The only change came from America as we increased our troop commitments in support of governments which were singularly corrupt, inept and without popular support. All the while the people read our leaflets and received regular promises of peace and democracy—and land reform. Now they languish under our bombs and consider us—not their fellow Vietnamese—the real enemy. They move sadly and apathetically as we herd them off the land of their fathers into concentration camps where minimal social needs are rarely met. They know they must move or be destroyed by our bombs. So they go—primarily women and children and the aged.

They watch as we poison their water, as we kill a million acres of their crops. They must weep as the bulldozers roar through their areas preparing to destroy the precious trees. They wander into the hospitals, with at least twenty casualties from American firepower for one “Vietcong”-inflicted injury. So far we may have killed a million of them—mostly children. They wander into the towns and see thousands of the children, homeless, without clothes, running in packs on the streets like animals. They see the children, degraded by our soldiers as they beg for food. They see the children selling their sisters to our soldiers, soliciting for their mothers.

—Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., from “Beyond Vietnam,” 1967

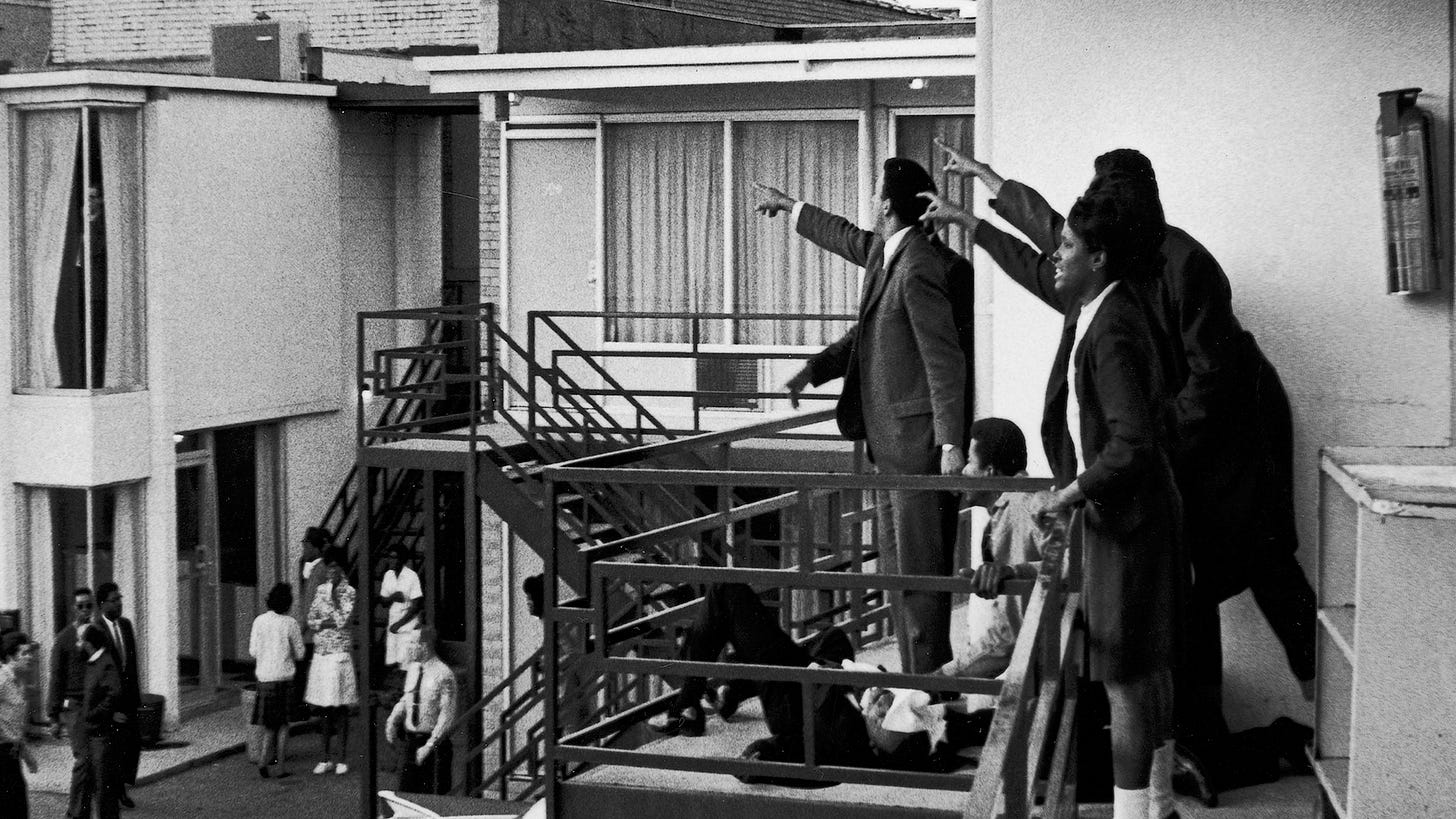

April 4, 1968. Memphis, Tennessee. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. is shot to death at the Lorraine Motel, where he was preparing to take part in a demonstration on behalf of striking sanitation workers.

Most pop-biographers of King go straight from the “I have a dream” speech in 1963 to the assassination in 1968, and King’s political development in between—as well as the public’s actual reaction to it—disappear from the popular consciousness.

After the legal breakthroughs of 1964-5, King—consistent with the strategic pivot recommended by A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin—turned toward the class politics laid out in the 1965 Freedom Budget for All Americans, a “universalist” social democratic document, with a list of concrete goals that would apply to all Americans regardless of ethnicity. He also adopted the criticisms of the Vietnam War voiced by the younger and more restless members of the SNCC.

When King delivered his “Beyond Vietnam” speech, exactly one year to the day before his assassination (April 4, 1967) at Riverside Church in New York City, he was met by the establishment—conservative and liberal alike—with approximately the same response one might expect today for denouncing Israel’s genocidal assault against the Palestinians. He was “canceled,” shunned, belittled, even by some of his own Civil Rights allies. A final cut in the whittling away of his influence—denounced for his emphasis on integration by a performative movement on his “left,” denounced as a communist by the right for the Freedom Budget, and now cut off from the establishment for calling out a war prosecuted by two Democratic and one Republican Presidents. Support for the war was diminishing, but in 1967, half of the country still believed the US should invade North Vietnam, forty percent didn’t even believe Americans had a right to protest it, and in 1968, sixty percent supported the police attack on demonstrators at the Democratic Convention.

From the time of the Montgomery Boycott in 1955-6, the FBI maintained constant surveillance on King until his death, with an order to find as much derogatory information as possible (the approval of wiretaps and surveillance continued through the Kennedy administration).

In the last installment, we left off rather abruptly with the germination of the Black Power “movement,” the Black Panther Party, and (then)Stokley Carmichael/(now) Kwame Ture. We reviewed the FBI’s counter-intelligence program (COINTELRO) and its actions against both the Civil Rights movement and Black Power organizations. We didn’t specify then, but various law enforcement officials murdered leaders like Fred Hampton and Mark Clark as well as jailing many others (some with cause, and some without). We also noted how and why Black Power organizations were more susceptible to adventurism and infiltration by the authorities . . . which broke these organizations, and left behind a residue of race-reductionism that was incorporated into the black political class, and from there into the Democratic Party (Bobby Seale ended up doing ads for Ben & Jerry’s Ice Cream).

All of which is to say, there is ample foundation for suspicion about the circumstances of King’s assassination (and Robert F. Kennedy’s soon thereafter); but that isn’t the subject of this series on strategy except to emphasize yet again the importance of a sober and realistic account of the strength and likely courses of action of one’s political antagonists. King, in fact, anticipated his own assassination, as evidenced by his eerily prescient “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech in Memphis the day before he was murdered, which ended . . .

I left Atlanta this morning, and as we got started on the plane, there were six of us. The pilot said over the public address system, “We are sorry for the delay, but we have Dr. Martin Luther King on the plane. And to be sure that all of the bags were checked, and to be sure that nothing would be wrong with on the plane, we had to check out everything carefully. And we've had the plane protected and guarded all night.”

And then I got into Memphis. And some began to say the threats, or talk about the threats that were out. What would happen to me from some of our sick white brothers?

Well, I don’t know what will happen now. We’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it really doesn’t matter with me now, because Ive been to the mountaintop.And I don’t mind.

Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land!

In that final speech, he reiterated his commitment to nonviolence as now integral to his Christian commitments. We’ll not delve into the various whodunit theories, but look into the aftermath, into what happened in response to his assassination.

In fact, what we do know, is that riots broke out in cities across the country.

In the wake of King’s assassination, Carmichael called for the respectful closing of black businesses, as opposed to riots, provoking Huey Newton—who encouraged and supported violence—to accuse Carmichael of being a CIA agent. J. Edgar Hoover instructed his COINTELPRO minions to connect Carmichael to the riots. Carmichael left the BPP, and this was the first of their splits. Carmichael married Miriam Makeba, a South African singer (whose music I still enjoy), and they moved to Guinea, where he changed his name to Kwame Ture in 1978.

His memoir is worth a read: Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture) (2005).

The same year as King’s assassination, a young history student named Barbara Fields received her BA from Harvard University.

Ten years later, under the tutelage of C. Vann Woodward, she earned her PhD from Yale, and went on to teach the history of the American South at Columbia University (after a time teaching at the University of Michigan, forty minutes away from where I now sit). With her sister, the sociologist Karen Fields, she would author a groundbreaking book titled Racecraft: The Soul of Inequality in American Life in 2012 (Verso).

Before we continue with “American black history,” I’m going to summarize Fields’ themes on “race” and “identity” as a prefatory midrash for understanding how the Civil Rights movement and “race” more generally were enclosed and weaponized on behalf of the ruling class, post-1968, and the movement neutralized into a more “acceptable” capitalist form.

Let’s step back and discuss race again.

We’ve often referred to three of our children as “biracial,” not because we believe in race as some biological reality, but because it’s popular epistemological shorthand. So, let me explain, using Fields’ (plural) perspective, the ways in which this term is problematic. At the end of the last installment, I historicized the term “race,” and here, near the beginning of this installment, we need to criticize the term’s current use. Actually, it’s been used that way for a long time, even across the ideological spectrum.

Race has been reduced in our minds to phenotypes, now that scientific study has debunked the social Darwinist fallacies underwriting nineteenth- and twentieth century “race science.” Our premise, then, is that there is no such thing as “race” in the strict scientific sense. Therefore, “biracial” people are in fact no such thing . . . in the scientific sense. So, what’s left? According to the Moynihan Report, trans-generational culture, the “black race’s” of which, in the US, is pathological because this category in the now cultural taxonomy, the members of which can nonetheless be identified phenotypically; but then again, when we deal with “biracial” and “multiracial” persons in actuality, we can all see how—within one generation—these “racial” phenotypes “blend out,” because in the scientific, not pop-genetic, hereditary realm, members of all so-called races are procreatively compatible. And Inuit can have babies with a Maori.

My sister did one of those DNA test some time back (something, I suspect many people do “hopefully,” desiring some racial result with motives accessible only to psychoanalysis). It turns out, according to this test (about which I have a lot of questions that aren’t urgent enough to pursue, given that I pretty much know who [not what] I am already), that we had some great (times N) grandparents who hailed from what’s now Gujurat India and others from a place in China near the Laotian border. I’m pretty sure no one would look at me now, and say, “That dude looks Gujurati or Chinese,” even though a couple of already “mixed” grandparents hooked up with a couple of other grandparents with ancestors from Asia during the eighteenth century.

In fact, in the racial taxonomy of today, I am “white” ( I admit I look winter-pale here, but hardly—except for the goatee—white . . . more of a light fawn).

The Fields sisters call race a form of “folk thought,” likening it to sixteenth century beliefs about witchcraft (ergo, the title “Racecraft”)—a widely held and axiomatic belief for which people can find plenty of “evidence.”

Looking back just ten generations, each of us has 1,024 biological grandparents. As the Fields sisters point out in the Introduction, as of 1970, in the US, twenty-four percent of “whites” had some African ancestry (as if “African” itself weren’t a gross generalization), and more than eighty percent of “blacks” had some non-African ancestors. Folk thought has its own vocabulary, which for some time has included “blood.” You or I have (name an ethnicity) blood. In fact, according to scientific studies, there are exactly eight types of blood, based on antigens and RH factors (I’m an A-negative); and while they’re not totally interchangeable with one another, each blood type exists among, and is completely interchangeable across, all ethnicities. I don’t have Finnish, German, Spanish, Italian, English, Puerto Rican, or Gujurati “blood” (though one might infer such a thing from my sister’s DNA test). This is “folk thought.” It’s popular, though. Many people will tell you that their temperaments or addictions or food preferences or libidos are because they have (name an ethnicity) “blood.” (See Barbara Duden and Silja Samerski on “pop-genes.”)

No one’s parents are monoracial, not because we are “mixed,” but because race is a modern myth, and therefore there are no bi-”racial” people. Still, we know what that means because we all speak the same “folk thought” idiom. It’s handy, it saves time, but at the same time, it can and does lead to accepting these linguistic shortcuts as somehow factual enough to employ as premises in an argument (the first step in the construction of ideologies).

The racecraft thesis is that race is “conjured” out of the practices of domination. These practices are race-making. When I went to Vietnam as part of an occupying military force, we were on one hand obliged to control the population and on the other hand fearful that many within that population (justifiably, it turns out) wanted to kill us. The reason we referred to them as “dinks” and “gooks,” from a psychological perspective, was we knew we would kill some of them. Killing is easier once you strip those you may kill (and will dominate) of their essential humanity. I became a racist (about Vietnamese) when I was there; and I’ve said since, on more than one occasion, “ground wars become race wars.” US soldiers of every ethnicity are now quite fajiliar with the term “hajji,” employed as an epithet. Not because of anyone’s “race,” but because—as Nikhil Pal Singh wrote—“warmaking is race-making.” Nonetheless, the war wasn’t about producing race or racism, but about geopolitical control, just as militarized police tactics, adopted from military counterinsurgency programs, are in impoversished, high-crime urban enclaves. Containment and control. Then comes the racism.

Barbara Fields said, “The purpose of slavery wasn’t to produce white supremacy, but to produce cotton, sugar, indigo, and tobacco.” Slavery was, first and foremost, a labor relation. This is why she and her sister said, racism isn’t caused by race (which has no ontological status, in the modern sense), but race is caused by racism . . . which is produced as a bi-product of some material relation (accumulation, war, etc.) prior to the employment of racism as justification after the fact. The mere perception of difference did not give rise to racism, but this notion becomes the metaphysical ground (the witchcraft) of something called “race relations.”

The first person to describe slavery as a “race relation” was . . . drum roll please . . . Booker T. Washington. Zine Magubane, remarking on the commercial anti-racism of Ibram Kendi, identifies Kendi with Booker T. Washington, based on their shared “racecraft” premise that treats the modern fiction of “race” as “a metaphysical force throughout history,” such that, beginning from this premise, “one can no longer penetrate history to understand its class character.”

This makes racecraft amenable to a capitalist ruling class. Corporations who contributed to Black Lives Matter’s “Equal Justice Initiative” included IBM, Microsoft, Comcast, and Target. BLM began as a mobilization (not a movement) after the murder of George Floyd by a (clearly racist) cop. More generally, the mobilization’s name—Black Lives Matter—aimed at the issue of police killing black people. Statistics, however, show that trigger-happy policing and egregious policies like “qualified immunity” apply across “racial boundaries. While it is true that black people are killed by cops at a higher rate than other groups (248 out of 1,173 in 2024), the greatest plurality of fatalities at the hands of police for decades have been classified “white.” In fact, the firmest correspondence between who is and who isn’t shot to death by cops is poverty. People (of any ethnicity) who live in high poverty areas are 3.5 times more likely to die at the hands of cops than people in low poverty areas. Which isn’t to draw some simplistic inference that cops are out to kill poor people. Each incident is, in one way or another unique. and poverty does correspond to high crime rates. Ideology is inadequate to capture the actual complexity, which hasn’t restrained ideologues right and left from trying.

Racecraft is like witchcraft not because it’s a cultural outlier, but because it is—in Karen Fields’ words—“pervasive, and therefore persuasive.” In the late fifteenth century, Western European belief in witchcraft was the norm, universal (just as racecraft is today), and evidence in support of that belief was abundant (crop failures, epidemics, and so forth), just as evidence in support of racecraft is today. When Black Power advocates adopted a racecraft perspective, it was because the division by '“race” was both apparent at the time and apparently intractable.

So. why am I going there in a series ostensibly devoted to using black history as a lens on political strategy? Pretty simple really. It’s arithmetic. 1,173 families have greater potential political force than 248. All we have to do is shift the focus from race to class, and make the goal reform of abusive police practices. This provides a series of concrete reforms for strategic focus; and it widens the pool of stakeholders and supporters who can be mobilized. Instead we went with Black Lives Matter, which has proven quite amenable to the ruling class, as have all identitarian politics. The pseudonymous Ghostofchrist01, writing on the Substack, Paroxysms, recently, pointed out:

McKinsey put the amount of money donated to racial justice causes in 2020 at more than 200 billion US dollars. The vast bulk of this money—over 90%—was pledged by financial organisations. Conducting another audit of the field in 2023, McKinsey’s researchers determined that the 1369 Fortune 1000 companies whose donations they had tracked committed a further 141 billion US dollars after the initial 2020 “racial reckoning,” between May 2021 and October 2022. Of the firms McKinsey looked at, fully 40% issued corporate “statements in support of racial justice” during the period surveyed and a further 30% made “external commitments to support racial equity” (through, for instance, donating to “affordable housing” charities with a racial justice focus). 25% of firms, meanwhile, made “internal commitments” to improving “diversity and inclusion” within their own organisations, by, for instance, “requiring diverse candidate pools,” seeking out “Black suppliers,” or by inviting outside speakers to address their employees on racial equity topics.

What is also significant is how this information was conveyed to readers. McKinsey deployed an emotive form of financial reporting that merged the functions of audit and activism, recalling BLM’s own commemoration-based rhetoric and the language of police abolition at the same time as it collapsed racial justice into the wider context of the pandemic itself:

«2020 has been a year of losses. First, lives have been lost—around the world, and in the United States in particular. Those lost lives are disproportionately Black lives. 2020 saw the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and countless others at the hands of police, and the deaths of more than 46,000 Black Americans from COVID-19. (Megan Armstrong, Eathyn Edwards, and Duwain Pinder, “Corporate commitments to racial justice: An update,” McKinsey Institute for Black Economic Mobility)»

At the height of the Summer 2020 protests, the Guardian’s Silicon Valley correspondent Kari Paul produced her own audit of how American tech companies were responding to the racial justice movement. In its previous tech reporting, the Guardian had often been critical of Silicon Valley’s record on identity issues, focusing, for instance, on the tech industry’s “toxic” culture for women. Although Paul’s article led (sceptically enough) with the question of “symbolism”—corporate leadership statements condemning racism—she had to admit that many firms were now putting considerable money and resources where their CEOs’ mouths were.

At Facebook, for instance, an “impassioned” statement from Mark Zuckerberg on 31 May 2020 claiming that “We stand with the Black community” was followed by a commitment of more than 200 million US dollars to support “Black businesses and organizations, in part through cash and … credit grants to Black-owned businesses and in part through” a new undertaking by Facebook to source its own internal “business supplies from Black-owned suppliers.” In addition, Facebook committed itself to “increasing the number of Black people in leadership positions by 30% in the next five years and doubling the number of Black and Latinx employees overall by 2023.” Facebook also announced plans to increase “hate speech enforcement on the platform, including prohibiting a wider range of hate speech in ads.” Despite these considerable financial undertakings, however, Paul noted that Facebook had faced widespread criticism from other large multinationals for the perceived insufficiency of its response to racial equity concerns. Mobilized by “civil rights groups,” over 1000 companies, “including Coca-Cola and Unilever,” suspended their Facebook advertising for the duration of July 2020 “in protest of the company’s failure to address hate speech.

I realize that this installment has been heavy on the critical side and lighter on history (at least in its granular particulars), but we are talking ultimately about political strategy, which requires a good deal more than factual accounts, in other words, a kind of pattern recognition that transcends the facts. Moreover, I have not placed what one might call proportional emphasis on clearly “racial” disparities that do stubbornly persist in culture, economics, law enforcement, and politics; but this has not been to deny them. It is to say that in doing political strategy, we are engaged—competently or not—in the “art of the possible,” a clearly instrumentalist endeavor; and that foregrounding race (and racecraft) is inimical to this project for all the reasons we’re outlining.

I don’t doubt that “black” communities and “white” communities (here I mean actually co-located people, not some aspatial abstraction like the “trekkie community”) will continue to be separate to one degree or another. What social democratic measures accomplish—with support from several communities, if they are colorblind—is greater distribution of wealth and social power to all on the lower economic rungs. If a “black” community has these additional resources, and the wherewithal then to pursue its own direction, the fact that some white people may not like them is increasingly irrelevant. Race hatred is an ugly thing, but without power (economic power is political power) it’s drained of its efficacy.

I’ll wind up this excursus with a few remarks on “intersectionality,” which is another PMC fave, descended from “identities,” or sociological taxonomies imposed on or adopted by individual persons . . . abstractions which supplant the irreducibility of actual persons. I once saw a Facebook post where an academic taxonomized herself as “I’m a white person with white privilege, and a woman without male privilege, but with cis-hetero privilege, who has a job that gives me middle-class privilege.” I actually new some thing about her based on more personal posts, but I tried to imagine how this demographic self-charting would play on a résumé or a dating app.

If police would simply kill a few more white people, a proportional representation of police killing if you will, and achieve parity (or in DEI-speak, equity and inclusion), would this mean the privilege disappeared, and, if so, is this the goal?

Intersectionality: (1) A feminist sociological methodology of studying the relationships among multiple dimensions and modalities of social relationships and subject formations. (2) The complex, cumulative way in which the effects of multiple forms of discrimination (such as racism, sexism, and classism) combine, overlap, or intersect especially in the experiences of marginalized individuals or groups. (3) How a person’s identities, such as their gender, ethnicity, and sexuality, affect their access to opportunities and privilege. (4) A critical concept that recognizes how individuals hold multiple identities, forming an intersectional identity that faces unique challenges at the intersections of those identities.

Okay, let’s look at “racism, sexism, and classism.” Racism, as we’ve seen, is is generated by specific modes of production, accumulation, and war, e.g., which then produces race (the social fiction), which then, with ideological assistance, reproduces racism. Sexism is unjust treatment of person based on her sex (a biological fact), and justified through rationalizations. Sexism is observable across ethnicities, and is sometimes difficult to parse because there are, in fact, differences between males and females underneath all the cultural clothing. Class, however, differs from both, in that it is determined (at least by Marxists who operationalized the modern concept) by the relationship (of an individual or a group) to the means of production (a material concept that can be confirmed through observation). Homogenizing these very different things as morally-reprehensible “isms” conceals not only their qualitative distinctions from one another, but the complex realities of race-making (which is far more than mere prejudice), male socioeconomic and political power (and other forms of power within intersex dynamics), and class-ism misrepresents class, a social relation which requires no such suffix. Identity transforms all three of these very different phenomena into mere moral failures even as it abstracts actual persons.

This move facilitates a kind of perpetual quasi-academic hair-splitting that can be traced from Stokely Carmichael’s “soft” denunciations of white allies who were actually supporting the movement, issued around the same time he said, “Seems to me that the institutions that function in this country are clearly racist, and that they’re built upon racism” (emphasis added). It’s a form of critique that devolves into a style; and any agenda, with no danger to itself, can adopt a new style. Absent any concrete political telos, and therefore without any basis for the development of a political strategy, the progressive taxonomization of “identities” serves only the academic quest to develop new theses for publication in arcane journals with a readership of one hundred, pseudo-intellectual one-up-manship among the chattering classes, and virtue-signaling to one’s ideological cohort.

What this tendency does not do—quite the opposite, in fact—is seek unity around shared interests across demographic taxonomies, and work in a disciplined manner toward accomplishing concrete political goals. (Little secret: working together overcomes cultural differences a lot more effectively than academic papers, HR diversity workshops, and liberal self-flagellation.)

Most people do not spend the majority of their time performing an identity; they eat, sleep, work, tend to children, get sick, deal with everyday emergencies, and so forth. These all deal with lack and precarity, in one form or another, and addressing those lacks and precarities. As Barbara Fields pointed out in an interview, if you ask people what they most desire, you’ll get an infinity of answers ranging from fame, to a girlfriend, to a vacation in the Bahamas, to a better babysitter. If you ask them what they most need, you’ll get more homogeneous answers: enough to eat, decent shelter, relief from debts, good schools, etc. If you ask them what they most dislike in their lives, there is a short list again of common answers: shitty jobs, or none, money shortages, lack of affordable health care, dick bosses, crappy houses, foreclosure, expensive transportation, etc. These are points of potential unity.

Returning now to history.

During the post-King-assassination riots, Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act into 1968 into law. The CRA specified “hate crimes” for the first time. It expanded the Bill of Rights to cover Native Americans living on reservations. It forbade housing discrimination (though it still ignored loan practices). It also included an anti-riot law (called by some the Huey Newton law).

In spite of the shortcomings of three key laws—the Voting Rights Act, the Civil Rights Act of 1965, and the Civil Rights Act of 1968—they set the stage for what has been, statistically-speaking, steady progress. In 1968, less than half of African American youth graduated high school. That number is now 90 percent. College completion nearly doubled. Household income (inflation-adjusted) rose by more than 40 percent. Black families living below the poverty line fell from 35 percent in 1968 to 20 percent today. Infant mortality fell from 35 percent to just over 11 percent.

On the other hand, home ownership has remained stagnant at 41 percent across those decades, and all those “racial” numbers remain skewed between black and white, which needs yet another explanation (provided below). Note, race-making plays a role, and always has in the US, but all caveats above apply.

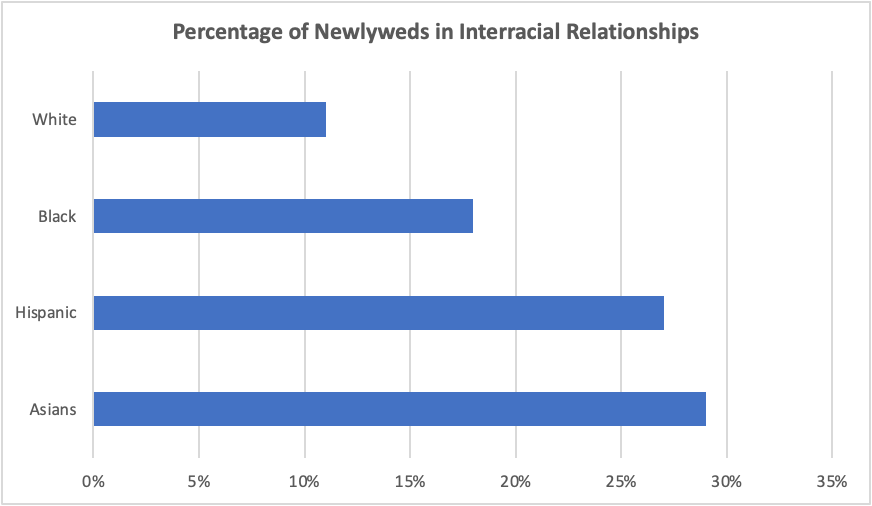

Since 1968, “interracial” marriage has increased by a factor of six. Federal law ended state “miscegenation” laws in 1967 (Loving v Virginia).

More to the point, approval of “mixed” marriages has skyrocketed.

I bring the latter up for two reasons: (1) it proves that integration changes attitudes, and (2) it further effaces distinctions by “race.”

After 1968, with the key laws in place, the movement dissolved and civil rights issues were pursued in the courts, putting these new laws to the test. The ramp that Randolph, Rustin, and King wanted to construct from race to class was dismantled, and the main beneficiaries of the post-68 reforms were well-to-do minorities. The number of metropolitan black mayors exploded. The Congressional Black Caucus was formed by Shirley Chisholm in 1969. Black professors became more numerous, as did black lawyers and doctors. The situation for poor and working class African Americans, however, especially in the cities, experienced little improvement, and often became worse. Equal access to higher education or housing presupposes prior access to the money to pay for them.

Meanwhile, during the seventies, new “rights” movements sprang up, something Justin Smith-Ruiu (iirc) called the “cultural nationalisms” of the era—other “minorities,” gay/lesbian rights (the other alphabeticals came later), women’s liberation, etc.

We have to understand that, in the short term after King’s assassination, King himself had been dropped like a hot potato by conservatives and liberals alike for his pivot to class politics and his opposition to militarism. War resistance continued, but the center of gravity for that resistance migrated to the campuses, even as black identity politics took hold in urban enclaves (and the campuses).

Black politics, such as it was, was taken up by the newly founded and rapidly growing Congressional Black Caucus, and the institutions underwriting the now “finished” Civil Rights movement atrophied. CORE adopted a black nationalist stance under Roy Innis, fell into disarray after attacks by COINTELPRO, and was reduced, by 1971, to being a kind of travel agent for delegations to African nations. The SNCC was bankrupt by 1967, and went through a fatal split in 1968, when Carmichael was replaced by Brown. By 1970, the SNCC had dissolved. The SCLC survived the assassination of King, but under the leadership of the much more conservative Ralph Abernathy, and shrank in its influence and efficacy.

This simultaneous loss of mass institutions and the migration of politics to the Black Caucus set the stage for the capture of “black” politics by the Democratic Party, because the CBC, which began with a social democratic agenda, had no real power within Congress, and no connection to (the now defunct) mass-politics institutions that might have mobilized the public on their behalf. Consequently, they became dependent upon the Democratic Party and its leadership. While this did foreclose the CBC’s independence, it opened the door to particular members to advance their careers as part of the DP apparatus . . . which in turn demanded fealty to the institution and its financial supporters.

Let’s gather up some context again.

New Deal social democracy differed from the Kennedy/Johnson administration’s War on Poverty initiatives in one key aspect. In the former case, e.g., the political narrative emphasized low wages and unemployment. In the latter case, the narrative weight was shifted onto “poverty.” The Moynihan Report is a case in point. “Poverty” was understood not as the second-order ramification of unemployment, lack of health care, or low wages, but as a first-order “social problem,” like a disease that needed curing. Moynihan’s infamous report suggested that “black” poverty was some kind of cultural deformation, with no reference to housing policies or unemployment. This epistemic shift was also a strategic one, a ruling class Trojan horse . . . “povertycraft,” if you like. The “poverty” episteme was another step away from New Deal social democracy (which itself had become overly dependent on what some call military Keynesianism).

Meanwhile, the non-racialized elements of American political economy were undergoing a step-change that would be consolidated in a few years as neoliberalism—a globalized capitalism led by financial speculators. With Nixon, under pressure from French gold purchases and the expense of the Vietnam occupation, the US withdrew from its Bretton Woods commitments in a stunning double-move—abandoning the gold standard and ending the dollar’s fixed currency exchange rates. President Jimmy Carter, in spite of his own feeble fidelity to social democratic programs, was in a weak position vis-a-vis both Republicans and conservatives in his own party, and he caved on the issue of deregulation of transportation industries. Worse still, Carter helped the mining industry break a strike in 1978. The Iranian hostage situation effectively ended his administration, and Ronald Reagan (who had cut a highly illegal deal with the Iranians before the election) beat Carter in the 1980 General Election. (Reagan cut more illegal deals with Iran after he was in office.) Reagan, in responding to the 1982 Latin American debt crisis, more or less accidentally set the stage for financial globalization. Long story short, neoliberalism transferred global power to Wall Street . . . an accomplishment that is past its expiration date, but still (though weakening in dangerously unpredictable ways) in effect. The point we’ve crept up on is that, with Bill Clinton and all presidents afterward, including and especially the Democratic Party, became political vassals of finance capital. (The megalomaniacal Trump may be a partial exception, but he’s a man so incapable of understanding complex systems that he’ll end up burning everyone’s house down, including his own.) Reagan also popularized the notion of “trickle-down economics,” the idea that enriching the top economic tiers of society would precipitate (pun intended) a “trickle-down” effect, wherein that wealth would then be shared into the lower tiers. “A rising tide raises all boats” idea. Except the economy isn’t rain or a tide . . . and this idea has been proven false again and again.

Returning now to the Congressional Black Caucus, which, in short order, became little more than a lobby for “black issues” within the Democratic Party, a political shelter into which African Americans had been driven after Nixon’s party became the new fortress of vestigial white supremacy. “Black” issues, meantime, were being combed out of any larger social democratic agenda. The CBC was eventually and fully drawn into racecraft, even as the politics of “identity” in other areas—embraced by powerful capitalists—squeezed social democracy off the public/political stage.

Martin Luther King Jr. would be resurrected as a political icon (and even cited by conservatives), cleansed of his social democratic and anti-militarist stains, enlisting the “I have a dream” speech in the service of a “post-racial” narrative.

This wasn’t a conspiracy, as anything can appear in retrospect, but the result of an impasse created when the strategically-sound, concrete race politics of ending Jim Crow was transformed into “progressive” racecraft.

“Social democracy” (concrete policies focusing on economics) was replaced by technocratic “progressivism” (a cultural cloak for “inclusive” capital). The language of class—exploitation, dependency, and ideology—was displaced by terms like privilege, allyship, intersectionality, positionality, and safe spaces, terms we can hear now in any HR briefing. Focus shifted from systems to individual moral capital, a welcome development on the part of actual capital.

It’s not accidental that DEI workshops, facilitated by the identity-industrial-complex, are contracted by corporate departments called “human resources.” Take a moment and think about . . . human . . . “resources,” and how readily we now accept being categorized alongside office supplies, water heaters, industrial feedstocks, and toilet cleaning products.

“The 7.5 billion dollar anti-bias, DEI training industry,” wrote Professor Catherine Liu of US Irvine, author of Virtue Hoarders . . .

. . .predicted to double in size in the next few years is a ripe area for maximizing return on investment. It is a growth area for speculation, but a spectacular failure in terms of actually producing the results it guarantees. It is an Andrew Tatesque hustle on a scale that make Tate look distinctively and pathetically small time. In Anthropology Now, Frank Dobbin and Alexandra Kalev published, Why Doesn't Diversity Training Work exploring the history and the measurable effects of corporate and higher education anti-bias training. When faced with “public relations crises, campus intolerance” or too slow diversification of the workforce, management resorts to “training.” Workers predictably resist attempts at employer control, even though or especially when the boss may present herself progressive. Jennifer Pan is writing a much anticipated book on this topic and I look forward to the empirical studies that she cites along with Dobbin and Kalev about diversity training. [The reason DEI is such an easy dog-whistle now for the neo-right —SG]

Leftist organizations like DSA have not found a better way of resolving conflicts within its membership. It is has had to hire of to outside consultant, PB Solutions to deal with complaints about harassment and bullying. Facing membership attrition and huge budget deficits, DSA has shown how difficult it is for contemporary organizations, not focused on worker priorities to articulate or implement an anti-corporate vision of organizational discipline and progress. Caucuses within DSA that prioritize class analysis have been forced out: Class Unity in Chicago is one example. People within DSA who invited Adolph Reed, Jr. to speak to NY DSA were tarred and feathered racists, with the The New York Times covering the cancellation of Reed’s Zoom talk in 2020. Liberals and some Leftists have internalized Human Resources, Democratic Party friendly approaches to identity management and every left organization after the Sanders campaign struggles with an atmosphere of distrust and mutual censorship. What the consultants produce for corporations and universities – manufactured trust of technical protocols is one of the ways that the division of labor in postindustrial capitalism pacifies dissent and destroys the very possibility of confrontation, contradiction and cooperation.

The black political class emerged within the Democratic Party. Writing in 2017, Professor Maurice Hobson of Georgia State University said:

In recent months, the world has watched as Atlanta—the black Mecca—threatens to elect its first white mayor (seen as a Trump-dog whistler) in decades. Americans marginalized by the vitriol spewed by the nation’s top office holder sit with bated breath to see Atlanta’s next move. One would be remiss in studying black electoral politics and voting behaviors since the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 without considering Atlanta. It has been more than 44 years since Maynard Holbrook Jackson Jr. became the first black mayor of a southern metropolis in general and Atlanta, Georgia in particular. In some regards, Jackson’s election as a big city mayor in the American South, a region wroth with the wickedness of white supremacy, was arguably the most resounding demonstration for black voting prowess until the election of President Barack Obama in 2008. Jackson’s election marked an era of black mayors in the doted “Black Mecca” that still exists, yet seems to be in jeopardy.

Historically, Atlanta’s notoriety as a black Mecca is based on three models: Black higher education—where six historically black institutions of higher education thrived; Black economic advancement—the emergence of a black merchant class that made the “Sweet Auburn” business thoroughfare the richest “Negro” street in the world and also created the West Hunter (now Dr. Martin Luther King Drive) business district; and Black electoral politics galvanized by the Atlanta Negro Voters League.

The accompanying narrative of this upper-class racial uplift orientation was one that matched, in almost every particular, the Reaganite embrace of “trickle-down” economics. The rising tide of the black bourgeoisie would lift all the other black boats.

“Development of Black Atlanta,” Hobson went on to say, “was partially due to tolerable relationships with the city’s white business elite. In this, Atlanta was deemed the “poster child” for progress in race relations because of the relationships between the city’s Black upper and middle classes and the white business elite.”

Hobson’s book, The Legend of the Black Mecca—Politics and Class in the Making of Modern Atlanta, details all the ways that Atlanta’s black bourgeoisie trampled poor and working class African Americans to get to and stay at the top. While setting themselves up as spokespersons for “the race,” they tried to break strikes and supported developers as they gentrified and wiped out old neighborhoods.

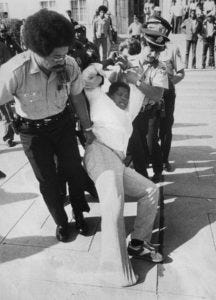

“Sanitation workers on strike; at Atlanta City Hall a protester is dragged away, Atlanta, Georgia, April 12, 1977.” One of the cops sports an afro. Photo by Billy Downs.

A . . . flashpoint for intraracial class conflict treated in The Legend of the Black Mecca was the drive to land the 1996 Centennial Olympiad in Atlanta. Mayors Andrew Young and Maynard Jackson worked closely with members of the city’s largely-White business elite, led by attorney and investment banker Billy Payne, to make a formal bid for the Games. As a result of this interracial collaboration, “the chief executive officers of BellSouth, the Coca-Cola Company, Delta Airlines, and Georgia Power” were all among the notable power players who lent their resources and connections to help garner a successful bid. (Winston A Grady-Willis)

Next installment: intraracial class stratification, respectability politics, the Obama phenomenon.

Manhattan, 2015, protest against police brutality and income inequality

You do not get DNA from all your ancestors. As close as about 5 generations back, depending on all the various generic stuff, you probably have at least one genealogical ( who slept with who ) ancestor who is not also a biological ( you share DNA ) ancestor - you literally have no physical relationship to them. Go further back, usually, and you encounter pedigree collapse ( your great aunt on one line is also your great grandmother on another, or whatever ).

Fantastic work! And yet… and yet. What do you have to say about blacks, though? There’s still something special going on here with blacks in the United States. What is it? It cannot be washed away in colorblind “Social Democratic politics,” and I am a communist and I am ultimately a “class reductionist”!