I fucking hate you! Motherfucker!

Motherfucker! I fucking hate you! Fuck you!

You son of a bitch, you fucking ruined my life!

I wanted to die!

I'm sick of it, motherfucker... oh, oh

Why'd you fuckin' do it to me?

—Korn, “Daddy”

We left off in the last installment with African American Atlanta Mayor Andrew Young in 1977 sending black-and-white cops to break the strike of mostly-black sanitation workers. Once friend and confidant to Martin Luther King Jr. and former head of the SCLC, Young would go from being Mayor of “the jewel of the New South” to US Ambassador to the United Nations under President Jimmy Carter. And it is with the Carter administration that we’ll begin again . . . but first, a personal reflection.

As I write this, we’re all dealing with the second Presidency of the postmodern Caligula, Donald Trump. Trump is seriously planning—in my view—to annex Greenland, by force if necessary; and his moves on this account correspond to an abrupt and vandalous break with the Eurozone. I’ve made from-my-basement Olympian remarks about how this marks the end of the Post-WWII world order. My friend, Charlie Collier, responded (referring to our mutual theological mentor), “I talked to Stanley [Hauerwas] on the phone a couple of weeks ago, and he said something along the lines of it being impossible to know what Trump 2.0 will ultimately mean, but it could spell the end of the post-Westphalian order.” Stanley’s Olympian perch is apparently at a higher altitude than my own.

(I’m no fan of NATO or the neoliberal world order, but I’m with Joe Kenehan of Matewan, who warned striking miners, “Fellas, we’re in a hole full of coal gas here. The tiniest spark at the wrong time is going to be the end of us. So we got to pick away at this situation, slow and careful.” You don’t just burn everything to the ground without a thought for the people in the buildings.)

History always tells a different story, not only from the standpoint of the teller, but based on where one chooses to chalk the starting line. In the last installment, I made much of Nixon’s likewise abrupt (and equally beggar-thy-neighbor) exit from Bretton Woods (an arcane point to some), wherein abandoning an international currency regime set the stage for the neoliberal era that came off the blocks during Reagan’s presidency.

The reason—again—that any study of political strategy requires history is that strategy is always and inevitably contextual. The problem, from a study point of view, is that past contexts in themselves were infinitely complex, which leaves a lot of speculative space between the atoms, so to speak.

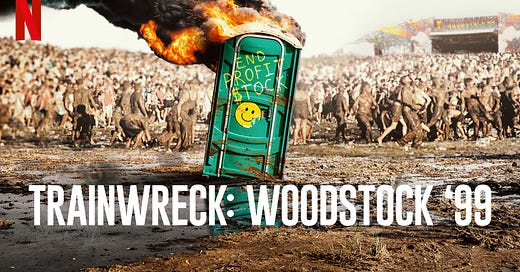

I recently watched a documentary, Trainwreck: Woodstock '99, about an abortion of an attempt to reproduce Woodstock, the music festival of 1969, the year I barely graduated from St. Charles High School in Missouri, and the year before I joined the Army in January 1970.

I’m not going to romanticize Woodstock (the original), or the era, but things changed, a lot, between 1969 and 1999. As to context.

And as to analogy, we mentioned in earlier installments how some of us tried to reproduce Civil Rights style demonstrations in 2002-3 against the Bush fils administration’s warmongering. We turned out more people, nationally and internationally than the Civil Rights organizers could ever have fantasized. Nonetheless, we accomplished . . . jack shit. The “Global War on Terror” went forward into its disastrous and self-inflicted denouement.

What were the differences between Woodstock 69 and Woodstock 99? Let’s begin with the zeitgeist, to which I can speak personally, even though my own peculiar upbringing was a bit out of tune with things then. Yes, it was a time of turmoil, but all turmoil is not the same. Every period is determined to a substantial degree by what I’ll call inter-generational drift. This is simultaneously sociological and phenomenological—politico-economic, cultural, psychological (and yes, spiritual).

After Vietnam, I was assigned to the 82nd Airborne Division in Fort Bragg, North Carolina. In 1972, just before my first of three ETS’s, I heard a retired General who’d served in World War II reflect with a certain confusion, grief, and even anxiety about the differences he observed between men returning from WWII and Vietnam.

Returnees from WWII still held—however imperfectly—to a world of meaning and purpose, and most of the white ones settled gratefully into the stable peacetime norms of work, home, and family. The war they’d fought made sense to them.

Vietnam returnees, the old General said, were different. Our war was both unpopular and meaningless, and we experienced the war as something far more nihilistic (we didn’t refer to battle victories, but body counts). At the same time, we were more individualistic than our parents, and more atomized. Many of us returned with an almost celebratory sadistic streak, which was what worried the General, who remarked “I think we might be raising a generation that steps on baby birds.” So began a long, slow march into nihilism. Woodstock happened at the same time.

Let’s review the musicians at Woodstock 69 and Woodstock 99.

In 1969, there were Joan Baez, Ravi Shankar, Santana, Country Joe MacDonald, Sly and the Family Stone, Melanie, Jimi Hendrix, Joe Cocker, Sha Na Na, Ten Years After, Crosby Stills Nash & Young, The Band, Jefferson Airplane, Janis Joplin, The Who, Credence Clearwater Revival, Canned Heat, Grateful Dead, Johnny Winter, and some others that slip my mind at the moment. (Yes, I’m a generational chauvinist, because I think our music was better than most of the shit I hear now . . . Diana Ross, Bobby Hatfield, Stevie Wonder, Mavis Staples, and Linda Ronstadt didn’t need Auto-Tune . . . admitting I’m a big fan of Chris Stapleton now [fave: “Whiskey Sunrise”].)

Interestingly, Michael Lang, one of the original organizers for 69 was also named to head the planning for 99. Lang (mirroring our decontextualized antiwar naivete in 2002-3) thought he could reproduce the “spirit of 69” in 1999.

In 1999, the acts were Bush, Korn, The Offspring, DMX, Sheryl Crow, Jamiroquai, Megadeath, Godsmack, Chemical Brothers, Everclear, Insane Clown Posse, Oleander, Buckcherry, The Bruce Honrnsby Group, Los Lobos, Limp Biskit, Kid Rock, and a bunch of others. Certainly some more mellow voices (Crow, Hornsby, e.g.), but there were among the acts provocateurs who—caught up in their own egos and the power they wielded over an agitated crowd—egged on the audience as they increasingly merged into a throbbing mass of mimetic violence.

Give me somethin’ to break

Give me somethin’ to break

Just give me somethin’ to break

How 'bout your fuckin’ face?

I hope you know I pack a chainsaw (What?)

A chainsaw (What?)

A motherfuckin’ chainsaw (What?)

So come and get it

—Limp Biskit

There were drugs at both events (Santana famously played after the whole band had taken a hit of acid), but a lot more alcohol at 99. Joe Cocker was always on more shit than people could keep track of. Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin would both be dead from drug use the following year. But the “vibe” was markedly different. 1969 was an Age of Aquarius period, where youth rebelled not against their parents’ values so much as their hypocrisies. There was a strong identification with the nonviolence of the Civil Rights movement and a spirit of peaceful collectivism. The antiwar movement was in full swing. Joan Baez, at Woodstock 69, sang the labor classic, “Joe Hill.” Contrast that with the violent nihilism of Korn or Limp Biskit (and the hopeless atomized individualism that provided their context).

Woodstock 69 anticipated 50,000 people and got 450,000 +/-. Woodstock 99 had around 220,000. At 69, ticket fees were foregone in short order when newcomers overwhelmed the concert, which then went free. Food vendors that overcharged quickly went by the wayside (on hot dog stand was burned), and—though food was always in short supply—participants began organizing free food distribution. At 99, the participants had to go through security lines where they were relieved of their food and water, and vendors gouged them, at one point, selling bottles of water for twelve dollars.

But again—the vibe. Hippies versus frat boys would sum it up nicely (sexual assault was very common at 99, with no repercussions).

No 1969 peace or love anywhere in sight. Plenty of unity, though . . . to tear shit up. (Limp Biskit had ignited a frenzy earlier, with the song “Break Stuff,” which resulted in paramedics being overwhelmed, whereupon the talent-free, piece-of-shit lead singer Fred Durst walked away, and denied even a grain of responsibility.)

As the crowd grew more uncomfortable, more fucked up on alcohol and ecstasy, and more randomly violent, Red Hot Chili Peppers played the last set; and the organizers passed out 100,000 candles (for a vigil against school shootings). Not surprisingly, the crowd started setting fires. Red Hot Chili Peppers—whose bassist was playing the set buck-naked—decided that the responsible thing to do would be cover the Jimi Hendrix cut, “Fire.” Then an anticipated last act never happened, and the crowd set the stages, walls, tents, and trailers on fire, tore down the sound towers and the lights, attacked and looted the vendors, and besieged the organizers. Women participants were frequently and openly sexually assaulted. The fire department looked at it, and said to organizers basically, “You did this, you fix it,” wisely refusing to respond in the middle of 200,000 out-of-their-skulls mimetic lunatics. It was a Girardian nightmare.

1966—1999.

Vibe shift. (In 1970, President Richard Nixon—a crooked-ass Republican—established the Environmental Protection Agency. This March, Postmodern Caligula aka Donald Trump—another crooked-ass Republican—launched a 31-item process of deregulation by the same agency.) My favorite book in the Old Testament is Ecclesiastes, where Kohelet says, “What has been is what will be, and what has been done is what will be done, and there is nothing new under the sun.” I believe this to be true . . . in one sense . . . and I believe, paradoxically, that in history’s details, there is nothing not new under the sun. That’s why there would never be another Woodstock, nor will there by another Civil Rights movement, nor will any of the “return to the past” delusions of various reactionaries come to pass. It’s always all about the context.

Okay, as promised, let’s start now with the administration of Jimmy Carter’s presidency (January 20, 1977, to January 20, 1981).

Carter was the first President elected from the Deep South since 1844. His campaign in 1976 came at a point where Americans were caught between fatigue from a decade of convulsive politics (more than 300 urban riots [unfocused rebellions, whatever] since the King assassination), the mortifying end of the US occupation of Vietnam, and the scandals of the Nixon administration. Since the Republican Party had taken over as the [now dog-whistling] role of the party of white supremacy, and since black politics had drawn back within partisan politics without the focal point of legal Jim Crow, black voters were forced into a defensive posture within the Democratic Party, as the only remaining bulwark against revanchist white political power. But African Americans were still a minority within the party, which was also dealing with its own white “conservatisms.”

American black politics, such as it was, had decisively lost its independence.

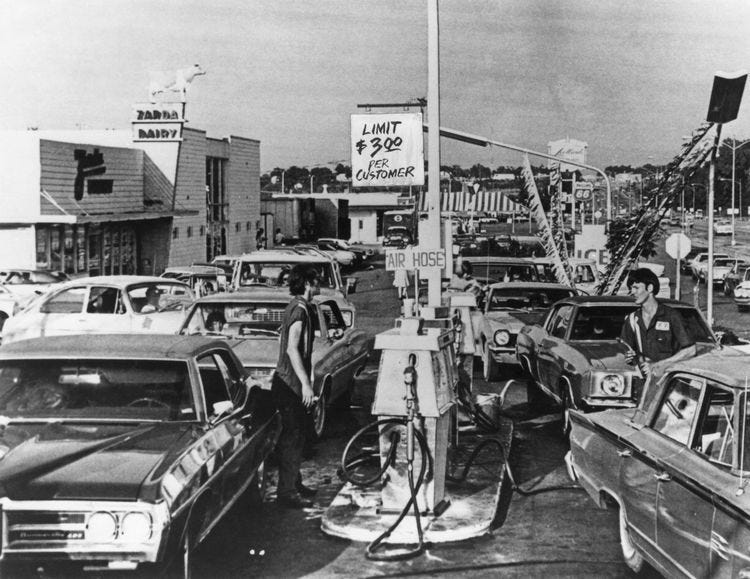

Meanwhile, Keynesian social democratic policies had become dependent upon the ever-strengthening military-industrial complex. More importantly, and for complex reasons, they were failing. When Carter took office in 1977, the US was already in the throes of an inflationary recession (stagflation) and an energy crunch.

On the foreign policy front, Carter found himself embroiled in an emergent new world order marked by the Sino-Soviet split, civil wars in Southern Africa, the Pacific, and Latin America, the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, the Iranian Revolution, and post-Vietnam turmoil in Southeast Asia.

The Carter presidency was as complicated as it was consequential; and its details have been overshadowed in our collective memory by his many admirable qualities (and amends) in later life.

He was a Cold War hawk who confronted the unions, and yet appropriated massive funds for public jobs initiatives, stepped up OSHA enforcement, raised the minimum wage, created the Departments of Energy and Education, supported the Strategic Arms Limitations Talks, sued for peace at Camp David, and granted amnesty to American draft resisters. He also sent aid to pro-Apartheid forces in Southern Africa to blunt leftists in Angola (in coordination with the Chinese!), and he armed Suharto’s government in Indonesia which massacred more than a quarter-million Timorese. He established and supported the anti-Sandinista forces in Nicaragua that Reagan would infamously grow out, at the same time returning the Panama Canal to Panama. He armed Iraq’s Saddam Hussein in its war with Iran. He also supported the Khmer Rouge (as did China), as a punishment on Vietnam (who’s combat-hardened troops had kicked China’s ass in a skirmish war a couple of years earlier). When the Soviets invaded Afghanistan (in support of the moderate Marxist government against more extreme Marxists!), Carter opened a back channel to Islamist forces in the Khyber Pass, the first step in the American build-up of a new force in the region: political Islam.

Carter’s National Security Advisor, Zbigniew Brzezinski, meeting with a young Osama bin Laden at Khyber Pass

Meanwhile, still reeling from its defeat in Vietnam, the victorious coalition of Marxists and Islamists who had overthrown the US-supported Pahlavi dynasty in Iran, swarmed the US Embassy in Tehran and took 52 American hostages. In 1980, just after Salvadoran Archbishop Oscar Romero was murdered by US-backed paramilitaries who’d slaughtered 600 people in one massacre, then raped and murdered four American missionaries, Carter sent a military task force to rescue the hostages in Iran, which failed spectacularly. Loss of confidence to Carter’s left and his right secured Ronald Reagan’s victory later that year, in much the same way Palestine and MAGA squeezed the juice out of Kamala Harris.

Looking back at Nixon, before we go forward, his abandonment of the Bretton Woods accords massively empowered the financial sector, call it “Wall Street” for short. Rent-seekers and speculators, as opposed to industrial capital that actually made things. During the period between the abandonment of Bretton Woods, through Carter and to Reagan, Wall Street’s power grew to heretofore unimaginable proportions (through currency speculation), and along with the growth came increasing political power . . . as a sector! While inflation and recession were beating the hell out of plain people, Wall Street grew into a political behemoth.

In the background, ever since Nixon, were what were called “Chicago School” economists, who were in fact most influenced by an Austro-British academic named Friedrich Hayek, became the business class’s ideological leading lights in a fightback against New Deal social democratic programs and institutions—whose functions they wanted to colonize for extraction (privatization). Privatization and deregulation were high on their agendas.

The supposedly laissez faire economists didn’t bat an eye when the government moved in to bail out big business. Between 1970 and 1980, the US government bailed out Penn Central Railroad, Lockheed, Franklin National Bank, and Chrysler.

The Bretton Woods system was dismantled in the early 1970s, thus deregulating international finance. We can credit this change to years of lobbying by bankers and conservative economists, led by the ubiquitous [Milton] Friedman. The IMF lost its regulatory function, while private bankers regained their influence. Speculation in currency trading exploded, producing windfalls for bankers.

The deregulation of international finance led to what has been termed the “financialization” of the U.S. domestic economy. As a result of financialization, investors could make quick profits by engaging in speculation (typically selling off dollars, while purchasing stronger currencies), rather than through long-term investments in manufacturing. And there was usually a government bailout waiting for the banks when speculative ventures ended badly.

The new, deregulated system had a negative impact on industry, eliminating many high-paying factory jobs which were offshored to low-wage countries. This process was facilitated by the free flow of capital across borders, made possible by deregulation. The New Deal system was thus replaced by a very conservative form of globalization, one that worked against the U.S. working class. (David N. Gibbs, author of The Revolt of the Rich)

Carter’s deregulation of the transportation industry was right in line with this. Bear in mind, Civil Rights veteran Andrew Young, Carter’s Ambassador to the United Nations, vetoed an arms embargo on Apartheid South Africa—a former King associate, former member of the Congressional Black Caucus, and soon-to-be Mayor of Atlanta. Strapped now to the Democratic Party, with Republicans a looming threat, the late modern black political class was being born, gestated paradoxically in the womb of Black Power (as identity politics).

As Reed, Johnson, and others have pointed out, the transition from Black Power to the black political class was a transition from black politics—the politics that engaged black people (often with white allies)—to black ethnic politics—an identitarian politics of “race relations” and Democratic Party “racial brokerage” (Reed). “Race” relations (a Booker T. Washington term), eclipsed all discussion of economic stratification, where “white” society’s class contradictions were mirrored in “black” society. The same thing is still in effect, with “racial equity” training for corporate HR departments, conducted by “race relations technicians” (Reed).

Out of this transition, Andrew Young’s Atlanta became what Adolph Reed called one of many forthcoming “black urban regimes.” (The popular television series, The Wire, was an examination of Baltimore’s black urban regime (with a white interloper), as seen through a gritty police procedural.) As this is written, the four biggest cities in the US are now led by black mayors, with 14 of the largest 50 cities having black mayors.

Thinking for a moment about a city government. First and foremost, it runs on money, to wit, tax money. We showed in earlier installments how deindustrialization and affluent “white flight” stripped away the tax bases of many cities at the same time it contributed to skyrocketing unemployment rates in cities that were now (due to “white flight”) majority or strong-plurality black (with black mayors . . . which defines the “black urban regime”).

A “black” led city has most of the same kinds of structural (capitalist) restraints as any other city, money to run the government being the chief concern among them. Most urban residents are poor or working class, which means (1) they make insufficient contributions to the tax base to keep the government afloat, and (2) they are vulnerable to civic projects (stadiums, e.g.) and gentrification from those who can afford to contribute more. This puts every mayor under pressure from corporate development interests to do the latter’s bidding. For a list of reasons we’ll table here for continuity, majority black cities were and are the most vulnerable. By the 1970s, the federal government was disbursing far less in assistance to cities, which increased urban dependence on “growth” models that relied on developers.

Meanwhile, black political leaders, like white ones, emerged from what is now called the “professional-managerial class,” and many were catechized for political life by corporately funded foundations. In short, they did not and do not identify with the poor and working class—black, white, or other—except discursively as elections approach. Even then, their language avoids issues of class, preferring the idiom of “racial” uplift. This was as true of former civil rights activists as it is now. “Thus, their class background, past political formation, and attendant ideological worldview predisposed them to a pro business agenda.”

Further solidifying black middle class support for the pro corporate model are the material benefits that accrue. The opening of high level positions in the public sector, and the awarding of public contracts to African Americans that had previously been limited to whites, has tended to benefit the black middle class. Thus, similar to urban regime theory as developed by Stone (1989), black urban regime theory identifies a dominant governing coalition, composed of a black led public sector and a white dominated corporate sector. This alliance represents the power structure in majority black cities. Its members cooperate to carry out urban economic regeneration projects.

The governing elite alliance is not without conflict. A major point of contention has been over affirmative action programs in the awarding of contracts. Nonetheless, there tends to be agreement on the overall pro corporate orientation of the regime.

The focus of urban regime theory is to analyze the process of cooperation and conflict between the public and private sector segments of the governing elite. To examine the content of this relationship the major, pro growth corporate organization is normally studied. For example, in his classic urban regime theory informed study Stone (1989) analyzed the Central Atlanta Progress (CAP), which was that southern city’s most powerful corporate planning organization. In contrast to this research agenda, a distinguishing feature of black urban regime theory informed studies is their focus on the impact of the pro corporate agenda on black working class communities and how regime elites legitimate inequality. For example, Oden (1999) found that Oakland’s black urban regime delivered only symbolic, rather than substantive, redistributive benefits to poor and black working class communities. Reed (1987) pointed to the discursive powers of black mayors – in this case, Atlanta’s Maynard Jackson – as key to obfuscating the material, class based distributive stakes embedded in the pro growth agenda.

These urban regimes have then become the basis—with their highly concentrated voting blocks in thrall to racial narratives—for the black political class more generally, one which is dependent upon the Democratic Party as its institutional ground, even as it wields considerable power within the Democratic Party (you could call it political co-dependence). This arrangement is the basis of the black political class’s “politics of racial brokerage.”

Returning now to American capitalism’s neoliberal turn—Nixon’s Bretton Woods abandonment, Carter’s deregulation/privatization, and Reagan’s financialization/debt regime (the true origin of what is now called “globalization”)—with the election of Bill Clinton as neoliberalism perfected itself, we saw the last nails driven into the coffins of both New Deal social democracy and the law (Glass-Steagall) protecting the savings and productive economies from speculation. It was with Clinton that Wall Street decisively supplanted any whiff of actual democratic process in the US, by becoming the power behind thrones via the “wealth primary.”

When the Party became the instrument of Wall Street, so did the black political class. And yet, because class contradiction within the fictional “black community” remained a brute material fact, “the mainstream Black political class found it easy to deflect and also to appropriate the moral position of the radicals or the revolutionary nationalists who acted as voices of a left populist standpoint in Black politics. And they did not even do it disingenuously . . .”

In one of my earlier lives, I worked in Atlanta City government in three different stints, actually, and I can recall my coworkers. Racial redistribution was not pointless. It made a difference with respect to things like zoning variances or getting in professional level civil service jobs and knowing people in the zoning board or in the planning bureau. As historian Will Jones [an old friend from the Carolina Socialist Forum, SG] points out, when people talk about the significance of public sector employment for the Black middle class, you tend to talk about teachers and quasi-professionals, but the most consequential difference comes with respect to postal workers, water bureau, maintenance and sanitation workers and clerks—I guess you’d say line employees who provide the material foundation and the security for a Black middle class—jobs that are unionized with civil service and trade union protection and pensions to make it possible for people to do things like buy houses and send their kid to college and stuff like that.

In that sense, transition cements popular support for the political class because it comes with those benefits. But the fact that we didn’t have any critique to make of how it was done in Atlanta, for instance, or the world’s fair in New Orleans or the giveaways to Prudential in Newark, or even the Coleman Young administration in Detroit. The scholarship tended to take the view that, not only were these new Black officials hands’ tied by not having control of the economic base of the cities, but it also presumed that this political class might have done something different if their hands had not been tied. (From an interview with Adolph Reed)

The men (almost all men, almost all white men) who operated behind the scenes to direct urban outcomes to their own advantage were mostly hedge fund managers, whose only interest in savings/production economies is how to harvest speculative returns from them (profiting even through failures [short sales, pump-and-dump. etc.]).

It was out of this milieu that Barack Obama emerged as a political player.

(Part 6 inbound)