, the anarchists wanted to claim him, and the emergent environmental movement wanted to claim him. But he was none of those things.

Illich had faced off against the ingrained physical and mental habits carved into us by our tools and institutions. Neither MacIntyre nor Hauerwas, methinks, as virtue ethicists, gives sufficient weight to this relation between tools and habits in their promotion of habit formation as constitutive of character. I’m not doing that lazy thing where you point out what someone hasn’t (or, more polemically, “failed” to say or do) said or done (for all of us, this list is interminable); but I’m saying Illich is a necessary addition to their work precisely because he bears down on this, in spite of the difficulties this opens up. Miller said that Illich overcomes even Marx on “the relation between our material culture and intellectual habits.”

I know that Hauerwas had read some Illich, because when I mentioned Illich during a conversation once with Stanley, he exclaimed, “You’ve read Illich?!” In Stanley’s essay with Richard Bondi, “Memory, Community, and the reasons for Living: Reflections on Suicide and Euthanasia” (1976), they wrote (footnoting Illich): “Christians must rethink our relation to modern medicine. For we have been taught that natural death means the death that occurs when doctors can no longer do anything for us, but it may be that we must be willing to die a good deal earlier. For we may well have accepted in the medical imperative a Promethean desire to control death or extend life that is finally incompatible with our Christian convictions.”

I referred to Jacobin as a Promethean socialist periodical, by which I mean they are what I call “radical technological optimists.” Illich contrasted the Promethean worldview—metaphysically underpinned by scientism—with an “Epimethean” one, Epimetheus being the one who undoes the damage done by his brother, Prometheus. Jacobin’s Prometheanism is certainly pertinent here, but I’m risking a perhaps unnecessary digression, so let me return to the epistemically arduous journey created by our tools and institutions which Illich is attempting to make (and inviting us along).

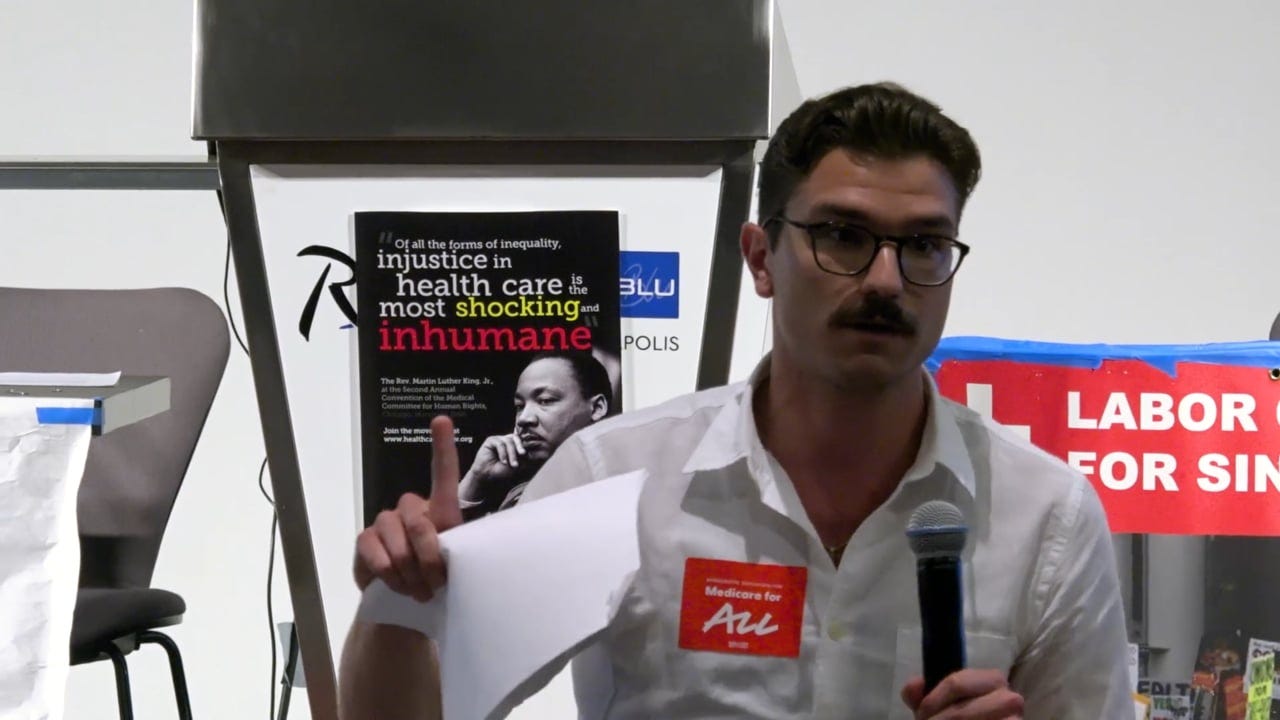

Guastella is a labor activist, and my historical sympathies lean hard in that direction; but at the same time, based on my extended argument about things like the energetic limits to growth, in Mammon’s Ecology (an argument that stands without any recourse to my faith), a lot of labor activism, with its ever diminishing returns, seems—when viewed from above—like the proverbial rearrangement of deck chairs on the Titanic. Illich suggested the same thing in Energy and Equity (which I’d studied prior to penning Mammon’s Ecology).

But even the eco-left—which is keenly aware of how far we’ve passed various points of no return in modernity’s biospheric disruptions—has a hard time with Illichian (or Hauerwasian) Christianity, because even as they’ve exposed the lie of infinite growth, they’ll not soon accept that they can’t “make history come out right” with the proper application of politics. This vain ambition, too, is a modern epistemological artifact, an outgrowth of Bacon’s New Atlantis. Bacon was all about epistemic unmasking—torturing nature like a witch to reveal her magical secrets, in his case—to “build” a new future . . . whereas Illich, MacIntyre, Hauerwas (and a host of others) were and are philosophically bound to something far more contemplative: the receptive participation in what is given . . . that is, the gift.

This is the most challenging epistemic obstacle, or skandal, likewise formed by our tools, institutions, monopolies, built environments, and the ideas and habits they’ve inculcated in us. This “useless” contemplation is our truest access to God, and yet what is most foreclosed in the radical instrumentalism shared by right and left, and by right-Constantinans as well as left-Constantinians in our churches. So many liberal and conservative churches have already fallen into the deep end of Bacon and hereby foreclosed this “useless” sabbatical contemplation except as a form of personal therapy. They want to be “relevant” and to “grow.”

My real concern with Jacobin’s apparent opening to Christians is not that socialists might turn (generically) to Christianity, but that (1) Christians will be pulled further into left-Constantinianism and-or that (2) socialists will fill the ranks of churches as left-Constantinians in the same way that right-wing ex-evangelicals are now carrying reactionary political commitments with them as they flood into the Catholic and Orthodox confessions. Jacobin’s extended hand may foreshadow not greater evangelization of the Gospels but a deepening entrenchment of modernity’s (inevitable) culture wars inside our sanctuaries. Not that I can do anything about it except write and cast a seed that might land on rock or find some small purchase in a scrap of soil where it can pray for rain.

Meanwhile, I can only hope that the church (as “she,” not “it”) can recapture the moral courage to say aloud, that “faithful living means that we can live confident that God’s victory has been accomplished forever through Jesus of Nazareth.”

Great and very timely work! The careful development of some of the ways in which the pitfalls and snares along the true path can sometimes appear beneficial is very instructive. Thank you.