DISCLAIMERS: (1) While long, this essay only scratches the surface of the ways in which African Americans and the United States as a whole have grappled over, under, around, and through one another. (2) I will use the shorthand “America” to refer to the United States from time to time (because, among other things, when you go abroad, that is how other refer to us, and because it is common parlance that in no way erases the other states throughout the Americas [which were named after a sketchy Florentine explorer and ships chandler]. (3) The author is not a dispassionate observer, and has a particular theoretical standpoint on these matters.

There are several kinds of American black history, or African American history if you prefer. The pop propaganda version that highlights one or another black paragon from the past as part of, say, Black History Month. Paragon history, whether pop, academic, or quasi-academic is a kind of aspirational commodity. Then there are incident histories and movement histories and period histories and non-hagiographical biographies, which are done by actual historians, some of which I’ll cite below. These are variously inflected by the orientations, objectives, and agendas of the historians themselves; and the several schools of historiography—deconstructive, Marxist, critical historical, comparative, counterfactual, political, meta, micro, prosopographic, sub-disciplinary, and on and on.

Why would I do a long form post on this particular topic?

First of all, it’s important to the moment. A lot of people are saying things right now that collide with “race” history in the US, and they frankly don’t know what the hell they’re talking about. That doesn’t just include negrophobes in the Republican Party. It includes a lot of people who oppose them. So, it’s a small corrective. American black history is American history, woven into every fiber of our national past and present. For the purpose of discussion political strategy (which always entails a struggle of some kind), it may be America’s most salient, and transhistorical, thread (one could say the same thing about Native history, though this “group” is far less homogeneous).

Secondly, black history in the US is not just something I’ve been witness to for seven decades, it’s been an abiding interest for the last three decades, and I have a personal stake in it through family.

Finally, as an old soldier, strategy and tactics (which I taught at the Jungle Operations Training Center in Panama and at the US Military Academy at West Point, and practiced on four continents) have long interested me; and this piece is a way to share my own attempt to merge those historical and strategic interests. I myself am not a trained historian, but an over-the-counter social critic who just happens to be interested enough, graphomaniacal enough, old enough, and retired enough, to spend weeks at a time in my basement office raking through research and memory to fill (often) too many pages with my interpretations.

This monograph will punctuate a 234-year overview with reviews and assessments of political strategies. We can start anywhere, but I’m going to begin with Zora Neale Hurston (1891-1946), heterodox anthropologist and novelist.

She did extensive studies of creole culture, and took a special interest in Haiti. Most people will aim you at her book Mules and Men, but I’m going to recommend Tell My Horse—they’re both books about Haiti. As a companion read, I’ll suggest C.L.R. James’ (1901-1989) The Black Jacobins (1938), a history of the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804), where you can study the strategies of that struggle in great detail.

Why Haiti? you may ask. We could start anywhere, why not with the whole transatlantic slave trade.

Several reasons.

Jean-Jacques Dessalines

First of all, James gives a pretty good account of that trade, before he opens his story on the particular cruelties of the French in Haiti. (They say Dessalines massacred the whites, but he massacred the French and spared the Poles.)

The whip was not always an ordinary cane or woven cord…sometimes it was replaced by a thick thong of cow hide, or by the lianes, a local growth of reeds, supple and pliant like whale bone…The slaves received the whip with more certainty and regularity than they received their food. It was the incentive to work and the guardian for discipline. But there was no ingenuity that fear of a depraved imagination could devise which was not employed to break their spirits and satisfy the lusts and resentment of their owners and guardians.

Irons on the hands and feet, blocks of weed that the slaves had to drag behind them wherever they went, the tin-plate mask designed to prevent the slaves eating sugar cane, the iron collar. Whipping was interrupted in order to pass a piece of hot wood on the buttocks of the victims; salt, pepper, citron, cinders, aloes, and hot ashes were poured on the bleeding wounds. Mutilations were common, limbs, ears, and sometimes the private parts, to deprive them of the pleasure which they could indulge in without expense. Their masters poured burning wax on their arms and hands and shoulders, emptied the boiling sugar over their heads, burned them alive, roasted them on slow fires, filled them with gun power and blew them up with a match (this was called 'to burn a little powder in the ass of a nigger'); buried them up to their necks and smeared their heads with sugar that the flies might devour them, fastened them near to nests of ants or wasps; made then eat their excrement, drink their urine and lick the saliva of other slaves.

This revolution, the only one in modern history that emerged from a slave revolt, came on the heels of the American and French Revolutions; and America’s economy was entirely predicated (even in the North) on Southern slavery. The guy in charge of France at the time was named Bonaparte. You’ve heard of him. Haiti was his richest colony, and it provided much of the wealth to pursue his martial objectives in Europe. (Full disclosure, I am a longstanding Haitiphile, and between 1994 and 2006, I spent a lot of time there, including becoming pretty deeply embroiled in their politics.)

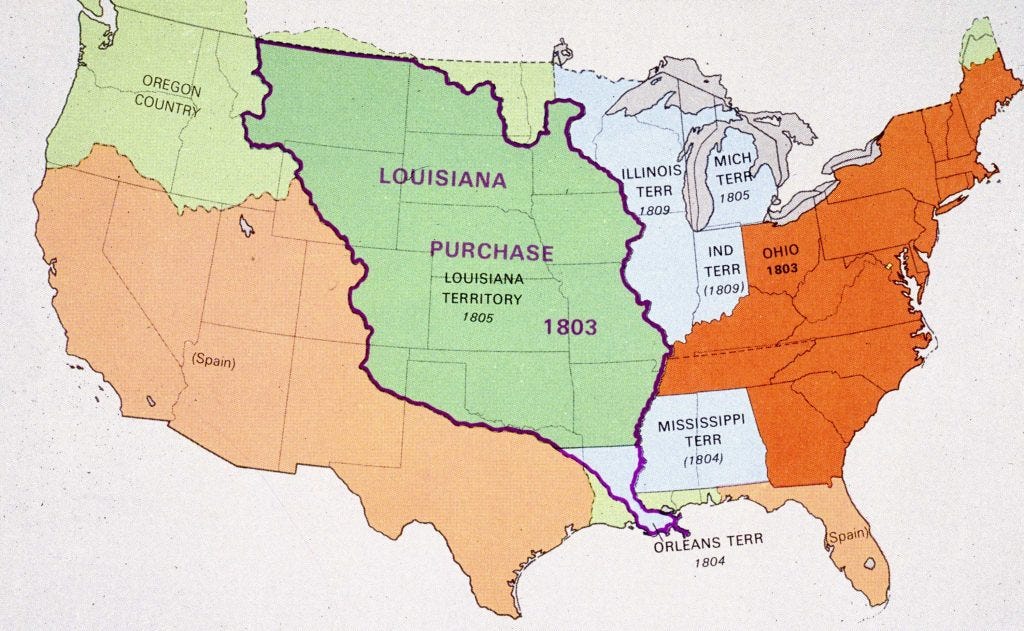

Napoleon was forced to redirect military force to Haiti’s rebellion. It drained his treasury, whereupon he decided to sell a bit of French land to the newly independent Americans. That bit of land was called the Louisiana Purchase. It became most of Montana, more than half of Wyoming, most of North Dakota, all of South Dakota, a big chunk of Minnesota, half of Colorado, a corner of New Mexico, Northern Texas, Oklahoma, Nebraska, Iowa, Missouri, Arkansas, and half of Louisiana. The sale netted Napoleon 60 million francs in cash and 18 million francs in debt forgiveness from the United States.

828,000 square miles of land . . . because of a slave revolt in Haiti.

The revolt in Haiti also scared the living shit out of every slaveholder in the United States. The military defeat of the French (and the Spanish and the English) by a bunch of African slaves shattered the narrative of white supremacy and of black passivity in one fell swoop. This was not great news for American slaves, because the slave owning class began cracking down as never before, dramatically increasing their control measures and their cruelty.

Many Haitians, fleeing the violence in Haiti during and after the Revolution, also ended up in Southern Louisiana, where an 1811 slave revolt was, in fact, inspired by events in Haiti, in an area north of New Orleans called German Coast, led by a biracial slave driver named Charles Deslondes. It took the Army to put the German Coast uprising down.

During the colonial era, there were eight notable conspiracies and rebellions between 1663-1741, and fourteen between independence and the Civil War.

Something I realized while working in Haiti and studying the history of Western capitalist slavery (which differs a good deal, by the way, from classical and “biblical” slavery), was that the United States was already being hemmed in by the abolition movement prior to the Civil War and manumission, and so, American slaveholders were “breeding” new slaves, whereas in Haiti, at the time of the rebellion and revolution, the French simply worked most of their slaves to death and imported fresh ones. Consequently, few American slaves, at manumission, knew their own ancestry. In Haiti, to this day, people can tell you they are Congo or Ibo or Guinea or whatever ethnicity from throughout sub-Saharan Africa. In fact, when you cross the Riviere Massacre between Dajabon in the Dominican Republic and Ouanaminthe in Haiti, it’s very much like leaving Latin America and crossing directly into West Africa in terms of the cultures.

Before progressing through time, it may be a good idea to get a bit more context with regard to what I just called “capitalist” slavery. I mean, there were two capitalist aspects to the trade in human beings: one was the trade itself, with humans as the commodity, and the other was the list of actual goods produced through the exploitation of slave labor, like sugar and sisal in Haiti, for example, or cotton and tobacco in the Colonial and post-independence South.

The first sweetened cup of hot tea to be drunk by an English worker was a significant historical event, because it prefigured the transformation of an entire society, a total remaking of its economic and social basis. We must struggle to understand fully the consequences of that and kindred events for upon them was erected an entirely different conception of the relationship between producers and consumers, of the meaning of work, of the definition of self, of the nature of things.

-Sydney Mintz, Sweetness and Power

I’ll leave a number of reading suggestions as we continue, and I’ll begin by promoting Sydney Mintz (1922-2015) was an “anthropologist of food,” who wrote the book Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History (1986).

Add to that Sven Beckert’s Empire of Cotton: A Global History (2015).

Add to them Clive Ponting’s (1945-2020) World History: A New Perspective (2000), David Etis’ The Rise of African Slavery in the Americas (1999), Eric Williams’ Capitalism and Slavery (1994), and Raj Patel and Jason Moore’s A History of the World in Seven Cheap Things (2017), and you’ll be well on your way.

Why so much on context?

Because African America didn’t just appear on the stage of history like a leprechaun. More importantly, because the history of African America is embedded in the history of capitalism, a connection many—including some historians, even including some African Americans—would like to evade by reducing slavery, Jim Crow, etc., into a purely racial/moral question (race reductionism).

To flesh out your historical accounts, you may want to check out a few things written or transcribed from actual slaves and former slaves: Walter Johnson’s Soul by Soul, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (by Douglass), Stephanie Camp’s collection of oral histories, titled Closer to Freedom: Enslaved Women and Everyday Resistance in the Plantation South, and Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, by Harriet Ann Jacobs.

The next step in contextualization is a review of the causes of the American Civil War. The slave system in the South had been in tension with the industrializing economy of the North since before independence. How is this “black history”? Because it took this incredibly bloody war to settle the question of slavery.

In 1860, the total population of the US was 31,443,321. 3,953,760 (12.5%) of them were black slaves. By the time the war was over, 750,000 Americans were killed (up to 50,000 of them black), and an equal number maimed. Adjusting the ratio to the current US population, that would be 7,622,200 killed. (Perspective)

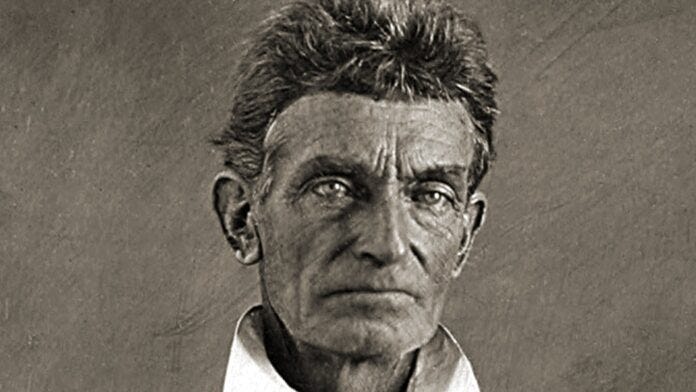

The rivalry began over American expansion. “Free labor” wanted to prevent slavery in the new territories. They wanted the economic opportunities, and these new proto-libertarians saw slavery as undercutting them. The foundation of Lincoln’s Republican Party was the free labor movement, something detailed in Mark Lause’s Free Labor: The Civil War and the Making of an American Working Class (2015). Free laborists natural tactical (if not always ideological) allies were the Abolitionists. (John Brown, for example, was an evangelical Christian and a radical abolitionist.)

People who say the Civil War was about anything except slavery are talking directly out of their asses. It was absolutely, singularly, in all caps, about slavery. Free labor and slaveholders both had a stake in expansion, as potential beneficiaries of capitalist “growth.” It was also an ecological matter, inasmuch as Southern planters were wrecking the soil and coveted the new land. The compromises made in the struggle for independence were ultimately unable to contain this contradiction. As historian Eric Foner said, “The political system had proved incapable of finding a middle ground between an increasingly confident and assertive North and an increasingly defensive and belligerent South.”

“Rise Now and Fly to Arms!”

The Civil War did something more than accomplish a Northern victory and manumission. It recruited black soldiers and gave them combat experience. Sixteen black Union soldiers were awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for bravery.

“Once let the Black man get upon his person the brass letters, U.S.,” wrote Fredrick Douglass, “let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pocket, and there is no power on earth which can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship.”

Armed black people with military equipment and experience were also emboldened in to make demands even on their new employer. Black soldiers (ten percent of the Union Army by the end of the war) mounted a campaign for equal pay with white soldiers, which bore fruit in Congress in 1864, when a bill was passed mandating equal wages.

By the war’s end, almost 200,000 black men had served, around half having been free blacks from the North, and the other half former slaves. 40,000 were lost to the war (like their white counterparts, they suffered three deaths by disease for every one death in battle). Blacks had fought in both the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, but not in these massive numbers.

The first combat action in the US Armed Forces that was directed (not commanded) by a woman was when Underground Railroad conductor Harriet Tubman guided Union forces in the 1863 raid on the Combahee Ferry, that freed more than 800 slaves. Tubman was a scout, and glued to the side of Commander James Montgomery. She also served as an intelligence agent for the Union, and became close friends after the war with Lincoln’s Secretary of State, William Seward.

Black soldiers went into politics, serving in public office, and others remained under arms, during the period of Reconstruction. Black soldiers, in fact, protected the emergent free black communities, which flourished in protected places throughout Reconstruction.

So, what about Reconstruction? Well, without that account, again, you aren’t really doing African American history.

There have been many books published on Reconstruction (1865-1877). I’m just going to throw out three titles: Black Reconstruction in America, by W.E.B. DuBois (1868-1963), and Eric Foner’s Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution. (Both books begin their accounts in the Union Army camps.) Also, Heather Cox Richardson’s much more recent The Death of Reconstruction: Race, Labor, and Politics in the Post-Civil War North yet.

Reconstruction brought many advances, but with them, resentment and a violent backlash. So, what was this thing called Reconstruction? It was the attempt after the war to reintegrate eleven states that had seceded from the Union. This attempt included military occupation and enforced legal reform.

It was in 1868, in state after state, when Black men, many of them formerly enslaved, gathered with white men, many of them poor and disempowered until Reconstruction, to rewrite the constitutions of the South.

—Adam Sanchez

Newton Knight, Confederate deserter, leader of a multiracial guerrilla force in Mississippi

You read that rightly. Black and white, in the South, once worked together . . . politically. The well-known film, The Free State of Jones, was about a coalition of white Southern Unionists and African Americans. This is a facet of American “black history” that’s overlooked by many, especially race-reductionist, historians, ever allergic to the histories of class struggle which simultaneously undermine race-reductionism and let in an unwelcome light on black intra-racial class exploitation and privilege. (For a more detailed exposition of this, see my essay on critical race theory here.)

Black self-organization and activism began within weeks of the end of the war in April 1865. Within the first two years, Equal Rights Leagues were organized throughout the South, not only locally but at the state and regional levels. Lincoln’s Republican Party became, almost overnight, a biracial formation, with the majority of Southern delegates (265 in total) being African American. Sixteen black men were elected to the US House of Representatives. 600 were elected for state legislatures. Black candidate Hiram Revels became the first black US Senator, taking the seat surrendered by Jefferson Davis in 1861. Blanche K. Bruce, a former slave, was also elected to the US Senate by Mississippi in 1875.

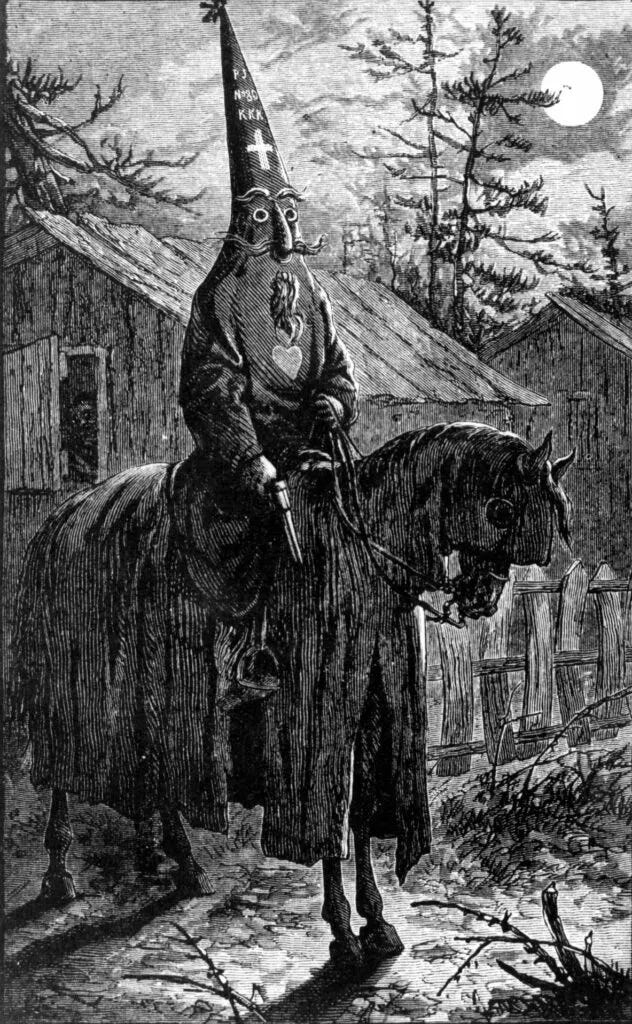

In the background, though, was Lincoln’s tactical choice for the Vice-Presidency, Andrew Johnson—a Southern Democrat. Prior to his assassination, Lincoln was navigating a center-of-the-road “soft” Reconstruction policy that was opposed by resentful Southern whites on the one hand and the radical Republicans, including the new black leadership (who wanted a stricter and more punitive Reconstruction) on the other. When Lincoln was assassinated, Johnson “softened” the terms of Reconstruction even further, pardoning Confederate military leaders, and opening the door for Southern terror militias, like the White League, the Red Shirts, and the Ku Klux Klan—the most significant being the Klan, organized by the pardoned Confederate guerilla leader Nathan Bedford Forrest. The Klan murdered black people, black leaders, and white Republicans during Reconstruction, and terrorized thousands of others with assassinations, rape, public whippings, arson, and lynching.

The political wing of the KKK was The Young Men’s Democratic Organization, organized into local clubs, who would do politics by day, and terrorism by night.

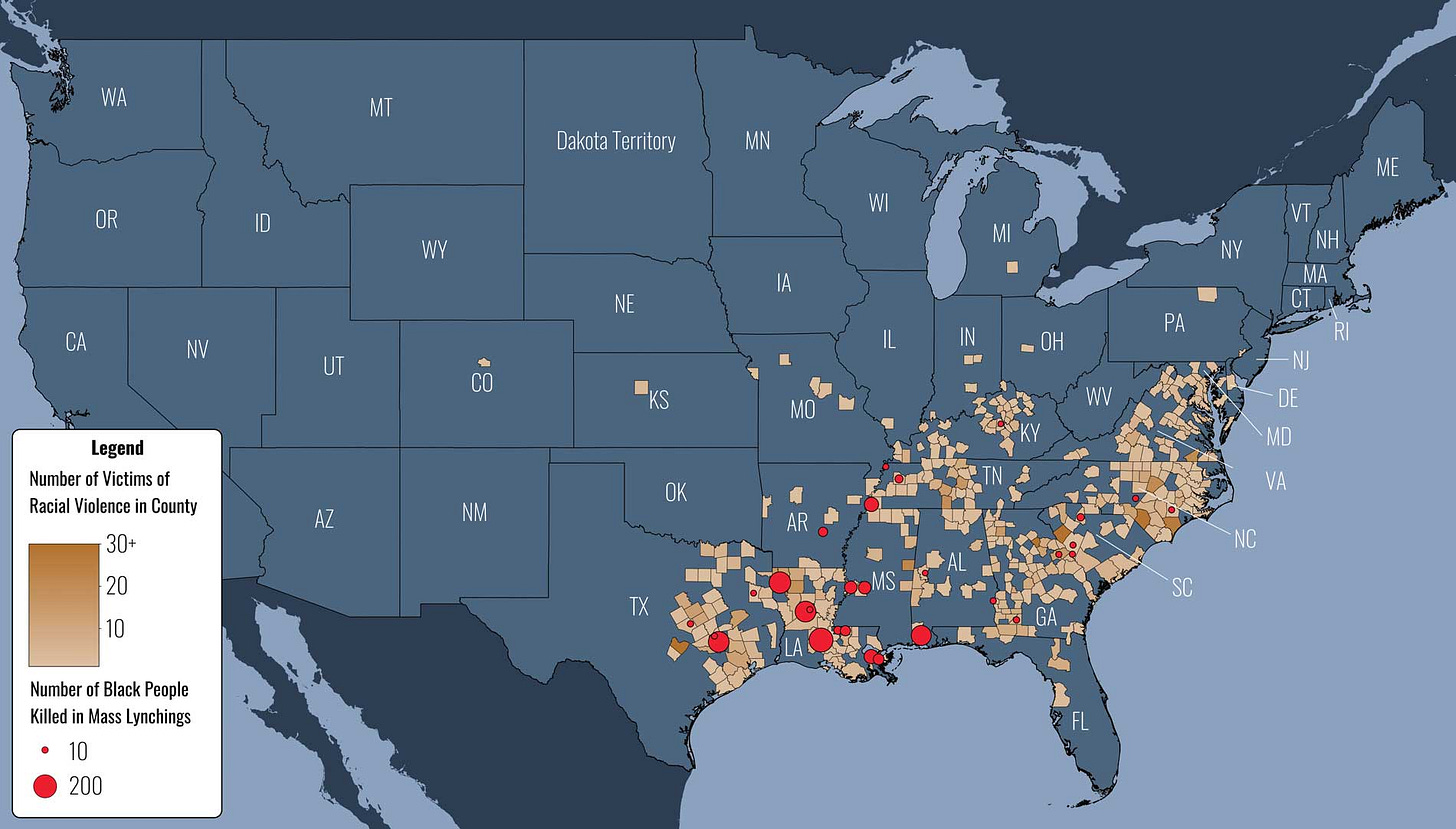

During Reconstruction, there were more than 2,000 lynchings, including 34 mass lynchings. Not one was ever prosecuted.

Whether dealing with slaves or freedmen, southern courts and jurists seldom wavered from the urgent need to solidify white supremacy, ensure proper discipline in blacks, and punish severely those who violated the racial code . . . After their initial experiences with the judicial system, many freedmen found little reason to place any confidence in it. The laws discriminated against them, the courts upheld a double standard of justice, and the police acted as the enforcers.

—Leon Litwack, Been In The Storm So Long: The Aftermath of Slavery

The Klan’s operations first concentrated on Georgia, later spreading throughout the Black Belt, attacking black and white members of the Republican Party (in an historical flip, many of today’s Republicans are the last bastion of white supremacy). In 1868 alone, the Freedman’s Bureau reported 336 cases of murder and attempted murder by the Klan.

Harper’s Weekly pro-Klan cartoon, 1868

For details, read the Equal Justice Initiative’s “Documenting Reconstruction.”

This campaign of terror was strategically aimed at voter suppression to unseat Southern Republicans. By 1871, Georgia was returned to Democratic control. Not without resistance. Black and white Republicans rebuilt burned churches, protected victims, and, with some frequency, shot back.

After the end of Reconstruction in 1877, the Klan dissipated into various decentralized militias and clubs, and would only be revivified (in Atlanta) in 1915. (Registered voter turnout in South Carolina in 1877 was 110 percent, the apocryphal story being that every dead man in the state made it to the polls.)

The “second Klan” took root in 1915, and experienced rapid growth, facilitated by a popular film, The Birth of a Nation (see below).

President Woodrow Wilson was a Klan member, sworn in by a Klan-member judge. Presidents Harding, and Coolidge were all Klan members. Wilson would eventually fall out with the Klan over his appointments of Catholics to public office, not his continued and virulent racism.

At any rate, Reconstruction accomplished three Amendments to the US Constitution the 13th Amendment (1865), which abolished slavery throughout the United States, the 14th Amendment (1868), which guaranteed birthright citizenship and equal protection under the law for all people (one among several that Trump is now trying to violate), and the 15th Amendment (1870), which prohibits denial of the right to vote based on race, color, or previous condition of servitude. But we’ve jumped ahead.

Reconstruction wasn’t “deconstructed” solely by post-Confederate reaction, but also by the weakening of “free labor” support. According to Richardson, the class struggle narrative adopted by freed black workers were what turned Northern free-labor class-accommodationists—Calvinist work-ethic types who adhered to an earlier version of trickle-down/proto-libertarian economics—against Reconstruction. The terrorism unleashed in the South by the Klan and the Black Codes were the hammer, but the hardening of attitudes by Northern free labor against blacks, who failed to fulfill free-laborists’ fantasies of expansion, became the anvil that would finally crush Reconstruction.

There is a prefiguration here of Langston Hughes’ eventual grievance against American communists’ efforts to turn the black working class into a new vanguard; but the difference was that—in spite of communist opportunism in some cases—the American Communist Party, in the early decades of the twentieth century, not only stuck with African Americans, a substantial number of whom themselves joined the party, they were the only leftist formation to do so whole-heartedly . . . a subject we’ll get to in a moment. (See Gerald Horne’s Black and Red: W. E. B. Du Bois and the Afro American Response to the Cold War, 1944–1963.)

The free labor movement regarded the working class—which it did see in class terms, but not class struggle terms—as a kind of industrializing Jeffersonian formation. There’s a long historical side trail here, with regard to the role of the Mexican War in creating the conditions for the Civil War, and the Free Soil Party—motto, Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men—but we’ll summarize.

“Northerners entwined their ideas about African-Americans with their hopes and fears for the country as a whole. Northern attitudes toward freedpeople became part of the general anxiety over the national government, which had grown so dramatically during the Civil War and which continued to grow in Northerners' imaginations even more quickly than it did in real life. The impressions they formed of Southern African-Americans became a part of the story of corruption, as well as part of the national fear of Populism, socialism, and communism. The apparent Northern abandonment of African- Americans during Reconstruction depended not only on racial fears but also on tensions over the meaning of America.”

—Heather Cox Richardson

With certain exceptions, like John Brown, for example, Northern Republicans themselves held what would now be called racist views, and they were not keen on bringing black workers north. Their most popular idea was that the South—which they regarded as an underdeveloped “wilderness,” could be profitably developed, by employ black workers there (meaning not in the North as labor competition).

Ideologically, the labor question was entangled with a debate with which we’re still familiar: big government versus small government. There’s more emphasis in Foner on the role of the 14th Amendment in the strengthening of the central state, and more on the 13th by Richardson, but again we risk being arcanely sidetracked. Where the small government advocates held sway in both parties, as early as 1867, Republicans were pulled into the radical (big government) camp by the violent resistance of powerful Southerners. Meanwhile, rapidly organizing Southern blacks were adopting political views that emphasized both class struggle and redistribution, echoing European radicals (the Paris Commune, from which “commun-ists” would take their name, was established in 1871 [only to be crushed within weeks]).

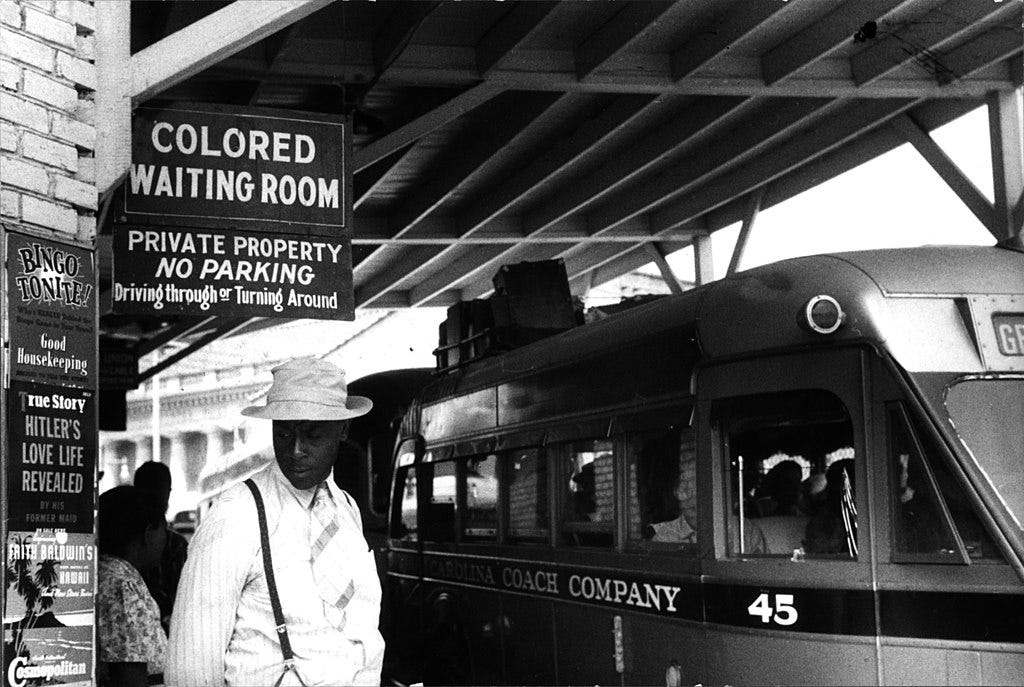

The free labor movement, along with almost all Republicans and Democrats, regarded these European ideas to be anathema. By the mid-1870s, former advocates for black workers in the South, who’d once sung their praises, were referring to black workers in now familiar terms: lazy, shiftless, naturally criminal. Long story short, by 1877, when Reconstruction was officially ended, opening the door to the Jim Crow era, the disfranchisement of Southern blacks met with Northern white acquiescence and even support.

We need to preface the formal enactment of Jim Crow laws with a story from North Carolina—my home state for 23 years.

“Let them understand once and for all that we will have no more of the intolerable conditions under which we live. We are resolved to change them if we have to choke the current of the Cape Fear with carcasses. Negro domination shall henceforth be only a shameful memory to us and an everlasting warning to those who shall ever again seek to revive it.”

—Alfred Moore Waddell

In the 1890s, amid the general enactment and enforcement of draconian segregation laws throughout the South, the majority black coastal city of Wilmington was run by the Fusionists, a biracial political coalition of mostly black Republicans and Marion Butler’s North Carolina branch of the Populist Party, mostly white farmers.

In the years leading up to 1898, Wilmington stood as the most progressive city in the American South. A bustling, integrated port, the town, historians say, “was what the new South could have become after the Civil War.”

By 1896, nearly 126,000 Black men in Wilmington were registered voters. The city’s flourishing Black middle class boasted some 65 doctors, lawyers and educators, scores of barbers and restaurant owners, public health workers, members of the police force and the fire department. And just three decades after Emancipation, Black Republicans held multiple positions of power, serving as city councilmen, magistrates and other elected officials.

The integration resulted from Fusion politics, a political phenomenon in North Carolina that joined the Populist Party (comprised mostly of poor, white farmers) and the Republican Party (the political affiliation of choice for freed Black Americans) into one entity. They aligned against the Democrats, a party composed of wealthy white segregationists who white populists believed cared more for the interests of banks, railroads and affluent constituents than of the common man.

Together, the Populists and Republicans seized the political majority, sweeping the state in 1894, electing Republicans to local state and federal seats and ousting Democrats from political power.

—Aaron Randall, “America’s Only Successful Coup d’Etat Overthrew a Biracial Government in 1898”

What would come to be known, but seldom taught in school history courses, even in North Carolina, as the Wilmington Massacre, was a final and decisive blow to black social and political power that had gestated inside the troubled womb of Reconstruction.

White coup-makers in Wilmington, proudly posing in front of a black business they’ve just burned.

The events would be revised by white supremacists to characterize the coup/massacre as virtuous white men putting down a dangerous black rebellion, called the “Wilmington Race Riot.” After the massacre, a sham election was held, with armed white men threatening black voters away from the polls, “electing” all white Democrats.

The propaganda inflaming white men to commit the massacre, and justifying it afterwards, came to be standard fare for white violence under Jim Crow, which was likewise never prosecuted. The Jim Crow era is typically dated from 1896 to 1965, during which there were estimated to be over 4,000 lynchings. That justification was the “threat” posed to white women by black men.

Prior to the attacks, Alex Manley, the biracial editor of Wilmington’s largest newspaper, The Daily Record, wrote an editorial excoriating the white supremacist editors of the state’s largest paper, The News and Observer (still North Carolina’s capital newspaper), for its repeated claims about “black brutes” with their eyes fixed on fragile white womanhood.

In fact, in and around Wilmington, interracial pairings, including marriage, were not uncommon; and this appeal to white male sexual terror proved devastatingly effective for the next seven decades.

Manley’s article not only dressed down this narrative, he dared to point out the continuing reality of white men raping black women with no legal consequences. This further infuriated the white supremacists, becoming the emotional fuel for the massacre. The Big Black Buck trope continued to do its work until and even after the legal destruction of Jim Crow.

The first blockbuster film in the US was D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, which glorified the Ku Klux Klan as protectors of white womanhood, was viewed privately by an adoring President Woodrow Wilson. Denounced by the NAACP—organized in 1909 by W. E. B. Du Bois, Mary White Ovington, Moorfield Storey, Ida B. Wells, Lillian Wald, and Henry Moskowitz—the silent movie nonetheless grossed more than any film in history then, and still, comparatively speaking throughout the history of film.

Obviously, there was resistance to this narrative and to Jim Crow generally, as the list of NAACP founders above shows. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People was organized in Baltimore, and remains a political actor to this day.

NOTE: If you want to know black history, you need to learn about the Niagara Movement. No way around it. And to learn about that, you have to know about Plessy v. Ferguson. Hit the links and read the articles, and you’ll at least know more than pretty much anyone and everyone who doesn’t care about black history. (I told you, we can help.)

Organizers of the Niagra Movement

Furthermore, to know African American history, one would need to become familiar with the various and contradictory theories and movements that grew up in response to early twentieth century Jim Crow. Three distinct and major trends took hold, the DuBoisians, the Garveyites, and the Washingtonians, named for leaders W.E.B. DuBois, Marcus Garvey, and Booker T. Washington.

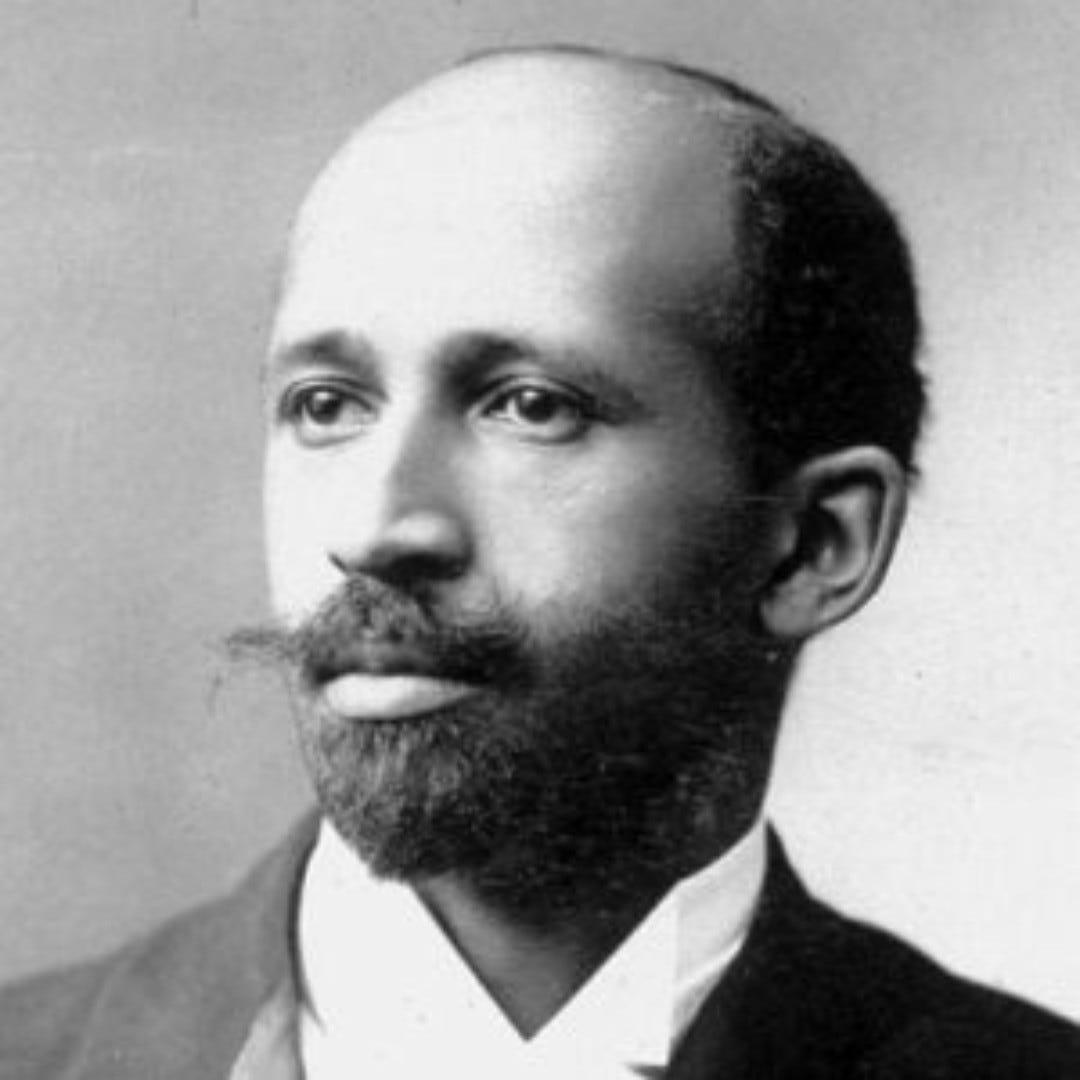

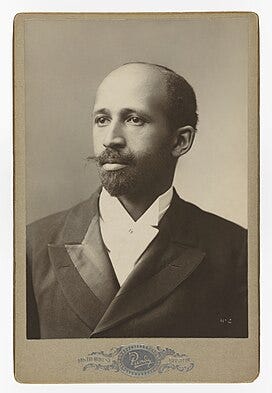

DuBois

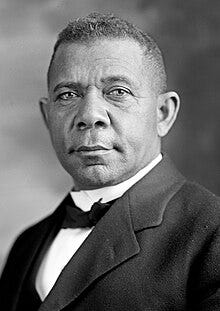

Washington

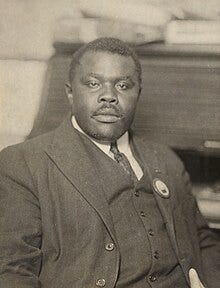

Garvey

Too briefly to do this real justice, DuBois advocated for full equality and integration now. Washington advocated for a slower approach, maintaining segregation, and using internal black uplift strategies (especially education) to prove themselves to the larger society for eventual integration. Garvey believed white society would never accept blacks, and so argued for separatism (and uplift through education and capital accumulation), and even an eventual return of blacks to a liberated “Africa” (scare quotes, because there is no one “Africa” in any but the crudest geographical sense). DuBois and Garvey, who agreed on little else, were “pan-Africanists,” that is, they connected colonialism with domestic racism. (In fact, “scientific” race theory was absolutely invented within and for the capitalist-imperial milieu.)

DuBois helped organize the NAACP.

Washington organized the Tuskegee Institute.

Garvey organized the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA-AC).

To put this in perspective and avoid anachronistic Monday morning quarterbacking, they all saw the same things, but theorized it differently, and while many now denounce Washington’s accommodationism, it’s important to point out that the ultimate threat hanging over the head of African America wasn’t just a future of disenfranchised sharecropping and service work; it was extermination.

Then everyone’s problems were compounded by the Great Depression (1929-1939). This is where the communists came in—another chapter that’s been erased from even black history in the US (DuBois himself eventually joined the Communist Party and decamped to Ghana). This is also when we see a different kind of more currently recognizable accommodationism come into play.

Not only were there many notable black communists, there was a vibrant US Communist presence in the South, especially in Alabama. Book recommendations would include Mary Stanton’s new book, Red, Black, White: The Alabama Communist Party, 1930–1950, Robin D.G. Kelley’s Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communists during the Great Depression, and Black Worker in the Deep South, by Hosea Hudson.

[B]eginning in the 1930s, many of the leaders and organizers in the struggle against segregation and Jim Crow were members of the Communist Party or its fellow travelers. From Harlem in New York City to Birmingham, Ala., black and white Communists organized across racial and class lines throughout the Great Depression and World War II to fight fascism abroad and hunger and racism at home. By the time the Southern Negro Youth Congress was organized, many involved in the burgeoning civil rights movement had been active in earlier Communist and Communist-affiliated groups. Others who were radicalized by the trial of the Scottsboro Boys and the Angelo Herndon case were exposed to many radical economic ideas and felt a particular loyalty to the left, having witnessed in both trials the Communist Party backing lawyers to take up the cause of black civil and legal rights in the South.

—Robert Green II, “A Southern Vanguard”

American Communists didn’t only mount the defense of the Scottsboro boys, they helped found and support the African Blood Brotherhood (mostly West Indians), the American Labor Negro Congress, the Sharecroppers Union, and the multiracial Southern Tenant Farmers Union.

Read about the Scottsboro Boys here. Read about the Angelo Herndon case here.

Initially, the NAACP refused association with the Communists, because they didn’t want to inflame the Black Beast narrative through defense of the Scottsboro Boys, falsely accused of raping two white women in 1931. Eventually, the NAACP joined in the defense of the Scottsboro boys, but even then this resulted in increased tension within the NAACP.

The case only exacerbated existing inter-tendency tensions in the NAACP, manifest in a growing conflict between DuBois and the organization’s President, Walter White. DuBois resigned from the organization in 1934.

In that same year, the American Communist Party (CPUSA) radically altered it failing overall strategy, and participated in organizing the Popular Front to oppose capitalist exploitation at home and the rise of fascism abroad.

Southern Tenant Farmers Union gathering, Arkansas, 1937

The Communist Party by 1934 was willing to form alliances with progressives and socialists. It began to assist agricultural workers to allied various organizations from the South in order to create a stronger Popular Front. The STFU was among many unions to take part in this Popular Front. The STFU benefited from its association with the Communist Party because the organizations in the Front supported each other in protests and fights against plantation owners. Not every member of the STFU belonged to the Communist Party.

There was a caricature of the CPUSA as slavish Soviet robots, which in foreign policy wasn’t far off the mark; but in its domestic actions, it was an agile and effective force during the Great Depression and even until World War II, combining the working class struggle and the fight against Jim Crow more effectively than any other formation at the time.

The Popular Front of communists, socialists, and social democrats took up a multiracial working class politics that gave rise to the initially formidable Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO, which wouldn’t fall prey to class accommodationist bureuacratization until after World War II), and, less well-know, the Southern Tenant Farmers Union, based first in Arkansas and spreading through the region, which would eventually join with the CIO’s ag-affiliate, the United Cannery, Agricultural, Packing, and Allied Workers of America (UCAPAWA).

STFU President H.L. Mitchell (L) and Vice President E.B. McKinney (R)

This is not to say that biracial coalitions didn’t have to deal with racial tensions. They definitely did, in every case, going as far back as Newton Knights Mississippi militia and beyond.

Short excursus on linguistic representation.

It was this association with Communists, and something called the national question, that still underwrites the non-hyphenated (and contested) term “African American,” still employed by people within what is called the Black Radical Tradition, a term first used by Cedric Robinson, in his book, Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition. (Full disclosure: the author has an affinity with this tendency, and it has strongly influenced his thinking on these matters.)

African American, then, points ultimately not to “race,” a questionable category at best, but racial-ized culture; and culture, after all, is transmitted across generations in myriad and granular ways. The Southern communists of the Depression era, black and white, were reading from the Bolshevik playbook on “nationality,” nation here referring not to a nation-state (yet), but “a social group with a collective identity based on shared features such as language, history, culture and-or territory.” I myself belonged once to Freedom Road Socialist Organization (now called Liberation Road), a Marxist formation that theorized and advocated for “the Black nation,” whose territory was roughly defined as the Black Belt (named for the color of the soil, not black people), especially the contiguous region from Maryland to Louisiana and Arkansas, surrounding majority black counties across the South.

This orientation among organizers during the Depression and the pre-World War II era blurred the boundaries between what might be called the DuBoisians and the Garveyites—an early identity politics of a sort (“a social group with a collective identity based on shared features such as language, history, culture and-or territory.”), but one that still kept class struggle at the forefront, and which didn’t foreclose inter-“national” alliances.

The term African American was employed (in writing) as a “correction” to the hyphenated African-American to represent a nationality, in the sense noted above, as opposed to a subset of American. This, of course, was a later linguistic development, following on “colored,” “Negro,” and Black, or black. (As is still the case today, political factionalism is in part characterized by struggles over terminology.)

When this (“white”) author uses African American as preferred terminology, it is in the cultural (not separatist) sense, acknowledging that, while imperfect, the national/cultural lens is theoretically insightful and informative, but it does not, in fact, represent any separate political entity, nor does it ignore or dismiss the fact that, post-desegregation, these boundaries have progressively blurred in many sectors of American society. The problem with this characterization, the limits of its utility, and its hidden dangers are best outlined by Adolph Reed:

[A] common interpretive tendency in the fields of black politics, black American political history, and black studies generally [is] to posit as a central critical analytical category an idealized “black liberation movement,” “black freedom movement,” or “black community” that in effect exists outside or logically and normatively prior to larger political dynamics in American society and political economy. In positing a false coherence, this interpretive posture, which has its roots, as Cedric Johnson’s and Dean Robinson’s work shows definitively, in Black Power and post-Black Power communitarian radicalism, has been problematic—I’d argue counterproductive—in both scholarly and civic domains. From its earliest iterations as a leftist or racial populist critique of the limitations of Black Power as ideology and program, going back to the end of the 1960s in Robert L. Allen’s Black Awakening in Capitalist America and to some extent Harold Cruse’s critiques of Black Power ideology,19 that interpretive posture preempted recognizing how emergence of a stratum of public functionaries and aspirants had the potential to alter radically the practical universe of the political for black Americans across the board, from the most mundane aspects of quotidian life on up to larger questions of the nature and direction of public policy at all levels.

Such analytical purblindness was understandable at that historical moment both because the new political regime had not begun to take concrete shape and because the rhetorical force of the struggles against racial exclusion and discrimination reasonably presumed a collective or unitary and popular black interest in opposing racism and racially discriminatory treatment. Furthermore, the popularity of anticolonial metaphor gave a radical patina to formulations of black Americans as a singular “People.” As a standard of critical judgment, however, that perspective was never adequate for the interpretive or political challenges presented by the evolving post-segregation order or the revanchist turn in national politics begun in the 1970s and its many ramifications down to states and cities and the lives of all working people as that political turn consolidated on bipartisan terms and intensified over subsequent decades. (Political scientist Alex Willingham, in an article originally published in 1975, was probably the first to articulate a clear understanding of the limits of black radical ideology in this regard.20) It can lead only to dead-end arguments—the parallel to pointless debates about whether or not some individual or stance is racist—about whether individual or program X really represents the interests of the black community or is a “sell out” or inauthentic.

In our current political moment, in which even flamboyantly race-conscious black people embrace career opportunities and ideological rationales attendant to the destruction of public education, privatization of public goods and services, and the dynamic of rent-intensifying real estate development commonly described as gentrification or neighborhood upgrading and revitalization, formulations that presume an idealized “black community” or “black masses” as a collective political subject obscure the real processes through which the larger revanchist regime gains legitimacy among black officials and citizens as its imperatives take on the character of pragmatic common sense. An extreme, or extremely ironic, illustration of this accommodation is Howard Fuller, once also known as Owusu Sadaukai, who was a legendary Black Power radical in North Carolina, a key figure in 1970s Pan-Africanism, then a Marxist-Leninist-Mao Zedong Thinking trade union activist. Some time after returning to his Milwaukee hometown, Fuller became the city’s school superintendent and established a reputation as a teachers’ union foe, and is now the founding eminence of the Black Alliance for Educational Options, the main black pro-voucher, pro-charter, militantly anti-teachers union organization. However, dramatic cases of radicals’ apparent conversion are less meaningful than are the many, far more insidious instances of following “natural” trajectories along a track of NGO-driven “community activism,” as Arena describes, or other forms of “doing well by doing good” that lead precocious undergraduates to Teach For America and other organizations of neoliberalism’s Jungvolk. Similarly precocious public officials like Cory Booker or Barack Obama insistently define racial aspirations—indeed all concerns with social justice—in line with the interests of financial capitalism, and many, many others all down the pyramid of social standing and power also imagine individual futures and “success” in savoring fantasies of pursuing personal advantage by operating within what a broader perspective reveals are the structures of neoliberal dispossession. An interpretive posture that posits an unproblematic “black community” or “black masses” as a normative standard cannot adequately conceptualize the relatively autonomous tendencies toward neoliberal legitimation in black politics; much less can it confront them politically.

End excursus

Tensions between black leadership have plagued what might be generalized as the American black freedom struggle from the outset. This isn’t unique, but a feature of politics more generally, the exceptional moments of solidarity always provoked by some shared traumatic event or circumstance.

It needs saying here that many of the Southern black leftists of the period remained Christians, unlike many of their white counterparts.

References to God and the Bible appeared rather frequently in letters from Alabama’s black radicals. “Your movement is the best that I ever heard of,” wrote a black woman from Orrville, Alabama. “God bless you for opening up the eyes of the Negro race. I pray that your leaders will push the fight. . . . I am praying the good Lord will put your program over.”

Nearly all black rank-and-file Party members attended church regularly, and in Montgomery black Communists initiated the . . . practice of opening their meetings with a prayer.

—Robin D.G. Kelley, Hammer and Hoe

After World War II, the black freedom struggle was centered in the one place where the most black people congregated each week: churches. Before we begin to delve into the post-war period, let’s look at the war period itself.

The following is an excerpt from my book, Borderline.

«Our cultural memory of World War II in the United States has been constructed by film as much as any other medium. Whether battle hagiographies like A Bridge Too Far and The Sands of Iwo Jima, or biographies like Patton, or “band of brothers” films like The Big Red One and Saving Private Ryan, war-critical naturalism like Das Boot, the theologically-inflected The Thin Red Line [my personal favorite], or Nazi-milieu accounts like The Pianist and Schindler’s List, World War II films rarely show the ways in which the war was publicized and promoted in the United States as a white man’s war. The Good War narrative that invariably overwrites accounts of World War II—based on the horrors of the Hitler regime—is embarrassed by the actual degree to which white racism … was incorporated into both practice and ideology in the preparation for and prosecution of the war …

Tom Brokaw, in his popular book of the same name, called the Americans who fought during World War II “the Greatest Generation.” His account of that generation is closely reflected in Steven Spielberg’s award winning film Saving Private Ryan, featuring Tom Hanks as the protagonist detachment’s leader, Captain Miller.

Miller’s characterization [is] as benevolent father figure to his subordinates, whose respect he commands with gentle authoritativeness. Miller and his men must find and protect the titular Ryan (Matt Damon), who is to be sent home following the deaths of his brothers in combat. Upon locating Ryan, Miller enacts paternal protectiveness in extremis, using himself as a human shield, and sacrifices himself to martyr his ideal configuration of wartime masculinity. (Hannah Hamad)

“Greater love has no one than this,” as the Gospel says (John 15:13). This is a story of sacrifice and honor, inflected with Christian-esque martyrdom.

Vin Diesel’s [biracial black-white actor] character, Caparzo, the first of the band to be killed, is vaguely “ethnic” [Italian] in appearance and speech, and has a Jewish pal, Private Mellish, whose bout of weeping when he is given a Nazi youth knife reminds us that the purpose of the war is to stop the Nazi anti-Semites. A young Southern white man is the detachment sniper, fighting alongside New Yorkers, under the Midwestern schoolteacher who commands them. As close as Spielberg can get, without reminding us that black soldiers were in strictly segregated units, he constructs a pluralist microcosm in the detachment.

The reality in the United States when it went to war with the Axis Powers was Jim Crow in the South, deep structural racism in the north, widespread white hatred of Asians, and Jewish social exclusion. When the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference was held in 1944, as the end of the war came into view, it had to select a site in New Hampshire, because earlier choices for conference sites … did not allow Jewish guests, and several of Roosevelt’s Treasury staff, including Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau, were Jewish.

In 1943, between May and August, there were five racial riots in the United States. In May, while German U-boats were being scattered by the United States in the Atlantic, five black Mobile, Alabama, shipyard workers, involved in war production, were promoted to welding positions. White workers organized a four-thousand-strong mob that was allowed onto the work sites by management, which proceeded to attack black workers with bricks and tools, leading to a mass exodus of black workers following the riot.

In early to mid-June, while Allied bombers hit Naples and Sicily, Los Angeles-based white Navy men had become involved in a series of altercations with Mexican-American and African-American youths, who had established a local subculture that included wearing baggy suits called “zoot suits.” Beginning on June 3rd, the Navy men organized themselves into phalanxes, rode in taxicabs to places where the “zoot-suiters” were known to hang out, and moved through the streets with clubs, beating hundreds of young men—many as young as thirteen and fourteen—and every person who tried to defend them. The Navy men stripped their victims in the street, then urinated on their suits before burning them. This went on for almost two weeks before the Navy Shore Patrol stopped it, declaring the navy perpetrators innocent and claiming they had acted in self-defense.

In mid-June, as the U.S. was winning a decisive battle at Guadalcanal, a riot broke out in Beaumont, Texas, another war production center. Based on two separate accusations from white women that they had been sexually assaulted by black men, white workers led by members of the Ku Klux Klan organized a mob of, again, around four thousand, which marched into the African American section of town, injuring more than fifty people and killing three, destroying local black businesses, and ransacking more than a hundred black homes.

In late June, while the Allies prepared to bomb the Ruhr industrial valley in Germany, in another stronghold of the Ku Klux Klan, Detroit, a fight between a black worker and a white Navy man ignited a racial tinder box, and a three-day street melee erupted between blacks and whites that resulted in more than eighteen hundred arrests, six hundred injuries, and thirty-four dead, twenty-five of them black—and seventeen of those killed by police.

On August 1st, while the Germans gassed 2,897 Roma and U.S. bombers hit German-controlled refineries in Romania, a New York City policeman struck an African American woman, and a black soldier named Robert Bandy tried to intervene. The policeman shot Bandy, wounding him. Bystanders who were outraged began spreading the word. The rumor circulated that Bandy was dead. A riot ensued, fueled by years of resentment against white law enforcement in Harlem, and the violence resulted in six dead, more than four hundred injured, and more than five hundred arrests.

The industrial war forced the state to mobilize as many resources as possible. Black men were hired into war production with white men, and women entered wage labor in unprecedented numbers. Depression-era unemployment and the sudden explosion of war jobs launched waves of migration, shuffling the American demographic deck. [The Great Northern Migration]

The United States found itself denouncing Nazi racism even as it actively pursued a racist ideological attack on the Japanese and maintained a racial caste system inside its own borders. The white masculinity that buttressed the war would be thrown into crisis by early setbacks against the Japanese that challenged “white superiority.” After the war, the eventual discovery of the scope and brutality of Nazi atrocities would expose the exterminist seed lodged within the category “white.”

[Interjection: this was when the CPUSA disgraced itself, at the behest of Stalin, by supporting Roosevelt’s racist internment of Japanese-Americans.]

There was an ideological reformation during the war, and the category white had to be expanded to mobilize more support for what was still constructed as a “white man’s war.” By the end of the war, the office of War information (OWI) found itself selling the idea of a racially pluralist and democratic America, and once that fiction was before the public, as the nation would discover in the years after the war, it would be impossible to take back.» (end excerpt)

In Palo Alto, California, December 1946, black war veteran John T. Walker had his house set afire, with a note that read: “We burned your house to let you know that your presence is not wanted among white people. You should know by now we mean business. Niggers who are veterans are making a mistake thinking they can live in white residential districts. Since you are a veteran, we are warning you for the last time to clear out. If you were not a veteran, you would be dead now. Usually the Klan strikes without warning, but since you are a veteran, we have been unusually kind in giving you a chance to save of your black hide.”

“I think one man is just as good as another so long as he's honest and decent and not a nigger or a Chinaman. Uncle Will says that the Lord made a white man from dust, a nigger from mud, then He threw up what was left and it came down a Chinaman.”

—Harry Truman, 1911

In July 1948, President Harry Truman signed Executive Order 9981, officially desegregating the US Armed Forces and the Federal Government. What provoked this man who referred to the white house wait staff as “an army of coons,” to order the most sweeping desegregation measure since Reconstruction? Well, as I said in Borderline, “By the end of the war, the office of War information (OWI) found itself selling the idea of a racially pluralist and democratic America, and once that fiction was before the public, as the nation would discover in the years after the war, it would be impossible to take back.” That narrative exploded on February 12, 1946.

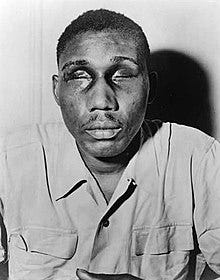

Sergeant Isaac Woodard Jr., just discharged and still in uniform with his battle stars from the Pacific Theater and his NCO chevrons, was arbitrarily ejected from a bus by its driver in Batesburg, South Carolina. The driver called the local Chief of Police, Lynwood Shull, who arrived with several other policemen, and demanded that Woodard produce his discharge papers. When he did, hey took him into an alley, beat him with nightsticks, and arrested him. In the jail, the beating continued, totally blinding Woodard in both eyes.

The story outraged much of the public, the memory of the war still fresh, and galvanized black Americans, including 900,000 black veterans. The refusal of South Carolina to take action generated such pressure on the White House, and on the post-war pluralist narrative, that Truman was compelled to launch a Federal investigation.

In June 1947, he gave an historic speech to the NAACP, becoming the first American President to do so. The man who’d referred only eight years earlier to the White House staff as “an army of coons” said:

We must keep moving forward, with new concepts of civil rights to safeguard our heritage. The extension of civil rights today means, not protection of the people against the Government, but protection of the people by the Government.

We must make the Federal Government a friendly, vigilant defender of the rights and equalities of all Americans. And again I mean all Americans.

As Americans, we believe that every man should be free to live his life as he wishes. He should be limited only by his responsibility to his fellow countrymen. If this freedom is to be more than a dream, each man must be guaranteed equality of opportunity. The only limit to an American’s achievement should be his ability, his industry and his character. The rewards for his effort should be determined only by these truly relevant qualities.

Our immediate task is to remove the last remnants of the barriers, which stand between millions of our citizens and their birthright. There is no justifiable reason for discrimination because of ancestry, or religion. Or race, or color.

Thirteen months later, he signed Executive Order 9981. This was the second major step by the government on the still long road to ending Jim Crow (the first was Executive Order 0082, signed by FDR, which ordered the desegregation of war industries—see below).

My own prehistory is written here, because my exit from the enclosure of “white” culture and into a pluralistic one was when I joined the Army (and came to make a career of it). Because of the draft, during my first assignment (to Vietnam), my unit (the 173rd Airborne Brigade) was almost 50 percent black.

Hisorian Leon Litwack called 1946, the year of the police attack on Sergeant Isaac Woodard Jr., “the true birth of the Civil Rights Movement.” In 1940, NAACP membership was around 50,000. By 1946, its ranks swelled by black war veterans, that number exceeded 450,000.

The attack on Sergeant Woodard was motivated by a more general fear in the South that soldiery would embolden black Americans and create economic havoc as many refused to return to sharecropping. The latter turned out to be true, enabled by burgeoning industries in the North and out West. Six million Southern blacks left, mostly headed to New York City, Chicago, Detroit, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Philadelphia, Cleveland, and Washington, D.C., where unionized factory jobs were abundant.

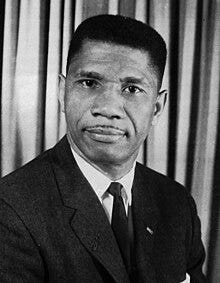

In 1944, Smith v. Allwright had ruled that blacks must be allowed to vote in Democratic Primaries. All manner of skullduggery was employed to defy the order, but it’s very existence as law gave focus to freshly aroused African Americans. Civil Rights martyr Medgar Evers began his activist career in 1946 with his brother, both war veterans, registering black voters. In 1946, citing Smith v. Allwright, more than 600,000 black Southerners registered. There was now a singular point toward which the masses could mobilize: the franchise.

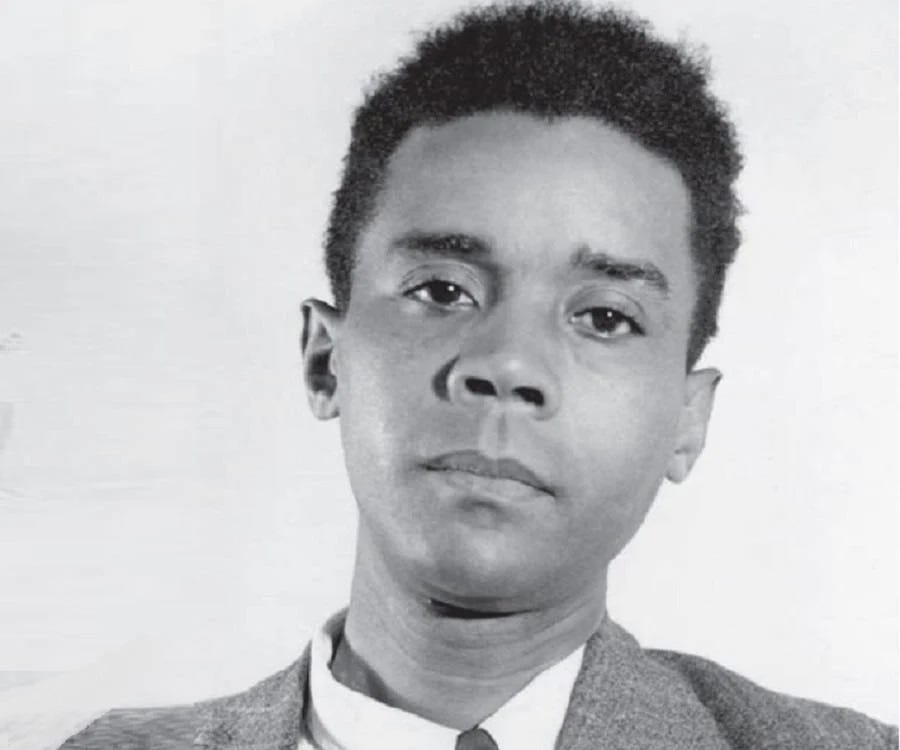

Medgar Evers, 1943 (assassinated in Jackson, Mississippi, 1963—37 years old)

These efforts were met with barbaric violence for the next 25 years.

One notable event (in 1946, of course) was the “Columbia race riot,” in Columbia, Tennessee, where black Navy veteran and welterweight boxer) James Stephenson punched out a white store owner who assaulted Stephenson’s mother. Stephenson was arrested, then bailed out by a local black businessman. A lynch mob was organized, an ad hoc black militia of around a hundred men was organized, leading to an armed confrontation between the mob—which was augmented by police—and a force of State Police were called in, who came in, ransacked the black business district, and arrested black men.

This was to be future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall’s first big case on behalf of the NAACP; and he won 23 acquittals before an all white jury.

The shit, as they say, was on.

Here, we need to back up again for a moment, and return to the variously evolving strategic “tendencies” among black leaders. In particular, I want to focus on A. Phillip Randolph (1989-1979).

Randolph was one of the most consistently radical figures in black politics and one of the greatest socialists of the twentieth century. His work made an impact on almost every major development in black politics from the 1920s to the 1970s.

—Paul Prescod

A. Phillip Randolph life and work cut a straight line from before the Great Depression to the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.; and touches on the tribulations of black historical political tendencies. Basic reading: A. Phillip Randolph: A Life in the Vanguard, by Andrew E. Kersten.

Randolph was a socialist and a trade unionist, who’d cut his teeth on activism by organizing the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, founded in 1925. The BSCP was the first black led and black majority labor union in the US, which won recognition after twelve years of intense struggle, in which the three-pronged resistance to unionization came from (1) spies planted among the porters, (2) layoffs, and (3) black institutions that themselves were anti-union (like Howard University).

Looping back to the Washington-DuBois-Garvey era, Randolph was raised in Florida, the son of a tailor/AME minister and a seamstress. He came of age just after the turn of the century, just as Booker T. Washington died, as W.E.B. DuBois was founding the NAACP, and Marcus Garvey the United Negro Improvement Association. There were ferocious debates between DuBois and Garvey against the dual backdrops of (a) Washington’s influence as a white-recognized black leader and (b) Jim Crow. The antagonism between Garvey and DuBois occasionally descended into black colorism, with DuBois referring to Garvey as “a fat black man,” and Garvey denouncing DuBois as a “mulatto.”

Of the two—DuBois being a more remote intellectual— Garvey was far and away the more influential among the African American poor. His emphasis on the intractability of white racism matched their experience; his fantasy of a New African Empire was contagious; his militant cultural pride narrative was bracing; and his goal of racial uplift through black capitalism seemed more readily accessible. Both shared a theoretical notion of a black vanguard, Garvey’s an entrepreneurial class, and DuBois appealing to the notion of a respectable-intellectual “talented tenth.” (This was the milieu in which Zora Neale Hurston, who wrote about black country [as opposed to urban] folk, and she lampooned these urban visionaries as “race men,” saying once, “I do not weep at the world. I’m too busy sharpening my oyster knife.”)

It was in this cauldron of competing ideas that Randolph began his public life after having decamped from Crescent City, Florida to Harlem in New York City. It was there that Randolph became a socialist, t on point joining the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). His first foray into trade unionism was opening an employment office for Southern blacks who’d traveled north for jobs, through which he also proselytized them on the virtues of unionization. There was already a glimmer of Randolph’s lifelong strategic sense that political projects needed to be pursued through local mass institutions—especially labor organizations.

Between DuBois and Garvey, Randolph was a DuBoisian. Randolph came to despise Garvey (who Randolph himself, years earlier, had introduced to the Harlem political scene) as a fantasizing impediment to practical politics, a mis-leader of the masses. Garvey’s ideas had become increasingly unhinged, calling himself “the Provisional President of Africa,” selling shares in his mismanaged “Black Star Line,” aka “Black Cross Navigation and Trading Company,” and wearing a bizarre military costume as part of his shtick. Nonetheless, his cult of personality remained strong for years.

Randolph called him a “charlatan” who was making his black acolytes a “laughingstock.” Garvey even met with Klan leader, Edward Young Clarke, to discuss separatism, provoking Randolph’s Messenger magazine (a black socialist literary publication out of Harlem) to publish an article titled “Marcus Garvey! The Black Imperial Wizard Becomes Messenger Boy of the White Klu Klux Kleagle.”

The Messenger also denounced Booker T. Washington’s accommodationism as “the cheap peanut politics of the old reactionary Negro leaders.”

Such divisions have plagued black politics, and remain today. Hurston versus urban “respectability,” DuBois/Randolph versus Garvey, James Baldwin versus Richard Wright (the black representation debate—see also, e.g., Spike Lee versus Tyler Perry), Mary Church Terrell versus Mary McLeod Bethune, Martin Luther King Jr. versus Malcolm X, and Cornell West versus Obama/Michael Eric Dyson. Which is not to say this is a “black” phenomenon—political splitting is built into the practice of modern politics; but to point out specifically how these particular differentiations are manifest in American black history.

[W]hat is problematic about a common interpretive tendency in the fields of black politics, black American political history, and black studies generally [is] to posit as a central critical analytical category an idealized “black liberation movement,” “black freedom movement,” or “black community” that in effect exists outside or logically and normatively prior to larger political dynamics in American society and political economy. In positing a false coherence, this interpretive posture, which has its roots, as Cedric Johnson’s and Dean Robinson’s work shows definitively, in Black Power and post-Black Power communitarian radicalism, has been problematic—I’d argue counterproductive—in both scholarly and civic domains. (Adolph Reed)

Randolph would eventually part ways with DuBois, specifically over DuBois’s early theories about the “talented tenth.” (He also disagreed with DuBois’s support for American participation in World War I.) Randolph believed (as DuBois would later) that liberation for black Americans was only possible through economic transformation, i.e., working class politics. He said that vanguard/respectability/paragon politics are inevitably self-limiting.

I didn’t feel there was the necessary racial and social and economic militancy of the Talented Tenth to give strength and force to the liberation of the black masses. The Tenth represented little more than a mere revolt against discrimination. They had no fighting force in them. So where real radicalism was concerned, they were like window dressing.

_A. Phillip Randolph

(The successes of Oprah and Obama, in other words, do little to nothing to materially improve the lives of the vast majority of black people.)

With this in mind, he organized the BSCP, where he came into conflict with his wife’s alma mater, Howard university, in another instantiation of intra-racial class conflict.

All the important forces within black life seemed to be on the side of the bosses — the dean of Howard University came out publicly against “Negro unionism,” most black churches wouldn’t let speakers from the porters’ union use their platform, and black newspapers denounced the organizing effort.

To compound difficulties, white trade unionists of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) (unlike the Communist influenced CIO) was racist to its core, the AFL explicitly barring black membership.

The fortunes of trade unionism changed as President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal came to include strong pro-labor legislation and policy. This was when the BSCP won it’s most dramatic victory in 1937: reduction from 400 to 240 hours work a month at nearly double the hourly wage.

Not content with this victory, Randolph—who saw World War II approaching fast—set his sights on integration of workers in the growing war industry. His strategy for this was the organization of the (first) March on Washington Movement (MOWM. 1941-6), for which he organized through the BSCP membership, which reached everywhere with passenger trains.

It was a bold plan, and there was no precedent for it. This was not a movement predicated on the direction of middle-class leaders, or the mobilizing of intellectuals. This movement directly organized and mobilized working-class black America. Randolph and the BSCP campaigned in bars, barbershops, and wherever black people actually lived and worked.

The momentum drew in the mainstream civil rights organizations that didn’t want to be outflanked, such as the NAACP and the National Urban League. Still, it was mostly the porters that funded its activities. Mass rallies of thousands were held in major cities, and people even began to speculate whether a hundred thousand people would go to the march. (Prescod)

The aim was to scare the living shit out of President Franklin Roosevelt, who was trying to consolidate American unity in preparation for the war. Roosevelt invited Randolph to the White House to plead against the march, but Randolph stuck to his guns, eventually agreeing to stand the march down only in exchange for Roosevelt integrating the war industries, which he did in 1941 with Executive Order 0082, backed by the creation of the Fair Employment Practices Commission (FEPC).

The youth wing of the MOWM, which remained intact to keep tabs on the relatively weak FECP, included a young, Quaker-influenced ex-Communist named Bayard Rustin. Some of the tactics of the MOWM included boycotts, sit-ins, rallies, and marches, and these would later be employed to pressure Harry Truman (facing a war in Korea) to desegregate the military.

The embryo of the Civil Rights Movement began to grow. Among the main organizers of the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955-56 were E.D. Nixon, a member of BSCP, Bayard Rustin, a seamstress and local NAACP activist named Rosa Parks, and a young Baptist preacher named Martin Luther King Jr. (Read here about the Highlander Folk School and the development of the boycott strategy. There was nothing spontaneous about it. Also see Septima Clark, who taught at Highlander.)

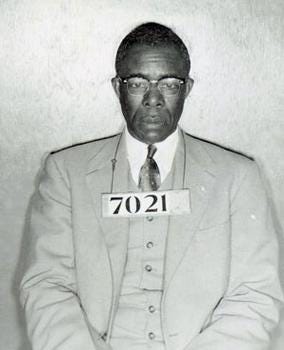

E. D. Nixon

Rosa Parks (MLK in bg)

Martin Luther King Jr.

While Randolph’s role in the Montgomery Bus Boycott was tangential, the Civil Rights Movement that it engendered owed its strategic orientation to Randolph, which would culminate in 1963 with the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, headlined by King, and organized by Randolph and Rustin, to which we’ll also return.

Tying some threads, Rosa Parks’ first activism was around the Scottsboro Boys. Likewise, Rustin was involved with the Scottsboro case. (Parks’ lawyer, Clifford Durr was also an interesting character.)

For your friends who may be disinclined to read, and who can tolerate a bit of historical license, show them the 2001 film, Boycott.

The boycott brought Martin Luther King, to which we’ll also give more attention soon, into the national limelight, and King was selected to lead the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, founded after the boycott. The SCLC took shape from the 1957 Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom in Washington, DC.

By now, it was clear, that the continued struggle would be church-based, and based on he Gandhian/Christian-pacifist principle of non-violence that was explicated to King and other Southern leaders by the Quaker-influenced Rustin—and which he himself had learned as a member of the Congress of Racial Equality (see below), through a close study of the Salt March during the Indian struggle for independence from Britain.

END PART 1