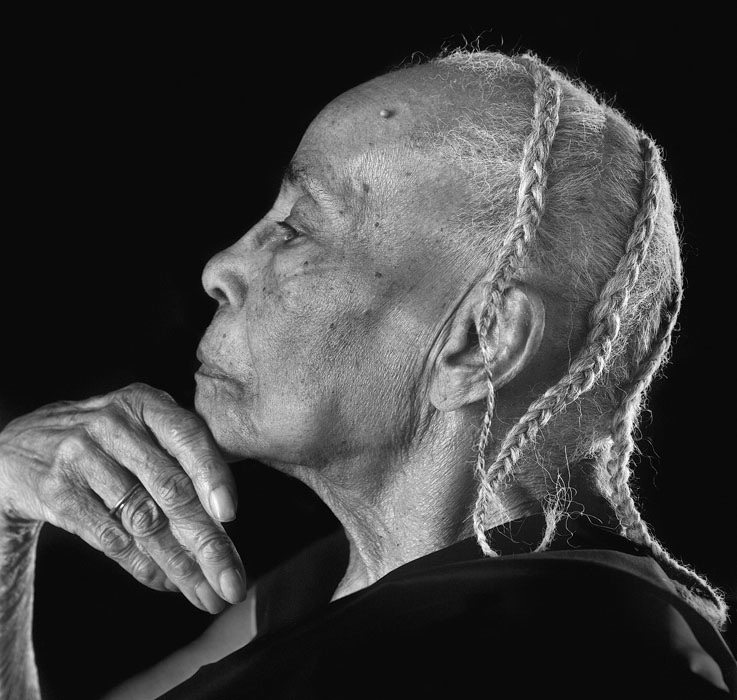

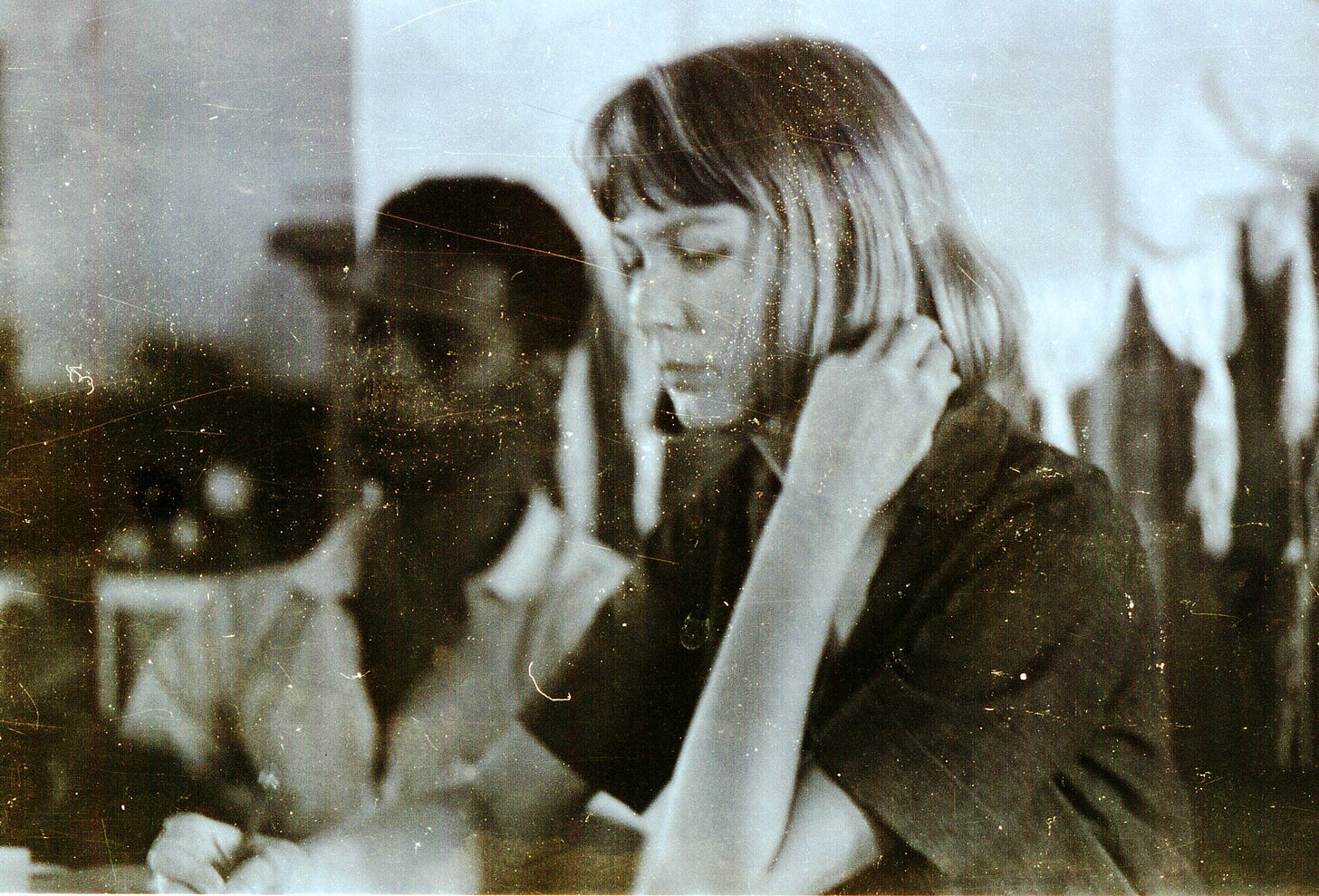

“You didn't see me on television, you didn't see news stories about me. The kind of role that I tried to play was to pick up pieces or put together pieces out of which I hoped organization might come. My theory is, strong people don't need strong leaders.”

—Ella Baker

Okay, we’re picking up rather abruptly where we left off.

The Prayer Pilgrimage was organized by . . . Bayard Rustin, A. Phillip Randolph, and a 53-year-old North Carolina NAACP branch director named Ella Baker, granddaughter of the farmers who raised her.

Often taken as a footnote in the Civil Rights Movement, Baker was, arguably, one of its strategic geniuses. She had worked with W.E.B. DuBois, with future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall who had won the school desegregation suit Brown v. Board of Education, A. Phillip Randolph, and Martin Luther King Jr. She also organized numerous voter registrations drives and trained future movement luminaries, Stokley Carmichael, Diane Nash, and Bob Moses. (Recommend Barbara Ransby’s biography, Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision.)

“There is . . . the danger in our [movement] culture,” said Baker, “that because a person is called upon to give public statements and is acclaimed by the establishment, such a person gets to the point of believing that he is the movement.”

This signaled the (class) tension between her and many of the rising figures within the SCLC, who were, by and large, petite-bourgeois male preachers near the top of local African American class hierarchies. King, Ralph Abernathy, Joseph Lowery, T.J. Jemison, Charles Kenzie Steele, Fred Shuttlesworth, and the rest of the male leadership were regarded in their communities almost as princes. A hint of the internal tension that pitted (arguably petite-bourgeois) respectability politics against a grittier and more practical approach to strategy was already evident when some of these leaders were scandalized by the combative and incredibly courageous Shuttlesworth raised funds by selling watermelons (rebuking his colleagues respectability fetish) and publicly dared the KKK to come after him.

Shuttlesworth ^^^ would eventually join Ella Baker as she organized the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), inspired in its tactical approach by the Greensboro lunch counter sit-ins. The SNCC became the motor of the most audacious (and self-sacrificing) element of the strategic nonviolence strategy. The SCLC and the SNCC worked together, sometimes fractiously, combining the former’s leader-centric methods with the mass-centric methods of the latter.

Baker and her colleague Septima Clark not only faced intra-racial class and strategy tensions, they were confronted constantly by plain, bog standard sexism.

“I can remember Reverend Abernathy asking many times, why was Septima Clark on the Executive Board of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference? And Dr. King would always say, ‘She was the one who proposed this citizenship education which is bringing to us not only money but a lot of people who will register and vote.’ And he asked that many times. It was hard for him to see a woman on that executive body.”

—Septima Clark

“See: I send you forth as sheep into the midst of wolves; so be as wise as serpents and a guileless as doves.

—Matthew 10:16

Meanwhile, the Chicago-based Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), under the direction of James Farmer, was organizing something called the Freedom Rides—again, taking their cue from Rustin’s 1947 (CORE) organization of the Journey of Reconciliation, which led to a Supreme Court decision that Southern states could not forcibly segregate interstate bus travelers, (Boynton v. Virginia, which led directly to the Freedom Rides).

James Farmer

CORE was joined by by the smaller SNCC. This tactic corresponded with Baker’s (and Randolph’s) orientation. (This is not to say that strategists were not often intellectuals. Baker and Randolph were both former valedictorians.) Farmer, on the other hand, arguably another of the movement’s strategic geniuses, “walked on two legs,” grassroots organizing combined with a ready-at-hand, high-level legal team and important liaisons with the powerful (Farmer was friends with Eleanor Roosevelt).

The 1961 CORE/SNCC Freedom Rides delivered the Civil Rights Movement’s next moral shock to the nation. Farmer, Baker, Clark, Randolph, Rustin, and the rest, opted for a multi-racial movement that would both shame the society at large and mobilize white allies, demonstrate cross-racial solidarity, and work as a ground-up organization that didn’t require high-profile charismatic leadership to function.

The Freedom Riders were multi-racial groups (mostly students) who rode interstate buses together through the deep South as a provocation to segregationists, by means of testing Boynton v. Virginia. Along their routes, they were met with mob and police violence and by arrests. Before we get into any details, though, let’s hover at high-altitude and examine the strategic background: the Cold War.

“I was not prepared for the happiness I see on every face in Moscow.”

—Paul Robeson

Paul Robeson, internationally acclaimed polymath (a professional athlete, singer, actor, lawyer, and socialist, who spoke English, Russian, French, Chinese, and Yiddish), was being feted around the Soviet Union and China, and even offered film roles by Soviet director Sergei Eisenstein. This, as Robeson had been blacklisted in the US. The US denunciations of the Soviet Union, with which it was competing for international influence, rang hollow on the international stage with Jim Crow still in effect. The Cold War is often ignored in accounts of the Civil Rights Movement; but it was the strategic context of this international rivalry that forced American elected officials, especially Presidents Kennedy and Johnson, to sign off on the bold legislative actions that would mark an end to legal Jim Crow. Without the Cold War, it’s doubtful whether the strategy of nonviolence or the decisive legislative actions it produced would have been successful at all. And Civil Rights leaders knew it.

By 1961, the public visibility of the movement had been fading, just as John F. Kennedy had taken office. The Freedom Riders aimed to bring the spotlight back.

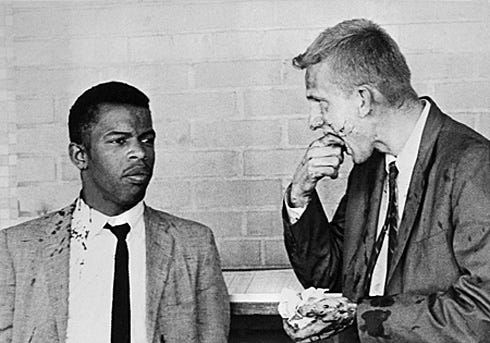

The first open attack on the Freedom Riders came on May 12th, in Rock Hill, South Carolina. Among the first casualties was a seminary student named John Lewis (who would come to chair the SNCC two years later, and eventually ascend to the US House of Representatives). Once in motion, the SCLC also offered its public support to the tactic.

On May 14th, the riders arrived at a bus stop in Anniston, Alabama, where they were greeted by a 200-plus white mob. The mob followed the bus as it departed, blowing out the tires, then firebombing the bus, whereupon they beat the fleeing passengers with bats and axe handles. The optics were horrible, and the incident gained national and international notoriety.

Fearful bus drivers refused to show up for work, and Attorney General Robert Kennedy intervened, putting police protection on the riders when they resumed on May 20th. The young SNCC organizer who got the buses moving again was Diane Nash, one of Ella Baker’s trainees.

The police, however, withdrew their protection between Birmingham and Montgomery, and the attacks resumed. A white mob in Montgomery laid into the riders with clubs and bats, forcing Kennedy to send in Federal Marshals.

Martin Luther King Jr., whose church was in Montgomery, led a service the next day for more than a thousand Freedom Ride supporters.

Robert Kennedy called for a “cooling off period,” to which James Farmer responded: “We have been cooling off for 350 years, and if we cooled off any more, we’d be in a deep freeze.”

Then, the Soviet Union issued a public denunciation of American racism.

By the time the Riders reached Jackson, Mississippi, they were greeted by a large crowd of supporters; whereupon the police arrested fifteen Riders for whites and blacks using the “wrong” designated restrooms. One of the arrestees was the 19-year-old future firebrand, Stokely Carmichael.

Freedom Rider mugshots taken upon arrest in Jackson, Mississippi

The rides and arrests continued into the Fall. The optics just got worse and worse, until the Kennedy administration forced the Interstate Commerce Commission to threaten bus companies with loss of licenses if they continued to segregate buses and bus stops.

I’ll interject here, to point out how different strategic orientations and tactical forms were effective when they matched the international and national context with the progress that each form, at each level, had achieved, whereupon the strategy had to be successively re-integrated. Grassroots/direct, symbolic/charismatic, legal, and political actions had to coordinate, through institutions, and correspond to dynamic contextual conditions. In an ideal world, this means leaders need to set aside their egos, and people need to employ organizations without fetishizing them, turning them into cults of personality to be used for personal gain. Nothing is ever ideal, but the closer a movement can come to this kind of agile and selfless strategic dynamism, the better its chance of success.

Enough said.

Looking at the further development of CORE, the SCLC, and SNCC, we’ll start with the Albany to Birmingham campaigns. The Albany (Georgia) Movement aimed to desegregate a city—a new tactical focus, led by SNCC activists Charles Sherrod, Cordell Reagon, and Charles Jones, who were already based in Albany for an SNCC voter registration campaign. Reagon’s wife-to-be, a fellow singer, Bernice Johnson, was also an organizer (see The Freedom Singers). The plan was initially opposed not only by tactically conservative balck leaders, but by the local NAACP—both of whom came on board as the campaign gained momentum.

Martin Luther king Jr. joined Albany and became, as one with ready-made notoriety—its public spokesman.

Cordell Reagon teaching nonviolence tactics, 1961

Long story short, the police merely arrested demonstrators, and, as the New Georgia Encyclopedia said, “In the end King ran out of willing marchers before Pritchett ran out of jail space. Once again King got himself arrested, and once again he was let go. By early August it was clear that King (sic) had proved ineffective in bringing about change in Albany.” The tactic failed, because the city simply ignored them, and the police refused to scandalize themselves with violence, settling on quiet arrest tactics.

NOTE: When we were organizing against George W. Bush’s neoconservative wars, many of us fell back on the movement tactics of yesteryear, i.e., massive demonstrations. They ultimately proved ineffective, precisely because the administration simply ignored us, as opposed to reacting. They “Albanyed” us. Only in our case, we lacked the institutional and strategic capacity to follow up, having abandoned concrete goal-directed actions for a series of performative actions. In our ignorance of thick histories, we believed “demonstrations” and symbolic action, on their own, were imbued with magical properties that would, like Joshua’s trumpets at Jericho, collapse the enemy’s fortress.

A personal backstory: I once worked very closely with Scott Douglas, the ex-Communist organizer of Greater Birmingham Ministries (it always goes back somehow to Alabama). Scott was (and probably still is) a veritable encyclopedia of Civil Rights apocrypha.

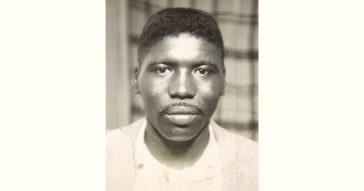

Scott Douglas

When he explained the Albany to Birmingham strategic transition to me, he said (paraphrasing badly from a long past conversation): “They wanted to draw a harsh response to their protests to mirror the moral effects of British violence toward Gandhi’s folks. In Albany [1961-2] they didn’t provoke anything that would mobilize sufficient outrage, so one of the Alabama organizers told Wyatt Walker, y’all move this thing to Birmingham. We have a dude down there named Bull Connor.”

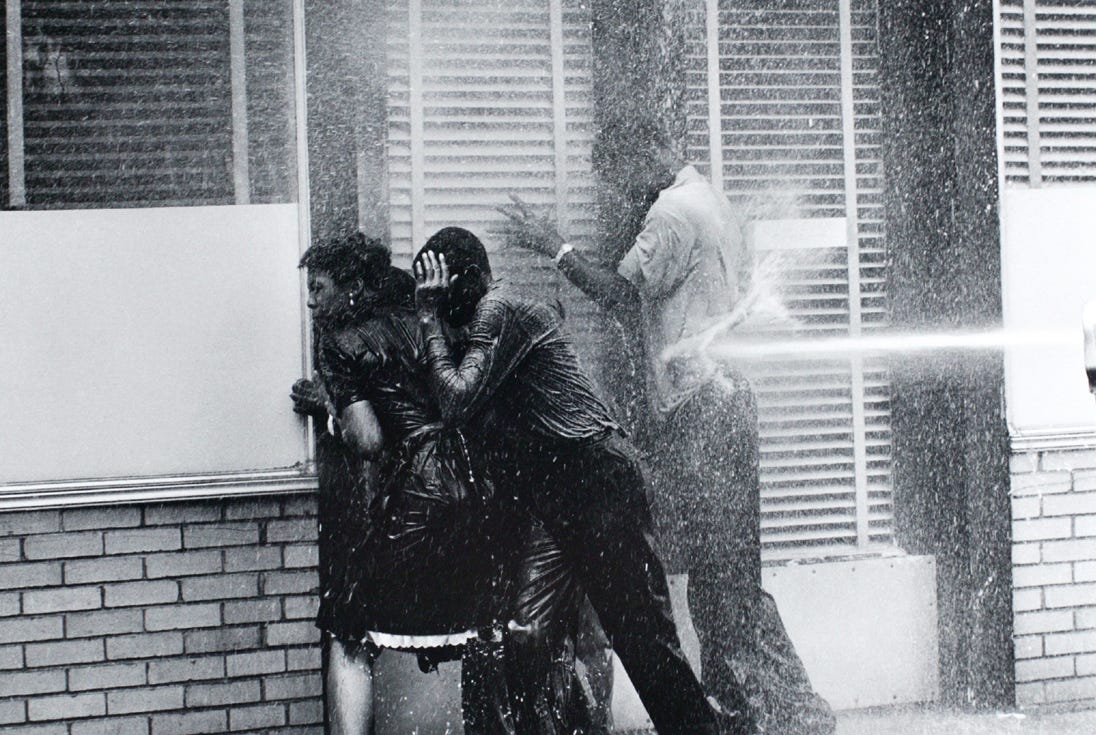

The public (tactical) goal of the Birmingham campaign (1963) was to desegregate downtown businesses. The strategic objective was, again, to realign the nation’s moral compass. Downtown business were targeted because Theophilus Eugene “Bull” Connor, rabid segregationist and former gubernatorial candidate, was Birmingham’s Commissioner for Public Safety. Black organizers who knew Connor by reputation and experience, counted on his macho fanaticism for a camera-worthy over-the-top response. Moral judo. They used Connor, and many sacrificed themselves before him.

Background: Between 1945 and 1962, there were more than fifty bombings directed at African American and African American institutions. None were investigated, and none were prosecuted. Among black people, Birmingham became known as “Bombingham.” One integrated neighborhood was bombed so often, it was called “Dynamite Hill.”

Birmingham was ripe for another reason. There was a split in public sentiment and in the city government. One one side were the hard-shell segregationists behind Connor; on the other, the white moderates who, while still segregationists, were concerned about Birmingham’s growing national infamy as a hotbed of violent white reaction. The latter group included the Chamber of Commerce, and in 1962, Connor’s faction lost the municipal election. Connor lost his bid for Mayor, but “retained” the office of Public Safety Commissioner, which exercised near absolute control over the police and fire departments. In a move that prefigured Donald Trump, Connor filed suit to prevent the new city government from taking office, and precipitated a kind of mini-Constitutional crisis for several months. It was during these tumultuous months that organizers launched the Birmingham Campaign.

The campaign had two thrusts. The first was the “selective buying campaign,” a targeted (and disciplined) boycott of downtown businesses, backed by demands for the desegregation of downtown enterprises (and several other peripheral demands, like opening public parks to blacks). The second was called “Project C”—the C standing for “confrontation.”

The best way to get a bad law repealed is to enforce it strictly.

—Wyatt Tee Walker

The chief strategist for Project C was Wyatt Tee Walker, a Petersburg, Virgnia pastor and founding member of CORE, and former Chariman of the A. Phillip Randolph Institute. (In September, 2015, Walker—still active—echoed Adolph Reed and others’ opposition to race reductionism.)

Walker had move to Atlanta in 1960, at Martin Luther King Jr.’s request to become the first Executive Director of the SCLC. His educational director was Dorothy Cotton, who would eventually join Septima Clark at the Highlander Center. In 1963, Walker and his top staff developed a highly detailed plan for the anticipated face-off with Bull Connor.

“My theory,” Walker explained, “was that if we mounted a strong nonviolent movement, the opposition would surely do something to attract the media, and in turn induce national sympathy and attention to the everyday segregated circumstance of a person living in the Deep South.”

The selective buying campaign, using a menu of tactics, ramped up the tension. When some business owners capitulated by taking down the “Whites Only/Colored Only” signs, Connor threatened to revoke their business licenses (using bogus fire inspections, among other things).

When Martin Luther King came on the scene, the timing of which was another tactical decision, the tension tightened further. King was, by then, a lightning rod for segregationist hatred. Native firebrand, Fred Shuttlesworth, denounced the city’s predictable reaction (an April 10 protest injunction that also raised bail 750%), further inflaming the unhinged Connor. Bail costs, however, drained the coffers of organizers, and King became increasingly anxious and indecisive about defying the injunction. The threat was palpable. Shuttleworth and other stiffened King’s resolve, and on Good Friday (April 12), King and fifty other organizers were arrested. It was then that King, undergoing a kind of transformation and acceptance of the possible fatal outcome of his continued actions, penned the famous Letter from a Birmingham Jail, chiding the white church (and white moderates) for their myopia, cowardice, and inaction.

The bail costs severely blunted the momentum of the campaign, whereupon James Bevel—a former cotton picker, steel worker, Navy veteran, seminarian, who’d trained at Highlander—committed to the most controversial (and ultimately effective) tactic of the campaign: The Children’s Crusade. (Later in life, Bevel went off the rails, falling in with LaRouchites and sexually abusing his daughters. He was imprisoned in 2008 for incest and child abuse.)

On May 2nd, thousands of students and young adults—from elementary school to college, many organized by 14-year-old Gwendolyn Sanders—walked out of their classrooms and took to the streets of Birmingham.

The students staged at Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, and from there left according to detailed plans (coordinating with walkie-talkies) to various target locations throughout the city.

Then came Connor.

Six hundred kids were arrested. Jails ran out of space, and Connor used a fairgrounds stockade to hold students. Then, in a fateful decision, he ordered the police and the fire department attack them with dogs and fire hoses.

In today’s parlance, we would say, the images went viral . . . internationally so. Soviet news flooded the globe with the story. Europeans were shocked. The whole African continent was outraged. And Birmingham, now a national and international pariah, was shut down. Protesters began setting off false fire alarms to draw off the fire department, and using “decoy” mini-demos to split the police, while larger groups then poured into target point businesses (an exercise of their tactical agility). Robert Kennedy prepared to send Federal troops. The cascade was on.

On May 8th, businesses capitulated to the movement’s demands. The AFL-CIO (now integrated) raised bail money. On May 13th, a bomb went off at the hotel where King had been only hours before, and two days later, three thousand Federal troops occupied Birmingham for the first time since Reconstruction. On May 21st, the court ruled against Connor, ejecting him from office. In June, all the public segregation signs in Birmingham were removed.

The breakthrough was accomplished, but it would come at a continuing price. On June 11th, President Kennedy announced that he would be pusuing comprehensive civil rights legislation. On June 12th, Mississippi NAACP officer and voter registration organizer, Medgar Evers, was shot dead in his own yard by fertilizer salesman and Klan member Byron De La Beckwith, in the third attempt on his life by local Klansmen since May 28th. Evers had attracted the ire of the local Klan by reopening the investigation of the lynching of 14-year-old Emmett Till in 1955.

Evers, a veteran of Normandy, was buried in Arlington Cemetery with full military honors. The ferociousness of Southern reaction after Birmingham cost many lives; but it only isolated the South further, and hastened ever stronger responses from Washington.

Meanwhile, on May 13th, A. Phillip Randolph—ever the labor organizer—announced plans for the “October Emancipation March on Washington for Jobs.” The intent was to further merge the civil rights movement with labor, and to shift emphasis, where possible, from racial to economic demands (which would have an outsized effect on African Americans). Initially, both the NAACP and the Urban League refused his invitation to join. The first buy-in, in fact, came from organized labor, i.e., the AFL-CIO. (There’s a Cold War element here, as well, but we’ll table it.)

By June, there was buy-in from James Farmer, Roy Wilkins, John Lewis, and Martin Luther King Jr. Together, they formed the Council for United Civil Rights Leadership (CUCRL). The NAACP and the Urban League were now in. Then came the National Council of Churches; the National Catholic Conference for Interracial Justice; and the American Jewish Congress.

There was internal tension over the question of direct action while in Washington after Kennedy expressed fear about it; but a compromise was reached that resulted in Kennedy’s endorsement of the action in mid-June.

Demands were as follows:

Passage of meaningful civil rights legislation;

Immediate elimination of school segregation (the Supreme Court had ruled that segregation of public schools was unconstitutional in 1954, in Brown v. Board of Education);

A program of public works, including job training, for the unemployed;

A Federal law prohibiting discrimination in public or private hiring;

A $2-an-hour minimum wage nationwide (equivalent to $20 in 2023);

Withholding Federal funds from programs that tolerate discrimination;

Enforcement of the 14th Amendment to the Constitution by reducing congressional representation from States that disenfranchise citizens;

A Fair Labor Standards Act broadened to include employment areas then excluded;

Authority for the Attorney General to institute injunctive suits when constitutional rights of citizens are violated. (link)

The march and demonstration were designed to consolidate gains, further isolate the opposition, and gather in greater mass support from those “on the fence.”

By March, there was a liaison appointed between event organizers and the Department of Justice. This incensed FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, with whom the Kennedys shared a tense relation and a strong mutual suspicion. Hoover was a devotee of the narrative that the entire Civil Rights Movement was some kind of Kremlin-inspired plot—a common claim by segregationists.

The final decision was to hold the demonstration on the National Mall on August 28th. The leaders all began receiving death threats, as did local leaders around the country who were recruiting and organizing buses. Participants-to-be were both terrified and resolved, and most had to dig deep in their nearly-empty pockets to pay for food, transportation, and lodging. Almost 21,000 police and troops were deployed in and around Washington.

The logistics rivaled a major military operation. How would the 100,000 expected people relieve themselves, deposit trash, get hold of a doctor?

On game day, hundreds of personal automobiles, 2,000 buses, 10 chartered passenger planes, and 21 chartered trains converged on DC and debarked a quarter of a million people—80 percent African American. The Mall was filled as various singers and twelve speakers appeared before he crowd and the transfixed national and international media, the last being the movement’s grand orateur, Dr. King, who would deliver his famous “I have a dream” speech. (The March was marred by the male leaders’ total exclusion of any women speakers, even though women had been at the forefront of the struggle from the outset.)

It was, by any measure, a success. President John F. Kennedy would say afterwards, “The Civil Rights Movement should thank God for Bull Connor. He’s helped it as much as Abraham Lincoln.” Moral judo.

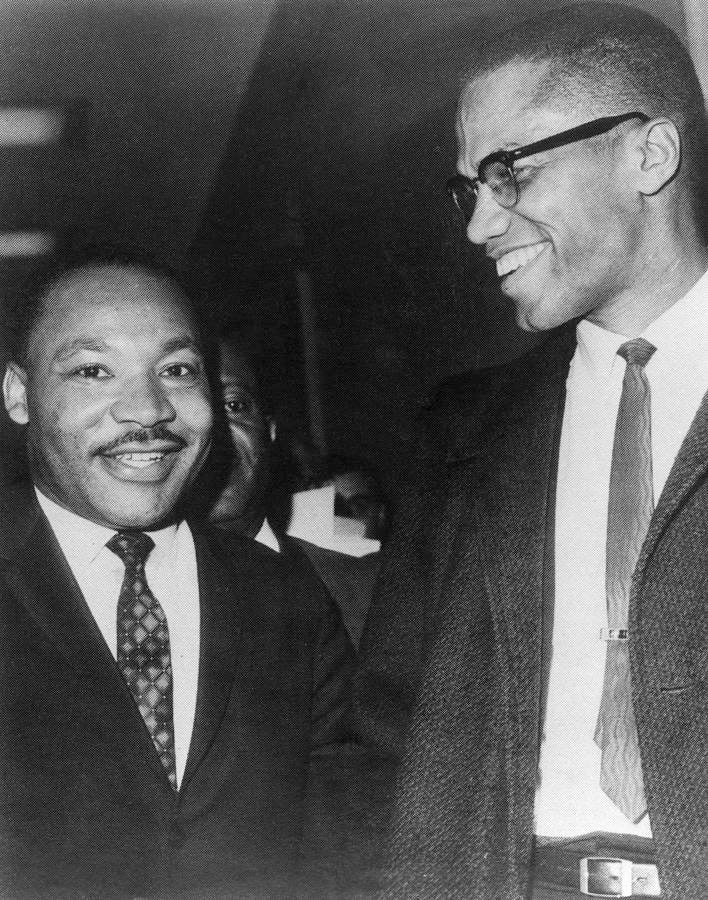

But fractures were already opening. Malcolm X, formerly Malcolm Little, a black nationalist follower of Elijah Muhammad and his Nation of Islam (NOI), was an ever larger presence on the national stage. He denounced the march because of white participation. Many of the younger members of the SNCC, rankling now at the slow pace of progress and even at nonviolence, had begun to move in his direction.

Until his break with the NOI in 1964, Malcolm X subscribed to its beliefs, which counted white people as devils and predicted the immanent destruction of the “white” race. By 1963, Malcolm was living in tension with these beliefs, though he remained convinced that black people needed to separate from “white” society.

There was a seldom remarked demographic split between Malcolm and other separatists, both in region and religion. The Civil Rights Movement was Southern-centric and led by Christians, whereas separatism was finding more fertile ground in Northern cities and increasingly rejected Christianity as a “white” religion. (Among separatists there was also a strong current of antisemitism, whereas the Civil Rights Movement was supported by substantial numbers of American Jews.)

Meanwhile, Kennedy had already proposed what would become the Civil Rights Act of 1964; but after the March, two things happened in succession.

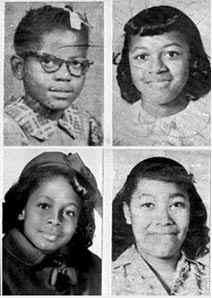

First, on September 15th, the Klan bombed the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, killing Addie Mae Collins (14), Cynthia Wesley (14), Carole Robertson (14), and Carol Denise McNair (11), and injuring twenty others.

After the blast, more than 2,000 enraged and grief-stricken African Americans flooded the scene. Fights between groups of black and white youths broke out in streets across the state. Then riots. Businesses were fire-bombed. 16-year-old African American Johnny Robinson and 13-year-old Virgil Ware were both fatally shot, Robinson by the Birmingham Police, and Ware by a suburban 16-year-old named Larry Sims. Many blamed Governor George Wallace, who had days before said the defense of segregation required more funerals.

The second thing that happened after the march was the assassination of President Kennedy on November 22nd in Dallas, Texas.

Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson was sworn in the same day. A new political realignment, unrecognized at the time, had begun. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act in 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

(Jumping ahead before we continue, these laws, signed by Democrats—the former party of white supremacy—set the stage for what would become Nixon’s 1968 “Southern Strategy,” which converted the South to the Republican Party—a change that persists today. The Republican Party would become, in the United States, the political refuge for white supremacists, both overt and coded. This is not to say that all Republicans are racists—and there are non-white Republicans—but to say that nearly all remaining white supremacists still vote Republican.)

By 1964, the SNCC was a growing political force, having undergone the Leesburg Stockade, organizing Freedom Summer, and launching multi-racial voter registration drives. It was during one of those drives, on July 21st, in Mississippi, that James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner were murdered by the Klan, Cheney was black, and the other two were Jewish. Freedom Summer jumped into the national and international headlines.

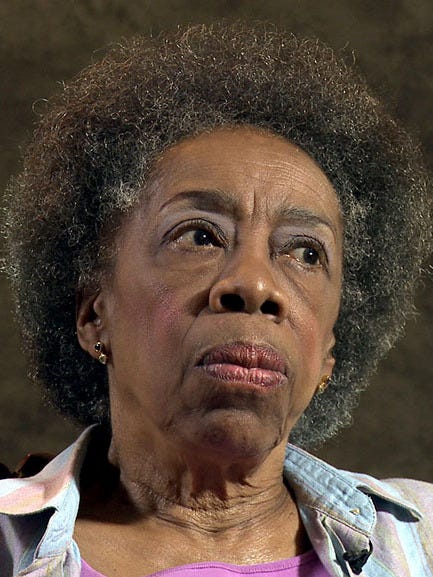

At the same time, the SNCC was organizing the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP), the Vice-Chair of which was an ex-cotton-picker named Fannie Lou Hamer.

The MFDP was designed to grow a Black Democratic organization parallel to the all-white DP in Mississippi, and seek representation at the national level—a bold and innovative strategy. At the National Convention, where Hamer spoke (and her speech garnered media attention), Johnson offered two seats to the MFDP, to which the firebrand Hamer replied:

All of this is on account we want to register, to become first-class citizens, and if the Freedom Democratic Party is not seated now, I question America. Is this America, the land of the free and the home of the brave, where we have to sleep with our telephones off the hooks because our lives are threatened daily because we want to live as decent human beings in America? … We didn’t come all the way up here to compromise for no more than we’d gotten here. We didn't come all this way for no two seats when all of us is tired.

. . . provoking the white Mississippi delegation to walkout of the convention.

In 1968, the Party would accede to Hamer’s demands.

In the meantime, still in 1964, there was an election coming. Johnson was being challenged by Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater (Seventeen-year-old Hillary Clinton worked that year on the campaign as a “Goldwater Girl.”) And Alabama’s Governor George Wallace mounted a third-party campaign. Between Goldwater’s conservatism (and opposition to the Civil Rights Act) and Wallace’s abandonment of the Democrats, the stage was set for a Nixon victory four years later.

A three-way split was forming inside the SNCC, with some members opposing participation by Communists and the leftist National Lawyers Guild, other’s defending their participation, and a “black power” current impatient with nonviolence and white activists.

“When you are in Mississippi, the rest of America doesn’t seem real; and when you are in the rest of America, Mississippi doesn’t seem real.”

—Bob Moses

Dilution of the Southern vote by Goldwater and Wallace led Johnson to a landslide victory. When he was sworn in again in 1965, the SNCC was already fighting itself.

The impatience with nonviolence was understandable, if not justifiable. Violence against black people, activists, and the SNCC itself had escalated dramatically. Sandra “Casey” Cason, an Ella Baker hire and white SNCC member, said, “We’re reeling from the violence.”

Radical singer Nina Simone wrote and sang, “Mississippi Goddam.”

“At the summer’s end,” reported Julian Bond, “three project workers had been killed; four people had been critically wounded; and 80 workers had been beaten. There had been over 1,000 arrests; 35 shooting incidents, 37 churches bombed or burned; and 30 black businesses or homes burned.”

The nascent “militant” faction brought with it a kind of macho vibe, that translated into more pronounced intra-movement sexism. Cason would write,

There seem to be many parallels that can be drawn between treatment of Negroes and treatment of women in our society as a whole. But in particular, women we’ve talked to who work in the movement seem to be caught up in a common-law caste system that operates, sometimes subtly, forcing them to work around or outside hierarchical structures of power which may exclude them. Women seem to be placed in the same position of assumed subordination in personal situations too. It is a caste system which, at its worst, uses and exploits women.

In 1966, Stokely Carmichael would infamously say, “the only position for women in SNCC is prone,” a grotesque gaff of which he would later repent.

Book recommendations: Clayborne Carson’s In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s, and Howard Zinn’s SNCC: The New Abolitionists.

These fault lines overlaid the longer-term division epitomized by the Ella Baker/Martin Luther King Jr. differences between the grassroots and “messianic leader” orientations. King was being sidelined, as a new generation of public leaders came to the fore. These differences were overcome, one last time in 1965, with the Selma to Montgomery marches.

Alabama, like other states, refused to comply with the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Voter registration drives, as well as integration sit-ins and demonstrations continued to be met with arrests, beatings, and murders. In late 1964, the SNCC and the Dallas County (Alabama) Voters League (DCVL) invited King’s SCLC (because of his visibility and moral authority) to assist. The target was to be Selma, the county seat, where the SNCC and DCVL already had many activists on the ground. Selma had imposed a public assembly injunction on any gathering of more than three people involving civil rights activity.

(The film Selma came out in 2014, and reader may want to see it, in spite of its manifold historical inaccuracies and sometimes ridiculous portrayals of the people involved. I recommend Adolph Reed’s critique of the film as an accompaniment, which makes references to some of the subjects we’ve covered above—Reconstruction, Fusion, etc. Reed quipped that Rustin’s absurd portrayal made him look like a gay party planner.)

Beginning in January 1965, the SCLC, SNCC, and DCVL demonstrated in violation of the injunction. In the background was division between Selma’s Mayor, Joseph Smitherman and Dallas County Sheriff Jim Clark.

Smitherman was a “moderate” segregationist, looking to attract Northern business to Selma, who wanted to follow the Albany reaction strategy of quietly absorbing the protests. Clark, who liked to dress up in military attire and carried a cattle prod with his gun, was a hard-boiled racist, with a real taste for violence. Clark commanded a local militia composed of Klansmen among others, and they went about on horseback with guns, whips, and cattle prods like their commander. He continually used his militia to challenge Smitherman’s jurisdiction, even inside the city limits of Selma.

In January 1965, the Civil Rights organizations held a mass meeting at Brown Chapel AME Church, defying the injunction. Clark was out of state, and Smitherman ignored the injunction, letting the meeting go unobstructed. A massive voter registration drive was planned, as King coordinated with President Johnson, the latter agreeing to accelerate efforts to pass voting rights legislation.

In mid-January, when Clark returned, the arrests began afresh. On January 22nd, a large group of black teachers assembled at the Courthouse to register. Many were carrying toothbrushes aloft as a sign of their willingness to be jailed. Clark’s men waded into them with cattle prods and truncheons. The bloodied teachers regrouped and went forward again, and were beaten back yet again. Only after a third time did they retreat. The optics for Clark and Selma were horrible, and the Teacher’s March was greeted with accolades from blacks (and many white allies) across the country.

Sheyann Webb, who was 9-years-old at the time, would write:

Most of us had viewed the educators as stodgy old people, classic examples of true “Uncle Toms.” But that wasn't the opinion that day. I looked about me and saw scores of other children running about the [Carver Housing Project] shouting the news that Mr. Somebody or Old Mrs. Somebody was marching. Could you believe it?

Some little boys came running down the street yelling that they were coming back. Me and Rachel [West] went into the church which was packed with people. We waited and when the teachers began coming in everybody in there just stood up and applauded. Then somebody started to sing ... first one song and then another, as they walked in. And they were all smiling; kids were shaking hands with their teachers and hugging them. I had never seen anything like that before ...

Some of the women teachers were crying, they were so elated. Mrs. Bright spotted me, and rushed forward, hugging me. She appeared to be in a mood of triumph. She laughed, she wiped at her eyes, she hugged me again. I remember she said something about her feet being tired, and I said, “You did real good.”

“I try to be nonviolent, but I just can’t say I wouldn’t do the same thing all over again if they treat me brutish like they did this time.”

—Annie Lee Cooper

On January 25th, Clark used a baton to jab a combative activist named Annie Lee Cooper in the neck. Cooper’s courage—as evidenced in the past—was comparable to Fred Shuttlesworth. She had tangled with Clark before, when she rushed to defend one of his victims from the clubs. In an instant reaction to the jab in the neck, the stout 53-year-old Cooper, in the vernacular of my own past, knocked the cowboy shit out of Clark, then leapt on top of him after he fell to give him some more. It took several deputies to pull her off. While she was in jail, she sang hymns. In spite of her violation of the principles of nonviolence, she became a legend.

Some teachers it’s best not to mess with.

Clark’s actions, the Teacher’s March, and the Cooper incident were building toward something. Solidarity demonstrations were mounted across the country. On February 4th, President Johnson gave an address supporting the Selma campaign. It was then that the first glimmering of some kind of tense coordination between Malcolm X and the nationalists and the nonviolent movement, as Malcolm saw the momentum building in Selma.

The idea was to counterpose King’s nonviolence as the carrot and Malcolm X’s declaration of “by any means necessary” as the stick. After months of organizing, and even winning over many around the country, only about 300 additional black people were added to the list of registered voters. The movement need a kick-start.

On February 18th, in neighboring Perry County, a violent criminal named James Bonard Folwer, who had become an Alabama State Trooper, followed Civil Rights activist Jimmie Leee Jackson into a cafe and shot him. Jackson died on February 26th.

The shooting ignited demonstrations in Dallas County and neighboring Perry, Wilcox, Hale, and Loundes Counties; and the demonstrations were met, yet again, with brutality from police and mobs. One demonstration of around 400 people, protesting the bogus arrest of popular local organizer James Orange, was clubbed down by white mobs, who turned their rage on reporters and attacked them, too.

After the speeches we decided to have a short march to the courthouse to protest the arrest of our co-worker, James Orange. We filed out, and turned toward the courthouse. The cameras were shooting. All of a sudden we heard cameras being broken and newsmen being hit. I saw people running out of the church. ... The troopers were in there beating folks while local police were outside beating anyone who came out the door. ... A big white fella came up to me and stuck a double-barreled shotgun, cocked, in my stomach. “You’re the nigger from Atlanta, aren’t you? Somebody wants to see you,” he said, and he took me across the street to this guy with a badge and red suspenders and chewing tobacco. “See what you caused,” he said, and he spun me around, “I want you to watch this.” There were people running over each other and trying to protect themselves.

One guy was running toward us. When he saw the cops he tried to make a U-turn and he ran into a local cop. They just hit him in the head and bust his head wide open. Blood spewed all over and he fell. When I tried to go to him, the sheriff pulled me back and stuck a .38 snubnose in my mouth. He cocked the hammer back and said, “What I really need to do is blow your God damned brains out, nigger.” ... I was scared to death! He said, “Take this nigger to jail.” So they took me, and they hit me all over the arms and legs and thighs and chin. There were others there got beaten the same. ... There were literally puddles of blood leading all the way up the stairs to the jail cell.— Willie Bolden

Between February 18th, when Jackson was shot, and the 26th when he died, Malcom X—who had broken from Elijah Muhammad over Muhammad’s sexual incontinence—was assassinated in February 21st.

These two killings provoked anger . . . and despair. Everywhere, meetings were disrupted by Klansmen and armed members of the White Citizens Council.

James Bevel, voting rights coordinator for the Selma SCLC, approached King with the notion of a march from Selma to Montgomery, the state capital, to confront Governor George Wallace. King was miserably sick with a virus, but he still managed to make a statement:

He was murdered by the brutality of every sheriff who practiced lawlessness in the name of law. He was murdered by the irresponsibility of every politician from governors on down who has fed his constituents the stale bread of hatred and the spoiled meat of racism. He was murdered by the timidity of a federal government that is willing to spend millions of dollars a day to defend freedom in Vietnam but cannot protect the rights of its citizens at home. ... And he was murdered by the cowardice of every Negro who passively accepts the evils of segregation and stands on the sidelines in the struggle for justice.

The SNCC opposed the Selma to Montgomery idea, calling it “dangerous grandstanding.” Governor Wallace warned marchers that he would not tolerate it.

On March 6th, Selma was surprised by a “white march” in solidarity with King, organized by a Birmingham Lutheran pastor, Joseph Ellwanger.

Ellwanger’s demonstrators were met by armed white mobs, and had to be extricated by Selma’s Police Chief, Wilson Baker. The planned Selma to Montgomery march was the next day. Sheriff Jim Clark, meanwhile, was organizing his response.

The plan was for 400 marchers, but more than 600 showed, including dissident members of the SNCC. King was still ill, and the march was led by Hosea Williams. Baker’s deputies, assisted by state troopers, were standing by with 200 men in uniform. Local white gangs loitered menacingly along the initial route. Baker’s armed phalanx was positioned just across the Edmund Pettus Bridge over the Alabama River.

We kept stepping two by two, one foot in front of the other one, marching resolutely into hell, because it was so clear that we were going to be beaten. I mean, these men were just so prepared, they were not going to let their readiness go to waste by not beating us. I mean, when you look back on it, it was very clear.

— Charles Bonner, SNCC

The only tactic for the march was to meet any confrontation, no matter how violent, by kneeling to pray.

Hosea Williams (LF) flanked by John Lewis (RF). As they had crossed, Williams had looked down at the river and asked Lewis, “Can you swim?” Lewis, said, “No.” Williams replied, “Neither can I, but we might have to.”

As the front ranks reached the other side of the bridge, troopers ordered them to halt. The entire file of 600-plus knelt in prayer.

Deputies, troopers, and posse-men—some on horseback—fell savagely on the file of marchers with tear gas, clubs, whips, pipes, and chains, in what would come to be known as Bloody Sunday.

The violence momentarily reforged solidarity between the SNCC and the SCLC.

A second march was planned for the following Tuesday, for which King reached out and assembled more than 3,000 people, including a very substantial number of Northerners and white people (up to one-third white).

Again, since strategy is our theme, and this period is absolutely pivotal, we need to preface the events of the “Tuesday Turnaround” with a good deal of strategic context.

President Johnson responded to Bloody Sunday with a vow to pass the Voting Rights Act as soon as humanly possible. Meanwhile, Kennedy’s assassination had left Johnson holding the bag of Vietnam. The Viet Minh (called Viet Cong by their enemies) and the North Vietnamese Army were trouncing the South Vietnamese government, politically and militarily. On Monday, after Bloody Sunday, US Marines landed in Da Nang. The US was rapidly escalating its participation and in the same month had begun the infamous “Rolling Thunder” bombing campaign that slaughtered around 25,000 people, 15,000 of them civilians. Along with germinating war opposition at home, the violence in the South was eroding the administration’s credibility among its own supporters, and further destroying American credibility abroad. Marches were springing up all over the country. 700 showed up at the White House. Johnson—looking for some breathing space—begged organizers not to follow with another demonstration. The SCLC petitioned District Court Judge Frank Minis Johnson to prohibit state interference (Williams v. Wallace), but Judge Johnson (quite possibly after receiving a call from President Johnson) instead issues an injunction against the march. This placed the SCLC et al on the horns of a dilemma. President Johnson is the key to the strategic goal of passing the Voting Rights Act, but acceding to a clearly unconstitutional injunction will blunt momentum, split the movement, and damage the leadership’s credibility.

Through spokesmen, President Johnson sends a promise from Washington that he will support new, strong voting rights legislation. But his surrogates also warn King that if he marches on Tuesday, LBJ may weaken—or possibly oppose—a new voting rights bill. Even with the President behind it, a voting bill has to overcome a southern filibuster to pass in the Senate. That filibuster cannot be broken without the votes of Republican senators. Republicans, and particularly their leader Everett Dirksen, are strong for “law and order.” They are already uncomfortable with Blacks disobeying local segregation ordinances and police commands; they might well view breaking a federal injunction as defiance of their own national authority (and so too might some northern Democrats). Even if Tuesday’s march wins through to Montgomery—which no one believes is possible—doing so at the cost of eventual defeat in the Senate is a disaster, not a victory. And despite Judge Johnson’s political stab in the back, confidence remains high that he will eventually rule in favor of the Freedom Movement's right to march to Montgomery. (Civil Rights Movement Archive)

King secretly coordinated with President Johnson, using an intermediary, to do a symbolic “turnaround,” even as more than 900 Northerners, black and white, with a few Asians and Latinos, were showing up prepared for beatings, arrests, even martyrdom.

They had seen the news and left home before the broadcast officially ended for the evening. I saw new life leap into the faces of the people and they were ready to sacrifice more. During the next 48 hours, hundreds and hundreds of people from heaven knows how many different states in the Union came to Selma. Black families opened their homes and gave their beds to people who had come to Selma. ... Local residents opened their homes and travelers from afar accepted the warm embrace and kindness that was extended. The only phrase a newcomer to Selma had to utter was, “I am here to march.” That phrase secured the speaker a home, a bed, and food with no questions asked.

— Rev. F.D. Reese

The Klan, the cops, the Clark militia, and the White Citizens Council were preparing, too, with a special hatred for those they called “white niggers.”

The Medical Committee for Human Rights established emergency aid stations.

Meanwhile, King had told none of them of his plan to turn around at the bridge, even as marchers sang “Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me ‘Round.”

Personal excursus on Gwen Patton and Charles “Chuck” Fager: I met Gwen in 1996, and worked with (and for) her off and on for the next four and a half years (at the same time I worked with (and for) Scott Douglas. (Our first meeting together was at the Highlander Center.) Both of them were my kind and patient teachers, as I was just dipping my toe into politics after a career in the Army. My first personal meeting with Gwen was in her little home in Montgomery. We had coffee and talked politics in a book-cramped living room, the walls yellowed by the unfiltered Camels she smoked. She was a gracious woman, who was nonetheless fierce in her sometimes heterodox convictions. No one came in for sharper criticism from her than the black political class, as I observed on one memorable occasion, when she confronted a younger man flogging black entrepreneurialism, who tried to put her in place by saying, “We didn’t come all this way to be poor.” Long story short, he learned a valuable lesson that day, and not a pleasant one.

Chuck Fager I met (and worked closely with on occasion) while organizing against Bush fils’ sanguinary Middle Eastern war. Chuck was (and remains) a Quaker, and at the time, he was running the Quaker House in Fayetteville, North Carolina, where he supported conscientious objectors, AWOLs, and veterans who had turned against war. It was while working with Chuck—from whom I learned a very great deal—that I was confronted with the youthful arrogance of some of the pop-poststructuralist “activists” from nearby universities, who denounced him on the basis of (1) his age, (2) his being white, and (3) his impatience with their relentless “call-out” culture, which he rightly identified as insider virtue-signaling.

During Selma, when they were thrashing it out on the front lines, I was thirteen-years-old. Gwen and Chuck extended their activism into opposition to the Vietnam War—a controversial move within the Civil Rights movement, and one that, when taken up by King himself in a couple more years, would lead to his abandonment by many white liberals (and indirectly to his death).

Recommendation: The PBS television series, Eyes on the Prize.

Another excursus here. We’ve been reviewing events, but our intent is not to focus on the events in isolation, or as landmarks in history, even if any review like this will inevitably default to that in some degree. I want to remind and reiterate to readers that events are the last act in a very dynamic, labor-intensive, intellectually demanding, emotionally draining, inter-personally difficult, planned-and-replanned, intricately coordinated process, involving tired, often testy, oftentimes ego-driven, faulty human beings with contradictory public and personal, agendas, who, like us all, were driven by bewildering psychological desires.

For these reasons, taken as a whole greater than its parts, we can reasonably discern the strengths and weaknesses of the two sides of the strategic “grassroots/charismatic leader” dichotomy, which I’ll argue is false, inasmuch as each aspect tends to be fetishized, or abstracted, into an unnecessary, even destructive, antagonism with the other. In fact, both social movements and their compositional events demand a dialectical, even multilectical, integration. This is a simple, almost Pauline, claim. As the communion hymn goes, “there are many parts, they are all one body.”

Latent strength comes from the grassroots, focus is attained through a singular leader and goal, coordination requires institutions, and the teleological objective has to be a single event (an election, e.g.) or demand (the vote, e.g. . . . “eyes on the prize”). In somewhat archaic military terms, there are four levels of consideration: (1) strategic objectives, (2) facilitating campaigns, (3) “battlefield” tactics, and (4) skills/techniques. You train from the bottom (skills/techniques) and plan from the top (strategic objectives). Because the context is always shifting, and because the forces of antagonism are themselves flexible conscious actors, leadership itself requires what might be called timely intelligence (information dispassionately analyzed and organized in such a way as to make educated guesses about contextual shifts and the likely actions and reactions of “the other side(s),” . . . and the creativity and agility to retain the initiative (the ability to initiate, as opposed to react) without deviating from or undermining the main strategic focus.

Furthermore, and speaking more concretely, mass is never generated by sloganeering, propaganda, or ideology. That comes later, from those who want to exploit the context. The psychological basis of mass is common experience, which, historically speaking, is only mobilized by a sufficiently intolerable intensity of fear, misery, loss, and repression. This is the ground of context. Secure, comfortable people do not take to the streets. Which is not to say that your fear and my fear are the same thing. Misery and repression are experienced together by “lower” classes; but among those with more, there is more to lose—whether that’s status, security, or money (often part of the same package). Reactionary movements, for example, are more of an insecure middle class phenomenon—people who have something to lose.

At the strategic, campaign, and tactical levels, almost every earlier form of movement organization has been rendered obsolete by the digital revolution. Not only has this changed communication and shifted the power of the ruling stratum, it has enclosed, atomized, and isolated people to a staggering degree.

Geoff Schullenberger gave an apt description of this shift as “viral hegemony.”

“Viral hegemony,” he explains, “is arrived at not through a ‘long march through the institutions,’ but a rapid stampede across the algorithmically mediated public sphere, which the logic of the attention economy tends to push far more rapidly into cycles of extremist one-upmanship.”

We’ll return to this further on, when I include in this rough formula . . . luck.

History that hasn’t been chipped and polished into iconography gives the lie to any such thing as The African American . . . a more recent iteration of The Negro, when DuBois, Garvey, and Washington were duking it out at the turn of the last century. At least they were in a time when the depredations of having been racialized were so stark and dangerous that unity of experience provided the basis for a common identity. But as the fights of the aforementioned demonstrate, even a strong unity of experience doesn’t necessarily translate into a unified strategic orientation (and class stratification differentiates strategic objectives). The rift between Martin and Malcolm was yet another example, as was the tension between the SCLC and the SNCC, as is the apparent paradox today of Trump receiving the largest share of “the” black vote of any Republican for the last century (a demonstration surely of the differences in experience between black men and black women, or men and women more generally). I’m a former Marxist and a current Christian. If you want to see some acrimonious fights, check out either history. The article “the” is in itself a distortion, a hyper-abstraction, of reality, and useful as hell to the dominant order. One reason the NGO/PMC “left” has been so successful in its service to the dominant class is that it’s convinced people of the existence of fictional (or, online . . . same thing) “communities” in such a way that real political agency has been supplanted by imaginary agency, and “members” of these “communities” are willingly siloed into online semiotic tribes, with neither class consciousness nor any political capacity except to constantly brain-drain challenges to that dominant class. The very idea of including the billionaire Oprah Winfrey in some reification called a “marginalized community” is ludicrous.

The major error of the Millennial left that formed around the 2016 Bernie Sanders campaign was combining “socialism,” which they could have more productively just called “social democracy,” with this pop-academic tic about “marginalized identities,” and placed the emphasis (employing a form of message discipline that the right had mastered, and of which the “left” proved incapable) on the universality of economic solutions (Medicare For All, Federal jobs guarantees, scrapping the cap on Social Security, raising the minimum wage, etc.). Unfortunately, the Democratic Party was able to use this urban/grad degree tic against them (along with tsunamis of money and the able assistance of the black political class); but what they lost was the possibility of overcoming Democratic resistance by recruiting far larger numbers of “independent” voters.

Returning, then, to Selma, Turnaround Tuesday was King’s worst organizational blunder. An old organizer once told me, “You win trust by the teaspoon and lose it by the bucket.” King gobsmacked his followers by standing down at the Edmund Pettus Bridge on March 9th, even as troopers stood aside to let them pass.

Strategically and tactically, turning around was probably the right decision. Compartmentalizing then decision to do so in one man, and failing to share it with other leaders or any of the rank and file, was disastrous to King’s credibility inside the movement, exposing him and the movement more generally to the influence of younger, more macho, more separatist trends that had been percolating for some time. James Foreman called the move “trickery against the people.”

Foreman and the SNCC decamped to The Tuskegee Institute to join Gwen Patton and Sammy Younge (who would later be murdered, as well), where they organized a march to Montgomery to confront Governor Wallace. This precipitated a struggle between Foreman and Bevel, as Forman was resorting to very more violent language.

Sympathy marches sprang up across the country, and a beleaguered President Johnson worked on the final draft of the Voting Rights Act which he introduced to Congress on March 17th, the same day the court ruled for the protesters in Williams v. Wallace. The Selma to Montgomery March was on again.

Follow-on actions and reactions filled the calendar between March 24th, when more than 25,000 people arrived in Montgomery, and August 6th, when Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

PART 3—coming soon