On witches

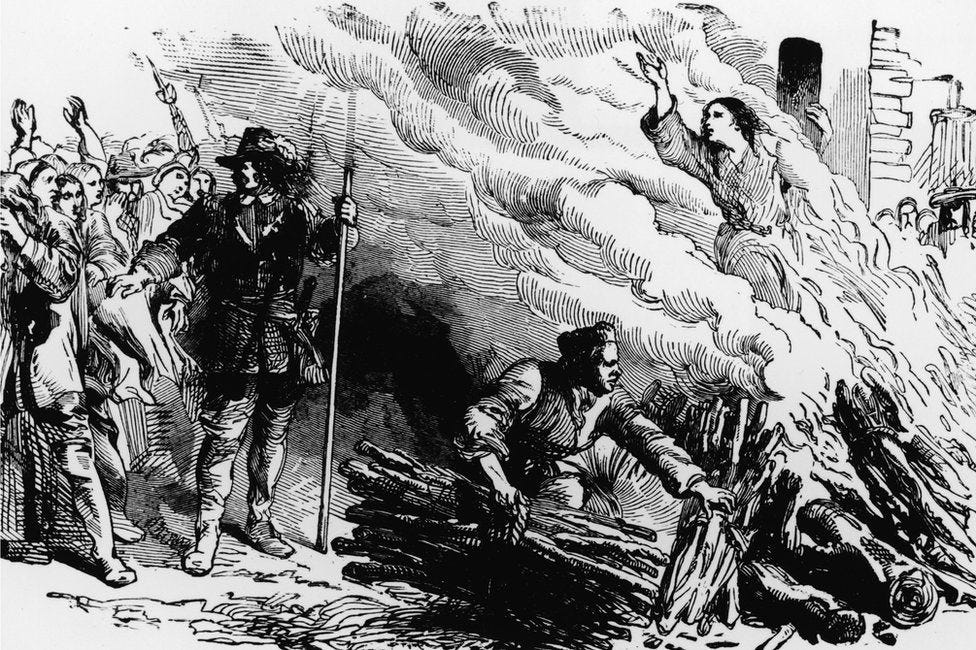

notes from "Borderline"

This post is inspired medievalist historian Lucy Allen Goss’ “We are not the granddaughters of the witches you couldn’t burn: why the myth of ‘lost women’s healing knowledge’ needs to go,” ← strongly recommended. What follows is a somewhat edited version of the section on the witch trials in Borderline—Reflections on War, Sex, and Church (2015).

The Rise of the Lawyers

Wherefore if forgers of money and other evil-doers are forthwith condemned to death by the secular authority, much more reason is there for heretics, as soon as they are convicted of heresy, to be not only excommunicated but even put to death.

—St. Thomas Aquinas

With the New Testament, some very new forms of perception—not only of conception but also of perception—came into the world. I believe that these forms have had a definitive influence on our Western manner of living, shaping our way of thinking about what is good and desirable. I also believe that this influence has been mediated by the Christian Church, which bases its authority on its claim to speak for the New Testament. The Church . . . attempted to safeguard the newness of the Gospel by institutionalizing it, and in this way the newness got corrupted.

—Ivan Illich

In the second quote above, the priest and scholar Ivan Illich, in an interview just prior to his death, was reflecting on what he termed “the criminalization of sin,” the first step down the road to organized violence by Christians.

The church’s later vulnerability to the siren calls of modernity corresponded to the multiplication of hypocrisies by a warlike church. There is little doubt that people themselves were sick to death of wars, and these wars’ association with the church was clear and well understood. This loss of general credibility began with people’s willingness to disbelieve, which had nothing to do with the superiority of a science that was not yet developed, and everything to do with the dissonance between church preaching and practice. The church’s institutionalization under conditions of establishment made this inevitable. The church’s claim to infallibility included the complex development of a comprehensive, self-justifying worldview. Once aspects of that integrated worldview were disproven in part (consider Galileo), the institution reacted defensively. It sought to impose the old “truths” as doctrine, by force if necessary, long after the church’s erroneous claims with regard to “natural science” were publicly viable. This reaction to the church’s epistemological crisis undermined and is still undermining the church’s credibility. This struggle between church and the enlightenment cannot be grasped through some evidentiary debate that sees the sides as antithetical. The enlightenment grew directly out of the church. Illich has made a compelling case that modernity is not the opposite of Christianity, but its deep and demonic perversion.

Rodrigo de Borgia, a.k.a. Pope Alexander VI, was a lawyer. To understand the co-emergence of the enlightenment, the warring nation-state, and witch persecutions, one must also understand the influence of lawyers in a European ruling mindset that was increasingly juridical. Criminalizing sin required the interpretation of law, and this is where Kors and Peters’s assertion that the solidifying ontology of Scholasticism underwrote the witch hunts has merit. It helps explain the rise of the lawyers.

Witch-killing co-evolved with the Enlightenment and shared many of the beliefs and assumptions of the so-called fathers of the Enlightenment. First case in point is Jean Bodin. A Catholic, Bodin is remembered principally as a lawyer and political philosopher. His political philosophy revolved around social order, which was perceived to be in short supply during his life (1530–96). He specifically called for the establishment of powerful central states. He called for dialogue between the various Abrahamic religions, and he placed minimal emphasis on the church as a political actor. He is rightly seen as one of the fathers of the Enlightenment, and yet he shall always be infamous for his enthusiasm for killing (mostly women as) witches. Maria Mies writes,

The persecution of the witches was a manifestation of the rising modern society and not, as is usually believed, a remnant of the irrational “dark” Middle Ages. This is most clearly shown by Jean Bodin, the French theoretician of the new mercantilist economic doctrine. Jean Bodin was the founder of the quantitative theory of money, of the modern concept of sovereignty and of mercantilist populationism. He was a staunch defender of modern rationalism, and was at the same time one of the most vocal proponents of state ordained massacres and tortures of the witches. (Patriarchy and Accumulation on a World Scale, pp. 83-4)

Bodin believed, prefiguring Hobbes and Hegel, in an absolutist state, whose principle responsibilities included supplying human beings for the labor force. He believed that witches and midwives were enemies of the state because, according to Bodin, they caused infertility and performed abortions. He further believed that “witches” taught women birth control, a practice he equated with murder. Bodin wrote a pamphlet against purported witches that was remarkable above all for the cruelty of its recommended punishments for witchcraft. Witches should be prosecuted, according to Jean Bodin, based on the idea that women practicing witchcraft outnumbered men by a ratio of fifty to one.

Bodin sketched out a post-aristocratic society that would be ruled by his own up-and-coming urban mercantile class. The traditional roles of women changed in Bodin’s rationale. Whatever degrading beliefs about women preceded this era, Bodin has introduced a new and utilitarian instrumentality to the proper role of women, that is, as breeders—ergo his paranoia about birth control and abortion. Women are required to produce workers to power the new future being mapped out by Bodin and his contemporaries.

The ancestors of the technocratic nation-state were marked in their origins by the rule of lawyers. Bodin himself practiced law, but in previous periods, the interpretation of law was neither needed nor greatly emphasized in the day-to-day life of most people, whose relations were not juridical. Mies writes that “there is a direct connection between the witch pogroms and the emergence of the professionalization of law.” With the emerging nation-state, Roman law was being adopted to replace Germanic law, and universities were opening law schools to train juris doctors who could effectively manipulate and interpret the complexities of ever more technical law.

Many then were dismayed by the sudden overgrowth of lawyers, complaining that these were lazy, parasitic young men who twisted reason in order to allow the rich to gain at the expense of the poor. There was actually a good deal of truth in this assessment. One cannot help remembering Jesus’s encounters with the scribes, the lawyers of his day, and his rebuke that they had let the letter of the law trump its spirit (Mark 2:27).

One sixteenth-century chronicle stated, “In our times, jurisprudencia smiles at everybody, so that everyone wants to become a doctor in law. Most are attracted to this field of studies out of greed for money and ambition.”

In other words, witch trials were big business. Each one employed a host of judges and lawyers, who competed in verbal puffery with one another to extend and thereby raise the costs (and payouts) of the trial, which even included bills for the alcohol consumed by the soldiers who pursued and captured the suspects.

Witch-trial funds were used to partially finance the Thirty Years’ War.

In discussing the witch trials, we can’t avoid a discussion of the Malleus Maleficarum. This was the notorious witch-hunting guide penned in 1486 by the German priest Heinrich Kramer, a.k.a. Institorius. Jacob Springer is listed as a co-author, but scholars believe his name was added to lend the book credibility. It’s hard to say whether this book was one of the motors of violent misogyny in the emerging Enlightenment, or whether Kramer was a cultural expression of existing popular misogynistic notions and practices. In either case, we can see it now as a tract that actively promotes the idea of witches against the more skeptical voices of the church that had in the past denounced these ideas as popular superstitions. It is not accidental, in my view, that Protestants and Catholics reciprocally demonized one another, and in so doing resuscitated these superstitions; nor does it surprise me that Protestants actually exceeded Catholics in their enthusiasm for killing accused “witches.”

Kramer was a crackpot who stumbled into a niche. Prior to his glory days as an authority on witchcraft, he’d been run out of the province of Tyrol for his near-crazed indictments of several women there as witches. The local bishop called Kramer “a senile old man.” But a Papal Bull had been issued two years prior to the publication of Malleus Maleficarum. Sum Misdesiderantes Affectibus, issued by Pope innocent VIII (1432–92), gave official church recognition to the existence of witches and called on the inquisition (already established) to intervene. When the church assented to the witch-burning craze, Kramer’s book was adopted as the authoritative text on witchcraft. A new invention called a printing press ensured its wide distribution. Between 1487 and 1669, thirty-six editions were published. The “senile old man” became famous on the burnt bodies of women. The title of the book means “the hammer of the witches.” (The word witches translates the Latin maleficarum, which is the feminine form of the noun.) The reason women are more likely to be witches, explains Kramer, is related to the multiple deficiencies inhering in every woman: lust, inability to reason, weakness . . . but mostly lust—crazy horny women.

The purported insatiability of women was nothing new. Men had and have been projecting their own desires onto women for millennia. What was new in this case was the rise of the lawyers.

Some background.

The growth of towns gave rise to the parish church, which became the organizing center of life in these new villages. New religious practices and rituals flourished in these towns, such as local relic veneration, special saints’ days, festivals, and local rules that governed in the name of the church’s idea of hospitality and neighborliness. These practices fit well together in these villages, where most people knew most other people very well and were probably related to them at least by marriage. The greater density of settlement also led to the need for greater administrative control within the population to ensure the peaceful settlement of public concerns and disputes. To accommodate the greater scale of administration, a new juridical idea crept into the thinking of administrators: contract.

Contractarianism, which would come into full flower with Hobbes four centuries hence, germinated in twelfth-century Europe. Seven centuries earlier, the Codex Theodosianus was published (438 Ad) by its name sake, Theodosius, the emperor of Rome. With this comprehensive legal code, for the first time oaths were taken to be legal instruments. Early Christians did not take oaths as a matter of spiritual discipline; they are prohibited in Matt 5:33–37.

The Codex didn’t merely overturn the Christian antipathy for oath-swearing; it made the oath a secular legal instrument, a legal obligation. Most Christians went for centuries afterward never taking an oath of any kind. It was not necessary in the locally self-sufficient ways that peasants managed their lives. But the contract was legally established. So the oath lay in waiting. The newly necessary administrators of the new medieval villages picked it back up. They made it part of a new notion called contract.

Contract disembodies an agreement from its other social contexts and validates it only before the officers of law. The distinction between contract (a modern notion) and covenant (a notion reaching back to the origins of the Hebrews) is that a contract is predicated on suspicion. It places limits on the obligations spelled out, whereas a covenant is based on love or family, and it implies obligations without limit.

The church first adopted the legal notion of contract was regarding marriage, already seen as a covenant in Christian thought. Heretofore, there had been various customs within Christendom for making marriages. Some were parentally arranged, others were assisted by match makers, and so forth. The norms varied, but no one had ever conceived of the idea that the man and the woman making the union would select each other as (temporary) equals before the law. The Roman Catholic Church introduced this idea of a woman consenting as an equal with her own future partner. The first known reference to this legal consent to marriage is in a twelfth century letter from Heloise to Abelard, when she left her religious life to pursue him. A woman was free until she had undertaken the contract, whereupon the conditions of said contract obliged her to obey her husband, and required him to protect and provide for her. The contractual agreement, as Carole Pateman describes it, was for female obedience in exchange for male protection. A grown woman (twelve years old for females; the age of marital consent for males was fourteen) was an agent legally free to submit to this subordinate status with whomever she chose. And as Pateman also points out, husbands had a “sex right” within that contractual relation. It has only been in the last decade or so that we have acknowledged such a thing as marital rape precisely because that “sex right” has been integral, if unnamed, to male-dominant cultural beliefs about relations within marriage, just as that same “sex right” has influenced the modern male idea of an entitlement to sex.

By 1215, when the Fourth Lateran Council was convened by the church, the marriage contract was recognized throughout the church, and women were further confirmed in this newfound portion of legal equality when the same council mandated yearly, private confession “for men and women.” In most places, prior to this practice, confessions had been in public, not exclusively in a private session with the priest.

The contract migrated into the parish system, giving rise to a changed, and far more juridical, outlook on the practices of the church. In this new procedure, God is still necessary, but now as a witness. With time, the citizens of the ever larger and more concentrated cities of Europe increasingly relied on contract. Consequently, the educated urban class came to see society as contractual, prefiguring the idea of a social contract that would accompany the emergence of modernity and the nation-state.

The major sin within marriage was adultery; and as the church had adopted the juridical role of law enforcer in making this new thing—legal marriage—the idea of sin became conflated with the idea of lawbreaking, of crime. Sin had now become crime, placing its resolution not in Christ, and not even before an organic community, but before the administrative authorities. Contract and another new notion, conscience, emerged in relation to one another. Prefiguring Bentham by more than four hundred years, the church used the notion of conscience (an internal forum) as a way of extending its rule-making into the psychic interior of its members, a kind of late-medieval panopticon—a little cop that lived inside your head. Conscience would also become a kind of precondition for the development of the nation-state and its “citizen.”

[Conscience] could be used by the historian to describe an enterprise that was decisively shaped by the Church through the institutionalization of the sacrament of Penance in the twelfth century, an enterprise that since has been followed by other techniques. I would call conscientization all professionally planned and administered rituals that have as their purpose the internalization of a religious or secular ideology. (Illich, Gender, p. 158)

If we want to understand the idea of patria of the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries, the idea of Fatherland, the idea of mother tongue, to which I owe sacred loyalty, the idea of pro patria mori, that I can die for my Fatherland, the idea of citizenship as something to which my conscience obligates me, then we have to understand the appearance of the internal forum [conscience] in the Middle Ages. (Illich, Rivers North of the Future, p. 93)

The Reformation broke over the church with Luther’s theses in 1517. The church was shattered into pieces. The Roman Church found itself in competition for the loyalty of princes and peasants. Between the multiple confessions, the public square had been converted into a competitive marketplace, wherein each faction was branding itself and pitting that brand against an other. In this kind of sectarian devolution, each faction finds it necessary to differentiate itself from the others, and those areas of former agreement are swallowed up in the escalation of both sectarian hostility and opportunistic salesmanship.

In response to this emergency, the Council of Trent was convened between 1545 and 1563. In it, the Roman church referred to itself as a societas perfecta, a perfect society, based in law. The church now prefigures Hobbes’s “contractual” state in Leviathan. Illich says of the council’s self description that it was “a self-understanding . . . reflected in the legal and philosophical thinking of the time, which had begun to portray the state in the same terms, that is, as a perfect society whose citizens internalize the laws and constitution of the state as demands of conscience.”

Basing his Gospel exegesis on the Parable of the Samaritan in Luke 10:25–37, Illich interprets the story to be one where the old boundaries are erased in the new life, where one can see the divine in the face of the other whom one chooses, as the Samaritan chose a wounded and despised foreigner as a friend. In Luke, says Illich, the oaths of the old Testament are combined with a covenant. In the new life, the covenant remains, but the oath as social glue is replaced by the Holy Spirit (not by law) This is consistent, too, with Paul’s epistles.

The rise of the juridical mindset ushered in the power of the lawyers, whom we see in Mies’s account as leaders in systemizing the torture and killing of “witches.” It starts with the Codex, in which oath-taking becomes a legal instrument. With the Codex, the primitive Christian way of enacting its own community—with communion and a shared kiss (the conspiratio, the exchange of the Holy Spirit through the exchange of breath, a kiss on the mouth)—had been overturned. With it went the primacy of highly personal, covenantal relations maintained by scrupulous honesty, which constituted a people whose virtue transcends mere law, a beloved community: “You are not under the law” (Galations 5:18).

Codified law became the new basis of community conformity.

What was formerly categorized as sin was transformed into crime. Church as community was supplanted by church as governor. Church merged with empire, then with states, then it was broken into pieces by the Reformation to compete for state sponsors and popular bases. The state assumed the law, mastered the churches, and reestablished them as dependencies. This, and not “Dark Ages” superstition, was the backdrop for the systematic attack on (mostly) women accused of being witches.

Ontology of the Witch Hunt

A dominant impression in popular Western culture is that witch hunts were a medieval artifact of Western Christianity. Most of us have the idea that witch hunts were the products of superstition, which was swept aside by the Enlightenment certainties of natural science. In fact, the subject of witch persecutions is far more complex, and a little surprising. Alan Kors and ed ward Peters’s book Witchcraft in Europe, 1100–1700 begins with what strikes us as paradoxical:

It seems to us [in]comprehensible that after our alleged period of primitive experience in the West, after our “Dark Ages,” during the centuries of dynamic intellectual experimentation, the renaissance, the Reformation, and, more perplexing still, during that seventeenth century which we continue to consider “the Age of Reason” and “the Age of Scientific Revolution,” Europeans engaged in a systematic and furious assault upon men and women believed to be witches. (pp. 3-4)

Studies show that belief in witchcraft, as a malevolent and efficacious practice, existed in early China, Babylonia, and Egypt. Laws against it were promulgated in these various societies, as well as in pre-Christian Europe and Imperial Rome. Hebrew law forbade all forms of sorcery and divination, though in the context of Hebrew monotheism, these practices were understood less as dangerously efficacious than as idolatrous alienation of affection from the true God. The word translated as “witch” in an infamous translation of a verse from Exodus—“a witch shall not be suffered to live” (Exodus 22:18)—is the Hebrew kashaph, which appears in Strong’s Concordance, and has multiple meanings in its use in the Bible, including “poisoner” and “fortune teller.” Though it is primarily associated with women, the term is used six times in masculine form in the Hebrew Scriptures.

Romans were compulsive record keepers, and one of the earliest in indicators of the popular association of witchcraft with women is an account from 331 BCE, in which 170 women were executed for witchcraft (so much for touchy-feely-witchy paganism). The designated witches were convicted of causing an epidemic. Epidemic was again the catalyst from 182–80 BCE, during which time various Roman authorities put approximately five thousand of these “witches” to death. By the sixth century, somewhat mythologized accounts were written of pagan Vistula River Goth anti-witch campaigns. in the Gothic accounts, witches were exclusively women. There were pre-Christian associations of females with dangerous sorcery in both Germanic and Roman society.

For the first four centuries of Christianity, Christians themselves were emphatically opposed to executing witches. That opposition continued into the time of Charlemagne. The Lombard Code stated, “let nobody presume to kill a foreign serving maid or female servant as a witch, for it is not possible, nor ought to be believed by Christian minds.” The Roman practice of killing women as witches was actually curtailed by increasing Christian influence in Roman society after the Constantinian compact. Between 300 and 700 CE, the church implemented laws against “devil worshiping” and sorcery, but as heresies, and the punishments were generally mild. St. Augustine called witchcraft “illusion, not a crime.” And the First Synod of St. Patrick reads,

A Christian who believes that there is a vampire in the world, that is to say, a witch, is to be anathematized; whoever lays that reputation upon a living being shall not be received into the Church until he revokes with his own voice the crime that he has committed.

In 906, the Vatican declared the belief in witchcraft (in its efficacy) to be heretical. Gratian, writing in the Canon Episcopi in 1140, expressed the belief that Satan was the source of witchcraft and that he had among the people his servants who subscribed to it; but in this case, again, it was the belief in witchcraft that was the work of Satan, which was not to say the “craft” was efficacious. Gratian did, however, lay at women’s feet the “weakness of mind” that opened the door to the heresy, with the claim that women were more likely to believe in witchcraft.

Those are held captive by the devil who, leaving their creator, seek the aid of the devil. And so the Holy Church must be cleansed of this pest. It is also not to be omitted that some wicked women, perverted by the devil, seduced by illusions and phantasms of demons, believe and profess themselves, in the hours of the night, to ride upon certain beasts with Diana, the goddess of pagans, and an innumerable multitude of women, and in the silence of the dead of night to traverse great spaces of the earth. . . . For an innumerable multitude, deceived by this false opinion, believe this to be true, and so believing, wander from the right faith. (emphasis added)

Heresy is a terrible sin for Gratian, to be sure, but he is still clearly calling witchcraft a “false opinion” and denying that these women actually zip through the night skies astride gravity-defying quadrupeds. The Bishop of Worms wrote a long treatise circa 1020, in which he discounted the supposed efficacy of sorcery, witchcraft, and other purported forms of magic.

Christians were, in many respects, the first skeptics.

Sixty years later, Pope Gregory VII beseeched the King of Denmark to end witch-burnings, which were becoming an occasional response to events like crop failure.

Kors and Peters, themselves astonished when their research located witch hunts within the Enlightenment, argue that the outbreak of “witch” persecution actually corresponds to the late development of a formal Scholastic ontology—or beliefs about the nature of being—regarding the devil, which laid down the juridical basis for witch trials.

Before the work of the Scholastic philosophers and systematic theologians in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries . . . the role of the demons in the affairs of man was part of a variegated folklore, and their activities ranged from the horrific and utterly diabolical to a mere impishness and mischievousness, often betraying a whimsical humor. In Aquinas and his contemporaries this folklore became complex and rigorous Church doctrine. The demons . . . were a hierarchically organized army in the service of Satan . . . [who] could tempt human beings into their service . . . the visible agents of diabolical power. Once the witch had come to be understood in this new context, the logic of the witch hunt and execution became manifest and compelling. (pp. 8-9)

in Kors and Peters’s account, the systematic thinking of Scholasticism was a precondition for the juridical mindset of the pre-Enlightenment and Enlightenment, but there is no account of war or misogyny as additional causative factors. While the formal ontology was a late arrival that did be come an important antecedent to the beginning of the “witch” terrorism of the fifteenth through the seventeenth centuries, this ontology was neither the first nor the sole cause of those terrors, even though it served as witch killing’s legal justification.

The church had denounced sorcery and witchcraft centuries prior to the Enlightenment, using the same basic argument that we use today in response to claims of magic and sorcery—that it is illusory. So how did the church, Western Europe, and even the American Colonies, from the fifteenth to the seventeenth centuries, devolve into the orgy of witch persecution that targeted four women for every man?

Let’s zoom in.

The majority of witch persecutions were under civil, not ecclesial, authority. And contrary to many modern impressions, accusations, trials, and witnesses were highly localized. Witch trials were not characteristic of all Europe or even most of Europe. Around twenty-six thousand witches would be put to death in what is now Germany. only four witch burnings seem to have ever taken place in Ireland. The areas that are now Germany and France excelled in the killings. The diversity of the Middle Ages is only infrequently remarked, but Europe was a highly complicated patchwork of communities, customs, and languages at the time. Witch trials and executions were sporadic, local, and frequently caused by mass panics in conjunction with the scapegoating of people (mostly women) who were already unpopular in the community. Personal and inter-familial vendettas as well as naked self-interest [like that of the lawyers] played a role in many accusations.

Women comprised nearly half of all accusers and hostile witnesses in documented cases. Women, like their male contemporaries, and formed by the same customs and narratives, internalized the belief system developed in support of the witch hunts. Structural male power can and does exist without translating into exclusively male initiative and agency. Social control entails the consent of the governed through shared ideas. And some women who made the accusations likely felt their own accusations inoculated them from becoming targets. The participation of women in these outbreaks has multiple explanations, not the least of which is accommodation in various forms to male power.

Three developments contributed to the perversion of the Gospels and led to church participation in “witch” killing, First, the church became the captive of politics and war. Second, the church adopted the surrounding cultures’ mistrust of and contempt for women. Finally, the church went down the path of what Ivan Illich called the institutional “criminalization of sin.” ^^^

The Christian is called to be faithful not to the gods, or to the city’s rules, but to a face, a person; and, consequently, the darkness he allows to enter him by breaking faith acquires a completely new taste. This is the experience of sinfulness. It is an experience of confusion in front of the infinitely good, but it always holds the possibility of sweet tears, which express sorrow and trust in forgiveness. This dimension of the very personal, very intimate failure is changed through criminalization, and through the way in which forgiveness becomes a matter of legal remission of crime, his sorrow and his hope in God’s mercy becomes a secondary issue. His legalization of love opens the individual to new fears. Darkness takes new shapes: the fear of demons, the fear of witches, the fear of magic. And the depth of these fears is also expressed in the new hope in science as the way of banishing this darkness. (Illich, Rivers North of the Future, pp. 93–94).

Ecologies of Power

The fourteenth century brought bubonic plague to Europe. International trade (which facilitated the movement of rats) and urbanization (greater concentration of human populations) acted as the accelerants for the disease. Popular superstitions were inflamed by the experience, and the Romano-Germanic fear of witches was fanned from dying ember to consuming flame in the face of mass death against which there seemed no defense.

The plague dramatically shifted the demographics of Europe, increasing the value of labor and empowering peasants to the point that they began to rebel throughout Europe. The general state of unrest led to accusations and counter-accusations among church officials and political authorities, at a time when corruption had become endemic in the Roman Catholic Church. Nothing was so unpopular among the masses of Europe as the selling of indulgences, coerced bribes given to clergy in exchange for clerical “intervention” to pray dead loved ones out of a twelfth-century Roman Catholic invention: Purgatory. Pope Sixtus IV implemented the indulgence system through a network of collection agents as a new papal revenue stream to pay off Crusade ransoms.

In 1492, the same year in which Isabella and Ferdinand of Spain expelled Muslims and Jews from the Iberian Peninsula and financed Cristobal Colon’s western expedition, Rodrigo de Borgia, a member of the notorious Borgia political clan, took office as Pope Alexander VI. He scandalized Europe with his elaborate political machinations, his accumulation of wealth, his infamous sexual appetites, and his bald-faced nepotism. Alexander rigged the Sacred College of Cardinals by appointing twelve of his own at once, one being his own son. Borgia and his family had great influence on the Vatican by virtue of their enormous wealth. The fast track was prepared for Borgia well before he ascended to the papacy. Trained initially as a Doctor of Law (lawyers again), within three years of his ordination as a priest, this ex-lawyer became a bishop. The long-standing arrangements of church and political authority, sometimes fractious, had shifted into a direct church-political merger in the person of Alexander/Borgia. Popular dissatisfaction had increased to a boiling point when the Pope’s political maneuvering inadvertently sparked a minor war between Franks and Neapolitans. This set off another shockwave of political realignment that in turn resulted in greater social dislocation and popular discontent.

The breakdown of the Reformation and the crises of modernity were and are in many respects based on the structural inconsistencies that preceded the Reformation. The breakdown of Christendom (Christianity in power) was based substantially on the failure of Christians, especially powerful Christian men, to practice what they preached. And that failure can be attributed to the practices necessary for retaining political power.

Brad Gregory writes that “judged on [its] own terms and with respect to the objectives of [its] own leading protagonists, medieval Christendom failed.” In 1517, when Luther published his Ninety-Five Theses, criticisms of the Roman Catholic hierarchy were hungrily received by masses of people who had been thrown into chronic uncertainty by the tectonic political shifts then taking place in Europe. In 1525, Huldrych Zwingli introduced a new liturgy as an alternative to Mass in Zurich. In 1530, Jean Calvin broke with the church and founded yet another theological tradition that would oppose itself to the Roman Catholic Church. The Protestant Reformation had begun.

Small wars erupted, and by 1618 there would be the very big, very complex, and very destructive Thirty Years’ War. Between the Reformation and the Thirty Years’ War, Protestant fought Catholic, Protestant fought Protestant, and even Catholic fought Catholic. These conflicts created an increasingly hateful rhetoric on all sides and the equation of enemies with evil—a kind of vulgar dualism that mapped easily onto the psychic terrain of a Romano-Germanic Europe now in upheaval. This rhetoric increasingly included accusations of devil-alliance and witchcraft. Suspicions of one another, as members of the “legitimate church” or not, transmogrified into accusations of witchcraft; and as in all societies that are placed on a martial footing, suspicion of one’s own people accompanied obsession about the supposed (and sometimes actual) plots of enemy spies. Suspicion is a way of life in wartime; accusations followed.

The church had been aligned with political authority since Constantine, and Theodosius established it as the “official Church of the Roman Empire.” While monasticism resisted “the world,” the church hierarchy, modeling itself on political hierarchies, adapted its practices and doctrine to accommodate the exercise of official (male, it must be noted) power.

Backing up a bit, the example of Jesus—a gentle and pacific Savior, preaching redemption by love—was eclipsed in the beginning of the second century by a growing reaction against the spiritual equality of women in the early Christian view. The emerging church, reflecting the surrounding society, was dominated by men—who appear to have suffered the perennial and world-bound temptation to embrace a masculinity constructed as domination.

Most people would agree that men practice war because men are aggressive; but my own thesis, modeled on Marx’s “inversion of Hegel,” is that the practice of war contributes substantially to the close association of aggression with men—conquest masculinity. The practice is formative of the disposition more than the disposition formative of the practice. Of course, once in motion, this appears as a chicken-egg dilemma.

Whether through exposure to warlike secular rulers before its establishment or through operating within the halls of power after its establishment, the church forgot its early gender subversions and its generally nonviolent character. The gender subversion and nonviolence were forgotten together, because the preparation for and practice of war is and has throughout recorded history nearly always been constitutive of male power, the practice of which is still understood as a high masculine virtue.

Two centuries after the church’s establishment, Emperor Justinian I, a leader who pursued a policy of constant war, appointed its principle bishops. Justinian, in his military attempts to restore the old Roman Empire from his capital in Constantinople, was trying to pick up the pieces of empire that had been chipped away by “barbarian” incursions and political intrigue. Justinian believed that his empire ought to have one, and only one religion; and so the faith was employed instrumentally for political purpose—not unlike today’s “political Christians,” for whom faith serves power as a kind of dike against our libido dominandi.

Justinian, given his soldier’s mindset, sought to “protect the purity of the Church” by executing heretics. The Christian church, which just four centuries earlier had been the victim of persecution by the Roman authorities, now set about the persecution of the internal “other.” That this departure was initiated by a leader immersed in the business of war is not coincidental. Heresy was punishable by death. What the church now had to lose was power. It was Stanley Hauerwas who said, “never think that you need to protect God. Because anytime you think you need to protect God, you can be sure that you are worshiping an idol.” Yet the leaders of the church did not opt, as Christ had, to take the way of the cross. On the contrary, the church adapted to the successor regime of those who had executed Jesus.

There were complex circumstances leading to this phase shift. The church had not, at first, sought power, but rather had fallen into it. For a critical period in history, the church had become the institution with literate people who had administrative experience and the public moral standing to legitimize power. Power had changed hands so many times that “the oldest institution in Western Europe by the eleventh century, self-consciously tracing an uninterrupted history back a thousand years, was the papacy” (Christopher Tyerman, God’s War, p. 4). The church, in its alliance with power since Theodosius, now found itself the most stable political force in Europe, where political borders and rulers were changing with the seasons. The church, in other words, had trapped itself into a kind of political responsibility that was never anticipated by the early church, and one that now forced the militarily powerless church to align itself with shifting politico-military leaderships, choosing in many cases what appeared to be the lesser of several evils. In this way, the church used its own accumulation of power to paradoxically become the servant not of “the least of them,” but of political authorities that themselves proved to be transient.

As authorities shifted and multiplied, the church found itself subject to intrigue, having established itself with bases later divided. By the eleventh century, the Great Schism had separated the Eastern and Western churches, the Western church aligning with the Bishop of Rome against the Bishop of Constantinople, a schism that was temporarily resolved by a protracted adventure which armed the church itself: the Crusades.

By the twelfth century, the horse collar and horseshoe came into broad use in Central Europe, allowing heavy ploughs to work the moist soil. Larger fields were planted farther from home, and agrarians began to concentrate in small villages. These towns became parishes, where local merchants began the process of monetary accumulation that would eventually allow them to usurp the power of the feudal lords. The first steps were taken toward urbanization. This nascent business class would also be drawn into the Reformation as partisans of Protestantism, which would come to preach, against the church doctrines of the past, that the accumulation of wealth is virtuous and that giving alms to the poor encourages sloth.

From 1378 to 1417, there was a schism within the Roman Catholic Church, wherein two different popes were recognized by two competing factions. These destabilizations coincided with various social disruptions. The church had lashed itself to an unstable political ecology, in which the temptation to pragmatism became increasingly irresistible. When witch persecution began in parts of Europe, the church was already accommodating so many practices that are antithetical to the Gospels that embracing the notion of witchcraft, especially as a way of demonizing enemies or terror izing subjects, was as easy as spelling B-O-R-G-I-A. Just add the hatred of women, and stir.

It was during this period of dissolution within the church and of early urbanization that the church established the Inquisition, a loose confederation of church officials who tried people for heresy. Begun in the eleventh century, alongside the First Crusade, the inquisition or inquisitio haereticae pravitatis (inquiry into heretical perversity) was a network of tribunals that rarely practiced torture, acquitted a goodly number of people, and only in frequently used the death penalty (administered not under ecclesial but secular authority). After Justinian, the church had stopped putting people to death for heresy, resuming capital punishment in 1022, six centuries later. This moderation was abandoned in response to the threat of Protestantism, and by the fifteenth century capital punishment had also become a weapon against Jews and Muslims, especially in Spain.

The inquisition was not synonymous with witch persecutions, though approximately five hundred executions were the result of the Inquisition during the period of the witch hunts. Many of these, however, were convictions based on heresy, witchcraft still being seen as a superstition. Even during the witch-craze between 1576 and 1640, more than half of those tried only as witches by Inquisition clerics were acquitted. In 1258, Pope Alexander IV had explicitly forbidden the trial of witches by inquisitors. “The inquisitors, deputed to investigate heresy,” he ruled, “must not intrude into investigations of divination or sorcery without knowledge of manifest heresy involved.”

Pope John XXII reversed the church’s position on witches in 1326, after two attempts on his life, one with poison (associated in the medieval mind with witches). The fear of witches was becoming more widespread throughout Europe and many priests were infected with it, leading them to petition the more cautious Pope for an expansion of the Inquisitorial Charter to include prosecution of witches. The church participated in witch pogroms, in part, because the church had become the captive of politics. It found itself competing for the loyalty of Christians in the wake of war, schism, plague, and reformation, demanding loyalty by force on the one hand and pandering where necessary to popular prejudices and illusions that it had previously rejected. The church’s incoherence in both this practice of persecuting “witches” and attempting to salvage political power was a reflection of this unstable political ecology.

The Crusades (1096–1291) were undertaken in part to unify European Christendom in a time of great political turmoil, and had inured the church to war—including the violent extermination of those accused of heresy. With war comes the logic of war, including “collateral damage” and tactical massacre; and when Christians massacred other Christians who were the cohabitants of Muslim communities, or Catholics who lived among “heretics,” it was seen as tactical necessity. In this period, Christians were already routinely killing Christians, even though in 1054 the Council of Narbonne declared that “no Christian shall kill another Christian, for whoever kills a Christian undoubtedly sheds the blood of Christ.” By the time the church was attacking renegade Christians in the Albigensian Crusade (1209–29), in what’s now southern France, the church was endorsing massacres of heretics. During the massacre of men, women, and children at Beziers in 1209, troops appealed to the abbot with the dilemma that some Catholics lived among the residents, to which the abbot replied, “Kill them all, and God will know his own.”

The hard-heartedness of the practice of war became part of the church’s political language. That this hard-heartedness could so easily be turned against “witches” should be no surprise. By the sixteenth century, Christians were killing Christians throughout Europe in mutually organized warfare. Christians had fully embraced the world’s death-dealing man-sport of war. Those accused of witchcraft were caught in the cultural crossfire.

A major development in the political ecology of the witch-hunt was the development of the juridical mindset, described above as the rise of the lawyers.

Bodies and Objects

Hegel said, “The owl of Minerva spreads its wings only with the falling of dusk,” a poetic assertion that philosophy happens largely “after the fact,” as a reflection on historical events. I’m not sure history bears him out. In fact, philosophy has been part or power’s retinue in many cases, and in key instances, it’s fermented in society’s dough—at first seemingly insignificant, only to bloom into world-historic phase shifts.

Witch hunts combined the aforementioned currents—power, war, misogyny, scapegoating, legal opportunism—but what’s seldom remarked is how they map onto modernity itself through philosophy.

The notion that the world of objects and the world of subjects are separable, in any other than an analytical sense, has been an illusion from the start.

—Alf Hornborg

Incarnation has the Latin word carnis as its root: meat, or flesh. Incarnation, then, means enfleshment, being as a physical body that occupies a specific space and time.

God didn’t become man, he became flesh. I believe . . . in a God who is enfleshed, and who has given the Samaritan, as a being drowned in carnality, the possibility of creating a relationship by which an unknown, chance encounter becomes for him the reason for his existence, as he becomes the reason for the other’s survival—not just in a physical sense, but a deeper sense, as a human being. This is not a spiritual relationship. This is not a fantasy. This is not merely the ritual act which generates a myth. This is an act which prolongs the incarnation. (Illich, Rivers North of the Future, p. 207)

Illich’s focus on embodiment, and consequently on the histories of physical perception, is animated by his concern that modernity and postmodernity have led to the trivialization of the Gospels and the trivialization of the significance of the Incarnation. Illich believed that our epoch is not “secular”— as in the opposite of that other anthropological category, “religious”—but a profound perversion of the Christian Gospels’ “good news.” This disembodiment and a consequent trivialization of Christian belief has some key historical and philosophical turning points. One of them is the work of René Descartes (1596–1650).

in 1987, Susan Bordo wrote The Flight to Objectivity: Essays on Cartesianism and Culture, identifying a key moment in the philosophical development of modernity (and modern male supremacy). Her secular views on the “flight to objectivity” merge, in some respects, with the Christian convictions of Ivan Illich. Bordo is a feminist who has paid particular attention to René Descartes’s philosophy and influence. Her theses contributed to the following observations.

Descartes is associated with something that in philosophical short hand is called simply “Cartesian dualism.” Descartes was a Roman Catholic as well as a mathematician who, interestingly enough, lived in the Dutch Republic, which some regard as the first modern nation-state. His “dualism” is generally cited in works addressed to the philosophically initiated. His ideas—in dough-like fashion ^^^—led to many of our current philosophical, cultural, and even psychological impasses. Descartes is often cited as a “father of science,” and our own time is still dominated in many quarters by a presumption that science holds THE universal key to truth.

(Forgive me, because I’m about to almost criminally oversimplify.)

Descartes led the way in the seventeenth century, establishing an ideal that would endure for centuries: that of the autonomous, self-sufficient, individual philosopher who demonstrates the truth based on reason alone, without relying on anyone else. (Bordo)

^^^ A pertinent observation, this nonetheless does not help the less philosophically initiated get at the core of what Descartes did in a way that illuminates his role in something we will call modern disembodiment. Flight to Objectivity is a meditation on Descartes’s Meditations on First Philosophy, with an eye to that aspect of Descartes and his legacy that is largely ignored—gender, which in turn cannot be dissociated from war. War, ^^^ “religious war,” gave rise in a very direct way to the works of Descartes and of those who followed him into the modern era.

Bordo’s book begins with a discussion of Cartesian anxiety, or Cartesian doubt. Descartes’s philosophical ideas did not appear in an historical vacuum. Descartes’s Meditations were not based on unfounded anxiety. Anxiety based on political instability (as with Hobbes, as well) was characteristic of the age. Seventeenth-century Europe, in addition to reeling from a brutal series of wars, was also a period when medieval cosmological certainties had been overturned by Copernicus and Galileo. The very way of knowing that had prevailed in medieval Christendom was undermined by the astronomical calculations of mathematicians like Descartes and by technologies like the telescope, making this period one of deep epistemological crisis against a background of apparent political chaos.

Using precepts from anthropologist Mary Douglas, Bordo studies how epistemological boundaries were first disestablished then re-established, beginning with Descartes’s origin myth—a nightmare about a cosmic evil genius. This malevolent specter is the original character in the Meditations, which outlines a kind of radical skepticism. Unmoored by the epistemological disruptions of the time, our own senses are just that evil genius, because they make it impossible for a human being to know for sure whether he (Descartes, like all his contemporaries, spoke of men as normative humans) is awake or dreaming, perceiving or hallucinating. Our senses tell us that the sun revolves around the earth, that the earth is bigger than the sun. The senses (read: bodies) are liars, deceivers, the very carriers of madness.

For the whole of my existence—sleeping, wakefulness, internal certitudes, prejudices, beliefs about the external world, feelings, the sense of embodiment—may be the result of a grand demonic deception which we cannot get beyond to determine the true state of things. At each step of the first Meditation, the possible boundaries of illusion widen: at first it is only “certain persons”—the mad—who are victims; then it is every person, but only some of the time; and finally, it is everyone, all of the time, who may be the subjects of a deception so encompassing that there is no conceivable perspective from which to judge its correspondence with reality. The sane may have distance on the mad and the wakeful may, in retrospect, have distance on the dream, but the specter of the evil Genius allows no distance at all. It is a specter of complete entrapment. (Bordo, p. 21)

I remember when I was a child entertaining the fantasy from time to time that I was in a great dream-machine that produced my every perception—that nothing I knew was real, and that I was in the grip of a grand illusion. I doubt I’m alone in having daydreamed about such a thing. Descartes used this fantasy—again, against the backdrop of Europe’s most dislocative epistemological crisis—as the foundation of a new form of knowledge.

Descartes, being a practicing Catholic, retracted from pure, unanchored solipsism by locating a ground in God. God is a guarantor of truth for Descartes, though later philosophers—taking Descartes’s own starting points—will show that God can be sidelined by Descartes’s ideas and eventually set aside altogether (Sartre?). God, for Descartes, is pulled inside the mind where he can do battle with the demon of infinite skepticism. Prior to Descartes, there was no mind—as the opposite of a body—to be pulled inside. There was reason as a faculty, but not a mind-body split. This split is the basis of Descartes’s “dualism,” or two-ness. For Descartes, there was one faculty that could—with proper and godly discipline—hold in check the chaotic deceptions of the body/senses: the dis-embodied mind.

What’s radical about this is not obvious to us today, because modern Westerners have grown up absorbing the premise that mind and the body exist apart in two realms— like interior and exterior.

Prior to Descartes, people assumed a profound connectedness between everything in creation. The cosmos, the soil, children, politics—these were all in some mutually constituting relation to each other. Things fit. If you have an old copy of The Riverside Shakespeare, in the middle of the combined works of the Renaissance bard is a collection of pictures, reproductions of medieval and renaissance art. These are not perspectival art, which begins showing up in Europe during the revival of Euclidean geometry in the fifteenth century. These pictures show ideas—concentric rings of celestial being, great chains that connect the parts of the body to the parts of the political leadership to the parts of the universe, humors, blindfolded women standing on balls before a moon, alongside open-eyed men standing on blocks before the sun, and so forth. These images reflected that infinite complementarity that Ivan Illich describes as “a certainty that there is a correspondence between what is here and what is beyond.”

Bordo points to the emergence of perspectival art, the displacement of meaning by representation, in conjunction with the emergence of Descartes’s ideas. Prior to this era, reason was the counterpoint to corruptible desire, but the idea of a mind-body split was inconceivable in a universe where proportionality, fit, and correspondence mutually constituted all things as a reflection of God’s singular hand in creation. Male and female were understood this way, even if in a hierarchical manner. Heaven and earth were mutually constitutive, with earth being a mother and heaven a father. There was no decisive borderline between complementary realms. Yet, Descartes separates mind from body in just such a decisive way. He calls the two realms res cogitans, the mind, and res externa, the external. In his own time, this was a shattering discontinuity.

For the first time, the self—that is, the mind—is seen as something separate from the world, even one’s own body. For the first time, we are conceived of as living in a permanent state of voyeurism—peering through a window at what is going on outside. We are watchers instead of participants. This is a radical boundary-metaphysic, the mind becoming one person’s lonely bunker. The mind is the subject. All else is object. We are ghosts in a machine. Descartes writes in Meditation V,

For although I am of such a nature that as long as I understand anything very clearly and distinctly, I am naturally impelled to believe it to be true, yet because I am also of such a nature that I cannot have my mind constantly fixed on the same object in order to perceive it clearly, and as I often recollect having formed a past judgment without at the same time properly recollecting the reasons that led me to make it, it may happen meanwhile that other reasons present themselves to me, which would easily cause me to change my opinion, if I were ignorant of the facts of the existence of God, and thus I should have no true and certain knowledge, but only vague and vacillating opinion.

This is one of those cases where one (me, in this case) can agree 99 percent—I get distracted, I have untested preconceptions, I can change my opinion . . . and I do believe that God is the ultimate truth. It’s the segue between (a) changing one’s opinion and (b) belief in God as the sole remedy for all that doubt that exposes this not as an inventory of mental limitations or rational errors, but as an expression of deep existential anxiety. ← Well, God is certainly a remedy for that, but even atheists can acknowledge and overcome or correct mental limitations and rational errors prior to some deep dive into metaphysics . . . or theology.

This state of anxiety, of doubt, is so powerful that objects require our laserlike focus and constant attention. Now you see it; now you don’t. Bordo calls this “epistemological instability.” Descartes was reflecting the social instability caused by the wars of his post-Reformation epoch, and the epistemological crisis caused by Galileo and company.

When [the] world had itself been transformed by Galileo and his colleagues, what had seemed so simple and natural took on the aspect of a mystery. In the new world their renderings of knowledge appeared no longer as statements of a fact, but as posing of a problem. Fresh knowledge made knowledge itself seem impossible in the world it purported to describe. (Randall, Career of Philosophy, quoted in Bordo, Flight to Objectivity, pp. 58–59)

Perceptions were always understood to have the capacity for fallibility, even among the ancient Greeks. But this was something new. A no-man’s land had been established between sense and reality where before there had been intercourse. The self had been driven into a kind of fortification, with all things outside understood as suspicious. This martial episteme had entered decisively into the very heart of metaphysics.

Mary Douglas describes various cultural norms associated with purity and taboos, and she concludes that all societies have psychic demarcations—in fact, no society can be effectively constituted without some notion of outside and inside, of where there is order and what might threaten chaos. I don’t want to deploy a purely psychological critique of Descartes, because while anxiety is understood in the (post)modern mind as primarily a therapeutic issue—something that happens in a the Cartesianized self—epistemological crisis is social. This seventeenth-century epistemological crisis was characterized by terrifying shifts of multiple boundaries; and Descartes was re-inscribing a new internal-external, purity-pollution paradigm to recapture order from chaos. Descartes felt that he needed to re-ground conviction, but to do so he had to invent “the mind” as something that is “inner.” Bordo describes this invention in a chapter titled “The emergence of inwardness.” The fact that we now find this idea of the inward mind so unremarkable is a testament to the broad acceptance of Descartes’s episteme. The dough has risen, the loaf is baked.

in his schema, the problem became “subjectivity.” Subjectivity is a beguiler, a tempter, something for which we ought to be on the lookout, a valid source of anxiety. The mind must be protected from its tendency toward self-deception. Yet, from within this fog of interiority emerges a new kind of vertigo: locatedness. Prior to these developments people understood where they belonged, perceiving in all things proportionality, a fittedness. Personhood was belonging. Practices, narrative orders, and community traditions, as well as intra-community relations and kinship, were determinative of who one was and how one understood oneself. One’s actual, spatial location was a shifting reality secured within this state of belonging. One knew who one was.

Regarding these new crises, Blaise Pascal eloquently described epistemological vertigo:

When I consider the brief span of my life absorbed into an eternity which comes before and after . . . the small space I occupy and which I see swallowed up in the infinite immensity of spaces of which I know nothing and which know nothing of me, I take fright and am amazed to see myself here rather than there: there is no reason for me to be here rather than there, now rather than then.

The telescope and Copernicus’s assertion that the earth was no longer the center of this vastly expanded universe (now conceived of as the “gaping jaws of infinity”) had de-centered human beings and made their actual, physical location at any given time a source of consummate dread. This new existential boundary (inside one’s own head) and this “locational” dread suggested a new kind of fear, one that still haunts us as the loss of meaning. God was no longer the author of a fitted world, but a life preserver in a limitless sea of doubt.

As we shall see, with the assertion of a new form of masculinity, post-Descartes—which I’ll explain below—even this need for God begins to fade into the background. This new scandal of particularity corresponded to the emergence of perspectival space in art. Art now assumes an imaginary (and located) viewer, an interiorized and terrifyingly lonely voyeur gazing out at representations stripped of any meaning. How to resolve such terrible anxiety? Not altogether surprisingly, as a mathematician, Descartes resolved his own doubt with mathematics.

Descartes entertained the idea of some totalizing philosophy, some grand universal theory, that could overcome this doubt, and so he fell upon the idea of something called “pure thought” underwritten by “pure perception,” which we might recognize today as the totalizing truth claims put forward by some on behalf of physical science. Bordo observes,

Such [purified] perception, far from embracing the whole, demands the disentangling of the various objects of knowledge from the whole of things, and beaming a light on the essential separateness of each—its own pure and discrete nature, revealed as it is, free of the “distortions” of subjectivity. Arithmetic and geometry are natural models for the science that will result.

Descartes came to mathematics as a military officer. The inspiration for his philosophical turn came to him while serving as a Bavarian mercenary. The military background here is seldom mentioned except as a curiosity.

This attention to discrete and exteriorized objects—exteriorized from the strategic redoubt, the policed boundary, the military standpoint, mediated (policed) by the purity of numbers—will become the new basis of “knowledge” understood now as “objective.” The ground is now prepared for the totalizing truth claim at the center of a new episteme—eventually, empiricism—as the purifier of understanding. It becomes clear why Bordo titles her book The Flight to Objectivity (emphasis on “to”). objectivity was a refuge for the lonesome, anxious, and decentered self. And here is where Descartes unwittingly opened the door to modern atheism—both metaphysical and practical.

What we are enabled to see . . . is a historical movement away from a transcendent God as the only legitimate object of worship to the establishing of the human intellect as godly, and as appropriately to be revered and submitted to—once “purified” of all that stands in the way of its godliness. Shortly, for modern science, God will indeed become downright superfluous. . . . The godly intellect is on the way to becoming the true deity of the modern era. (Bordo, p. 81)

Descartes opened the door to modernity; but it was others who walked through. His was a conceptual revolution, not yet a methodology. When that methodology was conceptualized, it would be conceptualized as masculine by Francis Bacon and others. Bacon’s “scientist” was explicitly a man (and nature was explicitly female), and latent empiricism brought a new masculinity to the fore: that of the dispassionate fact collector . . . and the witch interrogator.

Bordo’s last chapter is called “The Cartesian Masculinization.” The history of the Cartesian pivot is a step-change in the way masculinity is constructed, even though male social hegemony of various sorts had obtained before, during, and after this transition into modernity. The basis of that dominance undergoes a dramatic transformation, one that was also mapped by Carolyn Merchant as “the death of nature” and by Maria Mies as nature’s co-colonization with women and economic peripheries. Prior to Cartesianism, male and female were undoubtedly understood hierarchically, but they were understood complementarily. The masculine and feminine were understood, as all things were, to be proportionalities, mutually constitutive, fitted, in a world that had not yet been externalized by the fortified self and then atomized into “facts.” Masculinity was conceived as an active agent, and femininity as a receptive agent, with female receptivity understood as a kind of essential fertility and nurturance. God was understood as masculine, and the world—the earth—as feminine. The earth was understood as a maternal presence, as a great mother of all things, living and not, and as such was given reverence.

With regard to nature’s femininity, Merchant points out that ancient mining was considered a kind of midwifing of minerals, which required great spiritual preparation as well as great care in execution.

Minerals and metals ripened in the uterus of the earth Mother, mines were compared to her vagina, and metallurgy was the human hastening of the living metal in the artificial womb of the furnace. . . . Miners offered propitiation to the deities of the soil, performed ceremonial sacrifices, and observed strict cleanliness, sexual abstinence, fasting, before violating the sacredness of the living earth by sinking a mine. (The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology and the Scientific Revolution)

Even in the complex cosmology of medieval Christendom, every particle in the universe was seen as animated by God, pregnant with potentiality. objectivity changed all that.

Karl Stern, a late Jewish convert to Catholicism under the influence of Dorothy Day, born in Germany and naturalized as a Canadian citizen after the Nazi takeover, was a psychiatrist and a neurologist as well as an author. In his book The Flight from Woman, the title of which Bordo intentionally echoes, Stern noted how modernity’s “flight to objectivity” was an attempt to escape the feminine altogether.

If a kind of Cartesian ideal were ever fulfilled, i.e., if the whole of nature were only what can be explained in terms of mathematical relationships—then we would look at the world with a fearful sense of alienation, with that utter loss of reality with which a future schizophrenic child looks at his mother. A machine cannot give birth. (Stern, “Descartes and Gender,” p. 31)

The machine became the metaphor for the objectified universe after the Scientific Revolution. The natural world was understood figuratively as feminine, as is apparent from the writings of Bacon and the other “fathers” of modernity; but female “nature” was not merely subdued. As Merchant notes, it was killed. The pure res extensa came to be understood as a machine, a clock, a collection of matter and energy that was essentially inert. The feminine principle or force was understood prior to Descartes as that of sympathy, relationality, nurturing, a yielding affection. After Descartes, the universe was placed under the control of definition and stripped of its divinity. Purity for Descartes was discrete mathematics which disaggregate the parts of the universe to hold them under scrutiny, the kind of anatomical study that required collections of fact—or a corpse. What had to be purged from the mind to achieve this purity—what was dangerous, as Mary Douglas would say—was sympathy, relationality, an attitude of care or yielding affection. If Cartesian anxiety was a “crisis of parturition,” then the Cartesian revolution was matricide. “For the mechanists,” writes Bordo, “the female world-soul did not die; rather the world is dead. There is nothing to mourn, nothing to lament. . . . The ‘otherness’ of nature is now what allows it to be known.” Bordo calls this de-animation of nature a “reaction-formation.” A component of this reaction-formation, or the “flight from woman,” was the fear of fusion (described variously by Nancy C.M. Hartsock and Jessica Benjamin), the effacement of boundaries between two subjects. Richard Beck, in Unclean—again channeling Mary Douglas—notes that love and disgust exist reciprocally in relation to boundaries, which serve as a kind of policed military perimeter, Beck: “As the self gets symbolically extended so does . . . the primal psychology that monitors the boundary of the body. . . . The boundary of the body is extended to include the other.

The erasure of boundaries, seen as a feminine characteristic (women make new people inside their own bodies, after all), is perceived as a threat by the Cartesian subject, the masculine mind purified by mathematics. The reaction-formation is objectification, a term that has grown so familiar in discussions of sex that it is not routinely associated with its philosophical antecedents in philosophy, that is, subject-object dualism and the notion of object-ivity as antagonist to and remedy for a perilous subjectivity.

Objectification, in a sexual sense, is reducing another person to a sexual object. In war, objectification reduces the other to a dead body. In Descartes, the pure mind is only possible after anatomical dissection, reducing the attentive focus to the discrete parts. Cartesianism is—above all—reductive objectification.

This has a highly gendered genealogy.

Men in some premodern, male-dominant societies believed that women were inherently dangerous. They were bearers of chaos. This corresponds to descriptions of female-nature as capricious or hostile. The Greek deity Chaos, initially genderless, was later portrayed as female. She was goddess of a “formless void,” a kind of pre-existence similar to that described in Genesis. When these ancient ideas were merged with early European Christianity, “fickle” women were portrayed as requiring the headship of men, who ostensibly had the rational faculties required to control women’s dangerous and potentially destabilizing impulses.

When the depredations and dislocations of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries threw the world as it was perceived by dominant men into apparent chaos, women and effeminacy became the cultural scapegoats, as we saw in the accounts of the witch trials that peaked precisely then. Bordo calls the century between 1550 and 1650 “a particularly gynophobic century.” Women accused as witches were specifically accused of engaging in child murder (through abortion and contraception), causing crops to fail, be-witch-ing men, and so forth.

Such fantasies were not limited to a fanatic fringe. Among the scientific set, we find the image of the witch, the willful, wanton virago, projected onto generative nature, whose scientific exploration, as Merchant points out, is metaphorically linked to a witch trial. The “secrets” of nature are imagined as deliberately and slyly “concealed” from the scientist. (Bordo, p. 109)

Francis Bacon referred to matter as “a common harlot . . . [with] an appetite and inclination to dissolve the world and fall back into the old chaos.” Bacon referred to the scientific enterprise in terms that sounded uncannily like torturing confessions out of witches, of “tearing nature open to reveal her secrets”: “I am come in very truth leading to you nature with all her children to bind her to your service and make her your slave.” Bacon, an English Christian—and King James I’s chief lawyer, and an enthusiastic supporter of witch trials—reinterpreted Genesis to support his approach. He claimed that the Fall described in Genesis involved the loss of man’s dominion over nature. He believed that these losses could be recuperated though intellectual effort. As Allen Verhey writes, “To repair the loss of dominion, to reestablish Adam’s dominion, was made one of the objectives of the Royal Society.”

Submission for Bacon and Descartes was still a masculine virtue, but only submission to (masculinized) objectivity, which serves in their cosmos almost like a military superior, giving them direction in the war against subjectivity (the body) and nature (and women). Bacon’s language is not far removed from that of Columbus, who in 1492, writing about his first encounter with indigenous Tainos in the “new” world, said that “with fifty men they can all be subjugated and made to do what is required of them.” The scientific revolution, the witch trials, the extreme gynophobia of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the rise of the nation-state (prefiguring the liberal nation-state), and colonialism were all aspects of the same period and place. This correspondence was analyzed by Maria Mies, who noted the metaphorical conjunction between women, nature, and colonies—all marked for domination by the ascendant, scientific, and moneyed European male. Women were compared to a turbulent and dangerous nature, nature compared to voracious women, and colonies described as effeminate and requiring white, male headship—the danger of the absence of male head ship being . . . social chaos.

Objectivity, control, domination, the suppression of sympathy, and the conquest of the female body (actual or metaphorical) are even today seen as aspects of masculinity, though we treat the Cartesian separations that still dominate our own ideas as if they were un-gendered, when gender was always embedded in gender-neutral language. The essential masculinity of objectivity was assumed. The story of objectivity’s origins in modern “male normativity,” and the corresponding invisibility of women, is then concealed from later generations by gender-neutral language.

Okay, I’ve taken you on a bit of a ride here, and I’m drifting away from “witches,” so I’ll sign off. The point is—sorry for throwoing everything in the pot—is that the witch trials were not what most people thought they were.

Peace.

Word. Didn't think we'd live long enough to have front row seats to this shit. Need to visit before too long. Love you brother. Peace.