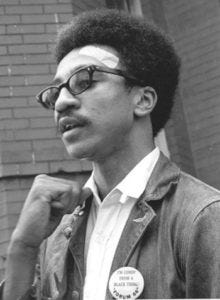

June 16, 1966, isn’t on the commemorative calendar in black American politics, but it probably should be. On that date, Willie Ricks, a Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) field secretary, and Stokely Carmichael, SNCC’s new national chair, electrified the crowd in Greenwood, Mississippi, on the March Against Fear from Memphis to Jackson, Mississippi, when they began chanting “Black Power! Black Power!” The chant—and Carmichael’s speech before the gathering—sent shock waves through the news cycle. I remember that galvanizing moment very clearly; I was then a 19-year-old college student and felt a powerful rush from two snippets of the chant I heard in the press coverage of the moment when Black Power was born, as both a slogan and a movement. It seemed to offer, or augur, an exciting new brand of radicalism, and revolutionary confrontation, in the movement’s next phase.

—Adolph Reed

Louverture, Dessalines, Cristophe, Pétion. Dubois, Washington, Garvey. MLK, Baker, Carmichael/Ture, Newton. There was never a real and cohesive African America, and therefore there could never be a singular Black Political Leader. This is why, speaking from the intelligence side of any strategic analysis, categories like The Black Vote, or any other way of speaking about black Americans with a definite article, is deceptive in a way that deceives the speaker him- or herself.

Even the category “black Americans” begins to crack and peel when we try to decide whether this wording stands for a genotype, a phenotype, a “blood quantum,” a culture, a mark, whatever . . . a person, who has one parent who is “white” and “Asian” and another parent who is biracial white-and-black, may look “black” enough to be marked by the surrounding subculture (is he or she in Jackson, Mississippi or Harlem or Phoenix or on a farm in Western Massachusetts?) as “black” or “high yellow” or someone who is multiply hyphenated. There’s a powerful psychological component to questions of “authenticity,” too. Personally, having done a fair bit of political organizing in the South, I was struck by how many of the most absolutist nationalists I met were very light-skinned. Colorism reversed.

Strategically speaking, the definite-article error (from The Negro of the DuBoisian era to The Black Vote of today), being self-deceptive, misleads political tacticians to false presumptions (as it recently did when Trump won the largest share of black voters of any Republican in the last six decades). It’s an error, however, that gets people paid, because both white racists and white liberals who make this error actualize various black leaders’ power by treating some one person (or any person) as somehow representative of this fiction. We’ll talk more about this as we approach a conclusion.

Returning to our historical narrative . . . circa 1965, after the passage of the Voting Rights Act.

Enter COINTELPRO, or the FBI’s Counterintelligence Program, established in 1956, at the peak of McCarthyism, to rout out domestic communists and all those thought to be their sympathizers. Headed by the ever-paranoid and vengeful J.Edgar Hoover. Hoover’s hatred of King was legendary, as was his hatred of the Kennedy political dynasty. Readers can research elsewhere—it’s not very hard—to see the kinds of tactics, legal and extralegal—that COINTELPRO employed. Surveillance, dirty tricks, harassment, and infiltration.

I know I’ve skipped over a great deal, but we need to look now at the link between police surveillance and infiltration and the rise of performative politics wearing the mask of “radicalism.”

(Yeah, I have a thing about guns . . . not a good one.)

Bear in mind, as we continue, the distinctions between mobilizing and organizing, between provocation and persuasion, and between the symbolic and material. All six can and sometimes ought to be incorporated into a political strategy, but to win—to actually achieve some strategic goal—these aspects need to be a concert. It’s too easy, absent an informed appreciation of strategy (and its subsets in campaigns, tactics, and techniques), to believe that one can achieve the same result by only playing the strings or the wind instruments, the keys or the percussion.

While black organizers in the South, pursuing nonviolence as a strategy, pressed forward to the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act, urban black enclaves in the North and West, influenced by Malcolm X and others who rejected nonviolence, were embracing a kind of hyper-masculine black identity politics that later came to be named the Black Power movement. It manifested as urban rebellions/riots, in Harlem in 1964, Watts in 1965, and Newark and Detroit in 1966. The assassination of Malcolm X (at the hands of the Nation of Islam, but widely blamed on the government . . . the whole truth is still not known) only added fuel to the fires.

Called a movement, it had neither a unitary ideology nor coordinated strategic goals and methods. Some identified with international struggles against colonialism, others with “buy black” entrepreneurial emphasis, other with Marxism-Leninism, and some with a contradictory mix of approaches. In reality, the efficacy of the many splinters of this ostensible movement was limited to very local efforts. The Black Power movement was less a movement than a vibe, a movement with no reasonably coherent strategic orientation, but long on transgressive symbols, from hairstyles to adopting new names (Stokely Carmichael became Kwame Ture.) Let’s back up a bit.

On August 6, 1965, President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act. Five days later, after years of housing discrimination and police abuse in the black neighborhoods of Los Angeles, an incident involving the police beating of a drunk driver developed into a rumor that cops had killed a pregnant black woman in the Watts neighborhood. The rumor ignited a tinderbox of seething resentment. The ensuing rebellion, or riot, or uprising—it was called all three—escalated rapidly, and within a day the National Guard was called into to quell the uprising, after Chief of Police William Parker compared black people to “the Viet Cong.”

In the wake of Watts, the SNCC split from the Civil Rights coalition and abandoned the very principle of nonviolence that was in their name, allying themselves with the white radicals of the Students for Democratic Society who were increasingly focused on actions against the US occupation of South Vietnam. The SDS, while more organized than early Black Power advocates, was largely restricted to college campuses, where they did more to create new academic sub-specialties as the emergent New Left than they did in actually affecting politics (the war would end ten years later in an ignominious defeat at the hands of the Vietnamese). The SDS would eventually splinter into the Weather Underground Organization (the Weathermen), a violent outfit of young self-styled “revolutionaries.”

To understand the Black Power “movement” and its loose association with other groups of adventurists, one has to appreciate the zeitgeist. The Civil Rights movement had awakened much of the baby-boom generation, restless in the face of the manifold hypocrisies of the comfort-consumerism of their war-weary elders. Black liberation had also awakened the very real (and legitimate) grievances of women, Chicanos, indigenous Americans, and others; and the draft-era Vietnam War provoked young people (and, eventually, disaffected veterans) into opposition to the war. This was when the term “generation gap” entered the popular lexicon. To those in power, it seemed the world was falling apart, and on the other hand, many young people saw it as the dawn of some new age. These ideas were not forming, however, within any politically teleological or strategic mindset but as what is called today a vibe. Radicalism became cool, but it was also associated with transgression for its own sake, mindless hedonism, the magical thinking of performative politics . . . and drugs. Many of my generation became “rebels without a cause.” Gestating within this foment were two political cancers: adventurism and identitarianism.

The Black Power movement flirted with both (as did the Weathermen and others).

By “adventurism,” I mean the privileging and advocacy of violent or militaristic ideas and actions, generally without any reasonable assessment of the consequences. In fact, the adventurism of the mid- to late-sixties was characterized by magical thinking, to wit, the fantasy that the aroused masses would arise in the wake of adventurist actions and flock to this or that group’s banner. What it aroused instead was public fear that tacitly endorsed the extralegal practices of a likewise aroused and fearful government.

That’s how COINTELPRO got involved. Not just because black dudes with berets and guns posed in front of California’s capitol building, triggering J. Edgar Hoover’s (and later, Nixon’s) paranoia, but because adventurists are easier to infiltrate than more staid and systematic political planners. Caricature is easier than character. Which is not to say that some “Black Power” leaders were without character or insubstantial, but that when performance takes priority over more sober and well-informed strategy, overreach is the danger, with a cascade of unintended consequences. Carmichael/Ture, for example, and in spite of his famously sexist gaffe, had a PhD in Philosophy, and he was influenced—as were many—by the works of Franz Fanon. Their error, apart from not having a crystal ball, was mistaking the stochastic ferment of the time for an incipient revolution.

That ferment was pronounced in black urban enclaves.

We need to back up again, just a bit, to enfold the narrative in a thicker context.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, I was born five years into the post-World War II baby boom, which lasted from 1946 until 1964. Between 1947 and 1951, William Levitt & Sons built a mass-produced community of three “neighborhoods” of mass produced and modular houses in Long Island, New York, and it was named Levittown. By most reckoning, this was the first tract-house car-suburb. Levitt had learned mass production using interchangeable parts while he served in the Navy during the war, and applied standardization to mass house construction. Levittown was designed to cash in on a postwar economic boom that was buttressed by housing loans made available to all veterans as part of the GI Bill. Levittown did not allow black residents, even though the law required it to. Developers and real estate agents skirted the spirit of the law through loan policies (redlining) and other disincentives to accomplish de facto housing segregation.

These housing policies had been around since the fifties, but they’d reached crisis proportions by the time first Malcolm X and then Black Power advocates came on the scene. This made inner cities a prime recruiting ground for the (positive) black pride tendency and the (less positive) bend toward adventurism. (Preston Smith II’s book, Racial Democracy and the Black Metropolis: Housing Policy in Postwar Chicago, is an excellent account of these policies. See also his interview here.)

An array of phenomena materialized from housing policies and “white flight,” that is, the migration of white urban residents to commuter suburbs. Housing policies favored suburban development (and facilitated “white flight”) and left urban areas with a diminished tax base, progressively crumbling infrastructures, and substantial job loss. This was a different kind of segregation than the “other side of the tracks” segregation of the Jim Crow South: the urban ghetto.

Housing discrimination and ethnic-enclave settlement patterns limited most blacks to the same proximal urban neighborhoods, even though those black ghettos were internally stratified along class lines, with the black middle class occupying better, safer housing stock. Postwar urban renewal further concretized this residential apartheid, as federal interstate highways and other massive public projects bisected black neighborhoods, dispersing residents, destroying the urban fabric, devaluing adjacent property, and often serving as physical walls dividing black areas from those of other ethnicities. Slum clearance and the construction of tower-block housing, which were widely supported by downtown commercial interests and social reformers, momentarily improved the environs of those previously relegated to dangerous, unsanitary tenement conditions, but these developments were in effect a form of vertical ghettoization. (Cedric Johnson, “The Panthers Can’t Save Us”)

Whereas the Jim Crow form of segregation integrated black people into the larger economy as a sub-proletarian class of service workers, the latter form isolated urban African Americans altogether. Joblessness combined with financial inescapability to form a shadow economy that was in many respects outside of the law—what Marxians might call a lumpen-subeconomy. Crime in urban ghettos corresponded to joblessness and hopelessness, and in fairly short the hustler economy was reflected intergenerationally as a hustler culture. And yet, even subcultures remain permeable to the larger political economy and are in one manner or another integrated with those larger economies.

I would advise those who think that self-help is the answer to familiarize themselves with the long history of such efforts in the Negro community. and to consider why so many foundered on the shoals of ghetto life. It goes without saying that any effort to combat demoralization and apathy is desirable, but we must understand that demoralization in the Negro community is largely a common-sense response to an objective reality. Negro youths have no need of statistics to perceive, fairly accurately, what their odds are in American society. Indeed, from the point of view of motivation, some of the healthiest Negro youngsters I know are juvenile delinquents: vigorously pursuing the American Dream of material acquisition and status, yet finding the conventional means of attaining it blocked off, they do not yield to defeatism but resort to illegal (and often ingenious) methods. They are not alien to American culture. They are, in Gunnar Myrdal’s phrase, “exaggerated Americans.” To want a Cadillac is not un-American; to push a cart in the garment center is. (Bayard Rustin, 1965)

The subcultures of the ghettos were, no matter how different or even transgressive, incorporated into the logics of capitalism—competitive, transactional, preyed upon and predatory, and always underpinned by what Marxists call primitive accumulation (plunder). In a typical capitalist core-periphery dynamic, value was extracted (and still is) from this periphery (selling clothing, food, entertainment, weapons, and other consumer goods, produced from “the outside”) and the eco-social pathologies of accumulation dumped back into them.

When Chief of Police William Parker (above) compared black people to “the Viet Cong,” the comparison came easily. These urban peripheral subecononomies were to be separated, contained, and in some cases almost militarily occupied. I reviewed Nikhil Pal Sing’s Race and America’s Long War, an excellent book on this “occupation,” here.

It was into this urban milieu in the larger cities—North, South, East, and West—a racialized class phenomenon, that the younger organizers, often themselves class conscious, of the post-1968 SNCC projected themselves. As part of a “new left,” taking Carmichael/Ture as an example, the class critique (now itself racialized in response to the race-making of capitalism itself) was turned onto the “elder” leaders of the Civil Rights movement, who were now denounced from within as petite bourgeois. This was true, in many cases, but remember that Carmicheal/Ture himself was a PhD (he grew up, however, as a West Indian immigrant, in working class New York). As Chairman of the SNCC (1966-67), and in the face of still relentless violence against the movement, he refocused the organization’s narrative on “black self-reliance,” or “black power,” a term into which whites projected their fears and many African Americans projected something more vague and visceral than Carmicheal/Ture’s rhetorical conception.

At the same time, opposition to the US occupation of Vietnam was ramping up, a development welcomed by the Fanonian Carmichael/Ture, who understood the Black Freedom Struggle in internationalist terms. He was, in fact, the person who first encouraged King to voice opposition to the war, something many Civil Rights leaders resisted lest it “dilute” their focus and galvanize public opinion against them.

Carmicheal/Ture stepped down as SNCC Chair to tour the US with his Black Power message, voicing support for the urban revolts, and was replaced as head of the SNCC by adventurist firebrand H. Rap Brown, who began proselytizing for open and armed rebellion.

These developments were met by COINTELPRO, which became, in effect, a task force aimed at breaking the Black Power “movement.” It didn’t help that Brown himself, paradoxically mirroring the racist LA Chief of Police William Parker, encouraged his followers to become America’s “Viet Cong.” Carmichael/Ture’s positions remained far more nuanced, but this was just one (quite telling) example of the aforementioned projection of adventurism into the diffuse (and eventually fragmented) idea of Black Power.

If I seem to be bearing down on these developments in greater detail—and more critically—than others, it’s because (1) I was a witness to them, at least generationally, and (2) as a former revolutionary Marxist, I was obliged to study (and justify) them as part of our historical canon.

Participants in these events believed there was a revolution on order. Cubans had successfully overthrown the corrupt Batista regime just a decade earlier, and that had become—in spite of tremendous differences in context—talismanic for the “revolutionary left” and several Black Power formations, the most memorable of which was the Black Panther Party. Likewise, key figures in the government believed revolution was on their doorstep, too. Consequently, the actions on both sides became more warlike . . . but it was, from the beginning, a very unequal war.

The Black Panther Party wasn’t the only formation, but the largest and most visible, so it’s through the struggle between the BPP and the government that we’ll retrospectively try to discern some strategic lessons.

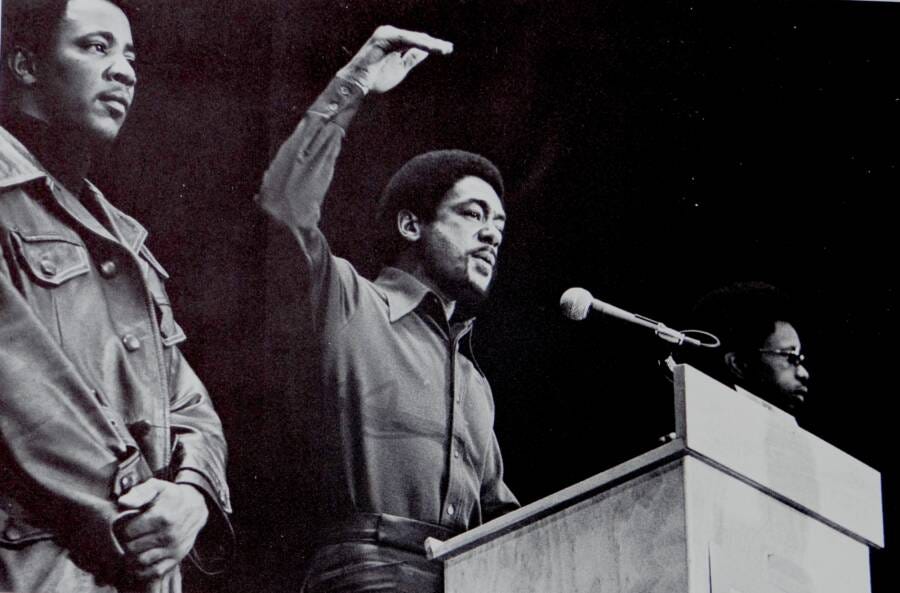

In 1966, Oakland, California activists Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale, organized the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense.

Huey P. Newton

Bobby Seale

Growing out of a Maoist-inflected formation from the East, called the Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM), the BPP found fertile ground in the urban ghettos created by housing policy/white flight. Northern and Western cities had been left largely unaffected by the increasingly effective struggle against legal Apartheid in the South.

RAM and then the BPP rejected the nonviolent strategy of their predecessors, ideologically incorporated a more explicit class analysis (citing the Black Communists of the past) and an anti-imperial stance (inspired by Franz Fanon), and took inspiration from Malcolm X. They also built in (wisely, in my view, at least at the local level) community organizing principles taken from Saul Alinsky’s Industrial Areas Foundation.

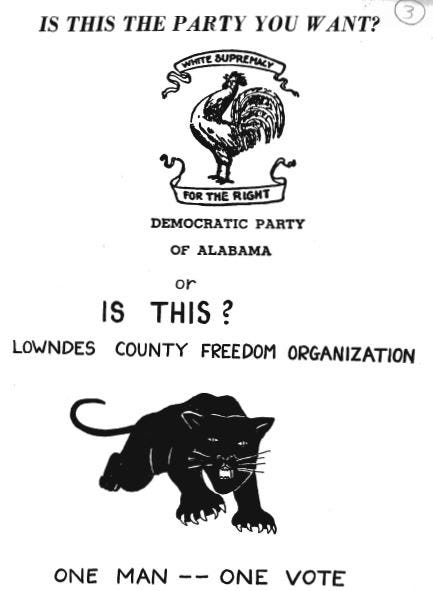

Carmichael/Ture was already in touch with Newton and Seale in 1966, and even keynoted a Black Power conference at Berkeley. Carmichael/Ture had been organizing the Lowndes County Freedom Party in Lowndes County, Alabama, a formation that not only advocated armed self-defense, but which had adopted a black panther ballot symbol.

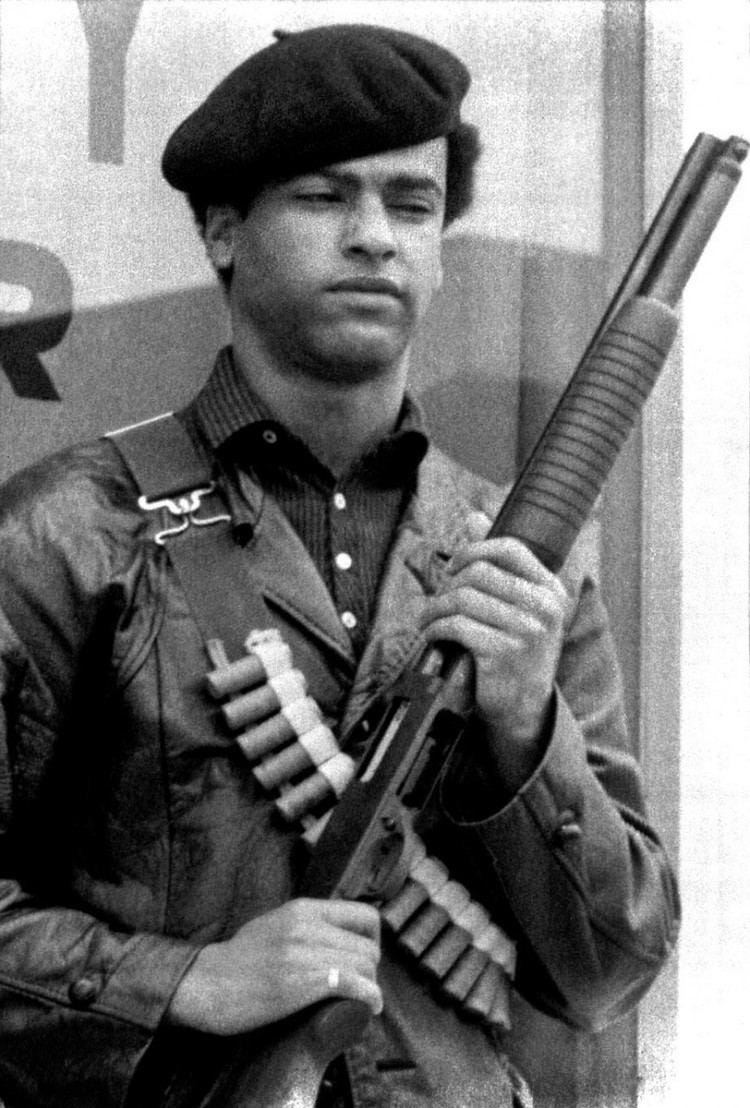

It was this symbol which gave rise to the BPP’s name, along with which Newton promoted a provocative cosplay uniform: Black pants, black leather jacket, and black “Che” beret.

Newton and Seale took up a study of California’s gun laws, and, invoking the Second Amendment in much the same way the neo-right does today, whereupon BPP members began openly armed patrols of Oakland to “police the police,” the latter of whom had a well-deserved reputation for brutality in black neighborhoods.

Again, a short excursus is necessary to keep the focus on strategy and strategic context. Boys and men, as we all know, can develop an unhealthy relationship with firearms. Which is not to say that (even though this writer has adopted nonviolence an article of faith) firearms are not effective (sometimes) for self defense, or that men can’t own and use firearms without forming psychosexual attachments to them. But the truth is—and I speak from long experience with firearms of all kinds and in many circumstances—guns are extremely dangerous instruments that should only be handled by people who are well-familiarized with safety precautions and proper use, and who themselves have been formed in the habits of prudence, good judgement, and humility. To wield a firearm is to wield tremendous power, as well as the potential for tragically irreversible accidents. Firearms make angry people more dangerous, foolish people far more foolish, inept people into time bombs, and they amplify immaturity in the already immature. They also actualize the potential for some people to become bullies and thugs. One or more of the aforementioned applies to a large plurality of men, in my view. I cite men in particular, not because women don’t use firearms, or because some women can also become gun fetishists, but because these tendencies—based on popular constructions of masculinity—manifest far more frequently among men than women.

^^^Some gender exceptions, but my remarks on fools and psychosexual attachment remain.

In 1967, when armed BPP members, in a highly publicized event, escorted Malcolm X’s widow, Betty Sabazz, to the San Francisco Airport, recruitment into the BPP bumped up. In May that same year, Newton and Seale led an armed contingent of twenty-three BPP members onto the steps of California’s capitol building in Sacramento. Shortly afterward, Republican Governor Ronald Reagan signed a bill repealing California’s open-carry law. (Since 1964, a growing fraction of the Republican Party [including Reagan] had been dog-whistling to disaffected white supremacist Democrats, adopting “States rights” language, which culminated with Nixon’s successful “Southern Strategy in the 1968 elections. The South has been solidly Republican ever since.)

The BPP developed a ten-point program that read:

We want freedom. We want power to determine the destiny of our Black Community.

We want full employment for our people.

We want an end to the robbery by the Capitalists of our Black Community.

We want decent housing, fit for shelter of human beings.

We want education for our people that exposes the true nature of this decadent American society. We want education that teaches us our true history and our role in present-day society.

We want all Black men to be exempt from military service.

We want an immediate end to POLICE BRUTALITY and MURDER of Black people.

We want freedom for all Black men held in federal, state, county and city prisons and jails.

We want all Black people when brought to trial to be tried in court by a jury of their peer group or people from their Black Communities, as defined by the Constitution of the United States.

We want land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice and peace.

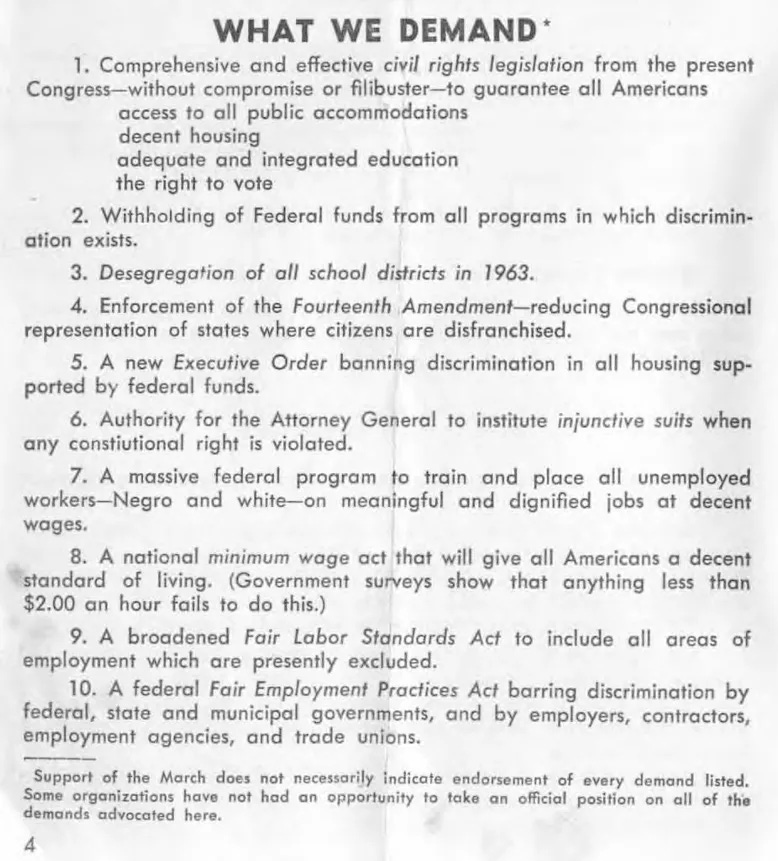

As a veteran of leftist pseudo-parties, I recognize this form of deracinated “program,” a list of “wants” or “demands” behind which there is zero capacity to make the government meet them—a formalized list of grievances presented as politically impossible end-states. But again, given the ferment of the time, it was easy to fall for the “flock to your banner” fantasy of a cataclysmically engendered utopia. It was equally easy for the government to see the state of diffuse disturbance as an existential threat. No one, after all, could see into the future the way we can now see back into the past. But contrast the BPP program ^^^ with the demands from the March on Washington.

Specific, targeted actions without abstractions. Anyway . . .

It’s totally true that the government, specifically COINTELPRO, but also law enforcement generally, acted reprehensibly, violating people’s constitutional rights, assassinating leaders, making bogus arrests, infiltrating the BPP and others with undercover agents, and spreading divisive rumors and lies within their ranks.

From a strategic viewpoint, however, it must be said, these actions were entirely predictable. Both sides had pretty openly declared themselves to be at war with one another, and in war, the rules are always suspended. Unlike their ostensible spiritual guide, Mao Zedong, the BPP failed to understand the strategic principles required by a weaker force in the face of a stronger one (political intelligence, tactical retreat, selective engagement, quietly building power, favoring movement over position, etc.). Instead, they adopted a kind of macho belligerence, admittedly alongside some local (Alinsky-style) initiatives, like the Breakfast Feeding Program for school kids (which J. Edgar Hoover insightfully called their most dangerous activity).

The BPP failed in political intelligence even as it excelled in stylistic provocation.

In October 1967, Newton engaged in a gunfight with Oakland Police, killing Patrolman John Frey. Wounded himself, Newton was arrested, and a “Free Huey” campaign spread through the ranks of Black Power advocates as well as other leftist grouplets.

The BPP began recruiting from street gangs, whereupon in 1968, BPP member Bobby James Hutton was killed in a shootout with Oakland Police, further escalating the situation. Support came in from college campuses and celebrities, as the revolutionary vibe became popular (and ever more performative), but the biggest influx of actual members were “off the street,” and with this influx the Party was infiltrated by a kind of lumpen-ethic married to a politics of paranoia.

While BPP support was trendy in certain circles, it was—for most of America, including substantial numbers of African Americans—irresponsible, frightening, or both. Provoking the authorities as the Civil Rights struggle had, employing nonviolence as a strategic principle, had been politically effective at mobilizing broad public support. The BPP’s provocations had the opposite effect, even as it became a kind of proto-woke litmus test for the self-styled radicals of left grouplets, academics, and “edgy” celebrities to voice support. (This was one of the early instantiations of the fusion between identitarian politics and a culture of infinitely subdivisive denunciation and [white liberal] self-flagellation, which the capitalist class incorporated as another method of both accumulation and strategic co-optation.)

It’s been noted more than once that by 1975, between uncritical recruitment, COINTELPRO and law enforcement interference, and an increasingly paranoid style of “war” politics, the BPP was half thugs and half cops. This is what happens in the absence of concrete strategies: performative actions that aim nowhere and vulnerability to institutional infiltration by undercover actors (in the practical and theatrical senses) who gain entry by imitating these performances. (An old movement rule from my past—whoever is calling for an escalation to violence is probably a cop.)

While the break of Black Power from the Civil Rights Movement was portrayed by Black Power advocates as “the next step” in black politics, and yet Black Power was—in many respects—a regression.

With the passage of the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act, the movement that had accomplished them had a broad discussion and debate about “where next?” Bayard Rustin, in particular, along with King and Randolph, argued that the movement should move “beyond race relations to economic relations” (Rustin), which contradicts the narrative that was coming out of Carmichael/Ture’s SNCC that it was Rustin’s was essentially a bourgeois movement. Rustin argued aggressively for further social democratic reforms—outlined at the March on Washington—that would be universal, in the sense that they’d apply to poor and working class of all ethnicities.

Rustin may not have had a crystal ball, but he accurately predicted that the Black Power emphasis would lead not to greater political power, but self-restriction within a race-reductionist framework, government crackdowns with public support, and eventually to a refurbished black sub-bourgeoisie (and that the black power narrative’s connection to international struggles was largely symbolic and performative).

Rustin’s opponents didn’t fully comprehend what he was saying, because they didn’t recognize the latent continuity between (nationalist) black self-determination notions and an emergent class of black self-help gurus and black “enterpreneurial” liaisons to corporate America—both exploiting a fiction called “the black community.” It became Booker T. Washingtonianism (wearing a fashionable beret), with self-appointed stand-ins, in Reed’s words, “for a civically mute black population.”

Rustin has been reclaimed by the postmodern left more on account of his sexuality than his ideas, the latter of which ran counter to New Left and post-New Left identitarian ideologies. Rustin was gay, but this was irrelevant to his politico-strategic orientation. He was certainly aware of the difficulties and cross-racial grievances that were emphasized by Black Power advocates; but he also knew the dangers of emphasizing differences instead of seeking common ground and of the stylistic politics of macho belligerence in the face of a stronger enemy. More than that, he foresaw how easily an ethnocentric politics, underwritten by virtue-signaling moral one-upmanship (within a strict ideological frame), could be co-opted in a way that pulled stylistic radicals away from their professed class-consciousness.

Black Power was aimed, uncritically and unconsciously, yes, toward yet another politics of black uplift. Rustin, in “From Protest to Politics” (1965, linked above), wrote:

The decade spanned by the 1954 Supreme Court decision on school desegregation and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 will undoubtedly be recorded as the period in which the legal foundations of racism in America were destroyed. To be sure, pockets of resistance remain; but it would be hard to quarrel with the assertion that the elaborate legal structure of segregation and discrimination, particularly in relation to public accommodations, has virtually collapsed. On the other hand, without making light of the human sacrifices involved in the direct-action tactics (sit-ins, freedom rides, and the rest) that were so instrumental to this achievement, we must recognize that in desegregating public accommodations, we affected instituions which are relatively peripheral both to the American socio-economic order and to the fundamental conditions of life of the Negro people. In a highly industrialized, 20th-century civilization, we hit Jim Crow precisely where it was most anachronistic, dispensable. and vulnerable—in hotels, lunch counters, terminals, libraries, swimming pools, and the like. For in these forms, Jim Crow does impede the flow of commerce in the broadest sense: it is a nuisance in a society on the move (and on the make). Not surprisingly, therefore, it was the most mobility-conscious and relatively liberated groups in the Negro community—lower-middle-class college students—who launched the attack that brought down this imposing but hollow structure.

Rustin asked after the ultimate value of mere integration in commercial spheres when the majority of blacks—North, South, and West—lacked the economic power to take advantage of their “rights.” He also saw the direction of technological development—anticipating Harry Braverman’s thesis on deskilling by nine years—and all the ways that “monopoly capital” could simply absorb racial-uplift and self-help strategies. (Re-quoting and adding on):

I would advise those who think that self-help is the answer to familiarize themselves with the long history of such efforts in the Negro community. and to consider why so many foundered on the shoals of ghetto life. It goes without saying that any effort to combat demoralization and apathy is desirable, but we must understand that demoralization in the Negro community is largely a common-sense response to an objective reality. Negro youths have no need of statistics to perceive, fairly accurately, what their odds are in American society. Indeed, from the point of view of motivation, some of the healthiest Negro youngsters I know are juvenile delinquents: vigorously pursuing the American Dream of material acquisition and status, yet finding the conventional means of attaining it blocked off, they do not yield to defeatism but resort to illegal (and often ingenious) methods. They are not alien to American culture. They are, in Gunnar Myrdal’s phrase, “exaggerated Americans.” To want a Cadillac is not un-American; to push a cart in the garment center is. If Negroes are to be persuaded that the conventional path (school, work, etc.) is superior, we had better provide evidence which is now sorely lacking. It is a double cruelty to harangue Negro youth about education and training when we do not know what jobs will be available for them. When a Negro youth can reasonably foresee a future free of slums, when the prospect of gainful employment is realistic, we will see motivation and self-help in abundant enough quantities.

A politics based on political economy, and not ethnic identity, was necessary to overcome these obstacles, he said, because “in the present period we are dealing with practically no fundamental question in the minds of Negroes which are ‘Negro problems’—for what Negroes are interested in is decent housing, decent jobs, decent education and the right of participation in decision-making.” The same things all poor and working class people—the transracial majority—desire.

Already, in 1965, as the SNCC was preparing to break away toward Black Power, Rustin was criticizing the “‘no-win’ policy” of provocation. (Forgive me another lengthy quote, but it hits home.)

Sharing with many moderates a recognition of the magnitude of the obstacles to freedom, spokesmen for this tendency survey the American scene and find no forces prepared to move toward radical solutions. From this they conclude that the only viable strategy is shock; above all, the hypocrisy of white liberals must be exposed. These spokesmen are often described as the radicals of the movement, but they are really its moralists. They seek to change white hearts-by traumatizing them. Frequently abetted by white self-flagellants, they may gleefully applaud (though not really agreeing with) Malcolm X because, while they admit he has no program, they think he can frighten white people into doing the right thing . To believe this, of course, you must be convinced, even if unconsciously, that at the core of the white man’s heart lies a buried affection for Negroes—a proposition one may be permitted to doubt. But in any case, hearts are not relevant to the issue; neither racial affinities nor racial hostilities are rooted there. It is institutions—social, political, and economic institutions—which are the ultimate molders of collective sentiments. Let these institutions be reconstructed today, and let the ineluctable gradualism of history govern the formation of a new psychology.

Today, the frequency of American “interracial” marriage, as one example, doubled between 1980 and 2008 (from 6.7% to 14.6%), so this is not as remarkable now as it was during my time in the US Army (1970-1996), where, in this particular institution (arguably the most thoroughly integrated in the nation for decades), interracial marriages of all types were far more common than they were “on the outside.” The Army (far more than the other service branches, even) was (1) in many cases a class stepping stone in avoidance of poverty and in pursuit of skills, (2) matching black, brown, and white by class in a common environment, with common experience, a common professional idiom, and even common attire. The reconstructed institution, then, facilitated the “ineluctable gradualism of history [that] govern[ed] the formation of a new psychology.” Our own (military and very mixed) family is an example, apart from all that’s problematic about warmaking institutions.

What Rustin argued for—in 1965—was a political program that looked remarkably like that proposed during the Sanders campaigns of 2016 and 2020; in other words, a social democratic program (“The Freedom Budget for All Americans,” [emphasis added] prepared by Rustin, Randolph, and King) that applied to all citizens based on class, which would disproportionately affect black and brown people who were over-represented among the poor and working class, though not exclusive. The appeal of social democratic measures across “racial” lines held (and continues to hold) the greatest potential for any majoritarian political strategy (especially now that those lines are being redrawn).

Rustin, it must be said, bent the stick a long way; and his rejection of a variety of political tactics permitting greater tactical agility, informed by his faulty analysis of Democratic politics at the time, was probably an error (Cedric Johnson has written about this in his own critique of Back Power in its “racial-standpoint epistemology”).

Cedric Johnson

Crystal balls, then as now, were in short supply; but Rustin’s anticipation of Black Power’s devolution into an ethnic trickle-down economics (about as effective as the other kind) was positively prescient.

As Johnson noted, “counterproductive assumptions of black unity politics . . . have historically facilitated elite brokerage dynamics rather than building effective counterpower.”

Black Power, as an enthnocentric politics of performance was not only susceptible to reckless adventurism and police infiltration, it was entirely permeable to right-liberal technocratic managerialism. The black exceptionalism of Black Power was also, paradoxically, the black exceptionalism apparent in the now infamous Moynihan Report, over seen by Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Lyndon Johnson’s assistant secretary of labor, in which Moynihan said that black poverty was the result of a “cultural pathology” that differentiated it from “white poverty.” This echoed the BPP claim that while pathological, the urban “lumpenproletariat” was some kind of latent revolutionary mass. Technocratic managerialism would interact with Black Power exceptionalism, in the end, by these tendencies swimming toward each other until they were merged. The Negro again subsumed and negated the potpourri of actual black persons, and class was, again, eclipsed by ethnic self-help schemes begetting clientelism (and the production of an opportunistic black political class).

As the most “dangerous” of the Black Power advocates were picked off (with wide public support), the more “moderate” welcomed the approach of the technocratic establishment (with money in hand) and it’s embrace of “ethnically authentic” administrators.

As it turned out, Black Power militancy and the managerial logic of the Great Society were symbiotic. Figures as diverse as Newark mayor Kenneth Gibson and Black Panther Party co-founder Bobby Seale participated in and led anti-poverty programs. The Community Action Agencies provided established black leadership, neighborhood activists, and aspiring politicos with access, resources, and socialization into the world of local public administration. Moynihan later claimed that “the most important long-run impact” of the Community Action Program was the “formation of an urban Negro leadership echelon at just the time when the Negro masses and other minorities were verging towards extensive commitments to urban politics.” [italics added] Recalling the quintessential political machine of Gilded Age New York, Moynihan concluded that “Tammany at its best (or worse) would have envied the political apprenticeship provided the neighborhood coordinators of the anti-poverty programs.” Although Black Power evocations of Third World revolution and armed struggle carried an air of militancy, the real and imagined threat posed by Black Power activists helped to enhance the leverage of more moderate leadership elements, facilitating integration and patronage linkages that delivered to them urban political control and expanded the ranks of the black professional-managerial stratum. The threat of black militancy, either in the form of armed Panther patrols or the phantom black sniper evoked by public authorities amid urban rioting, facilitated elite brokerage dynamics and political integration. Instead of abolishing the conditions of structural unemployment, disinvestment, and hypersegregation that increasingly defined the inner city, Black Power delivered official recognition and elite representation. (Johnson)

Despite claims to the contrary by many “leftists” and “revolutionaries,” the American ruling class has always been bigger, stronger, and more tactically agile by orders of magnitude than utopian grouplets have been willing to acknowledge (mea culpa, mea maxima culpa). Reports of its death, as the saying goes, were greatly exaggerated.

End of Part 3

Quick afterword on the subject of race. Though I quote Reed, Johnson, and other from the left, because we are talking about political strategy, I have a slight, if not difference, then, expansion on the topic, that adds some context to the word and its evolution.

To explain “race,” we need to divide metaphysical worlds into pre-modern and modern, the latter of which also encompasses post-modern (which isn’t really “post” anything). Let’s call it old-world and new-world. The old-world, then, is in many respects completely different from our new-world; and here I’m not speaking chronologically, but philosophically — think “pre-Descartes, post-Descartes.”

Race, as understood by our present-day culture-war combatants, on both sides, is a thoroughly modern, new-world construct, which Reed and Johnson rightly identify as a scientific fiction. But I’m not a leftist in the same way, certainly not ideologically, which I’ll explain in the forthcoming episode. I’m a Catholic, neither the rad-trad nor the progressive type, the two of which engage in phenomenologically co-constituted debates that are also—equally, in my view—wrong. My views are more aligned with Iris Murdoch, Alasdair MacIntyre, Ivan Illich, and even J.R.R. Tolkien (who is widely misunderstood).

Old world was, in many respects, Platonist. Essentially, the spiritual precedes the material. We see this in Genesis, and even in J.R.R. Tolkien’s world-birth mythology, where spiritual beings sing the material world into existence. Forms—born in the celestial mind—precede their own incarnations. Second of all, all these forms exist in complementary relations to one another.

Some will say that race was invented by capitalism. That’s partly true and partly false. Modern conceptions of race emerged within the capitalist epoch, but there were former conceptions of something that translates into “race.” What capitalism gave birth to was “scientific racism” (or Reed’s scientific fiction) which has now undergone serial transformations within modern/”postmodern” epistemic frameworks. Ancient Greeks wrote about “race” with some frequency, and in a very “essentialist” fashion, though not universalizingly so as modern social Darwinists did (and do), with their talk of genes and evolutionary “fitness,” mystifying both. The old world had an account of these essences that’s totally alien to capitalism’s “social Darwinism” and late capitalism’s subsequent reactions against social Darwinism.

In Tolkien’s fiction (the literary kind), he spoke of races (humans, elves, dwarves, hobbits, et al), but he was using the word in the old world sense.

Race meant something over, under, around, and through . . . lineage, language, land, foods, customs, and deity/ies. In many cases, especially in and around the Mediterranean and North Africa, any one group (race) might contain a pretty diverse set of phenotypes (which we now identify with race).

Whoopi Goldberg got herself into trouble some time back by saying the Shoah (Holocaust) was not racially motivated, because the Jews were “white” like other Germans. This provides us an entry point, because Goldberg — Caryn Elaine Johnson, who took a Jewish stage surname — has inadvertently exposed everything that is incoherent about contemporary ideas regarding race. She’d seen pictures of European Jews and European Gentiles, and based on their “white” phenotypical similarities and our own cultural categories [check if you are (a) white (b) black ( c) Latino/a (d) Asian (e) Native American (f) Pacific Islander (g) Middle Eastern (h) Other], and she saw European Jews as “white.” Is “Jewish” a race? An ethnicity? A religion? What of secular Jews? What if she were to encounter black Jews (yes, there are)?

Ancient Greek writers saw race (a word meaning “roots”) as a group consolidated around lineage, language, land, foods, customs, and deity/ies, and when they wrote about various races and their essences, they attributed these essences to internal and external forces working together. Lineage, for example, is not determined by DNA tests, but through marriages (often of diverse phenotypes).

An example from the Hippocratic Corpus, around 350 BC, on the Scythian “race”: Scythians are fat and disinclined to work, says our writer, with red hair and red faces (from too much cold exposure), and their women have great difficulty getting pregnant. Pretty racist, eh? Scythians, by the way, were sort of Slavic by today’s lights, roaming around between Mongolia, Russia, and Turkey. In the same breath, our Greek race theorist notes that Scythian women taken as Greek slaves are trimmer, more vigorous, and more easily impregnated than their “free” counterparts to the North. Wait, what? Weren’t they essentially fat and lazy and nearly infertile? Well, Scythian men are averse to sexual intercourse because they have “cold bellies” and they spend to much time on horseback (watch out, all you horsemen). (Okay, it’s weird, but a reminder of why we can’t retroactively project our own ways of knowing onto people in the past.) Scythians are messed up, by Greek standards, because their essence is determined not merely by genos (which can be altered by marriage), but by land, climate, food, and even how they use their animals. (ht John Heers)

In the Torah, or Old Testament, Moses—an Israelite, working for an Egyptian (North African) monarch, takes the Cushite (a southern, “black” African) Tzipporah as a wife (Numbers 12). The Cushites were neither Egyptian nor Israelite, but once (black, by today’s account) Tzipporah marries Moses, she becomes, in the “racial” scheme of Hebrew writers circa 1400 BC, no longer a Cushite, but an Israelite. She retains a recognized history as a Cushite and a recognizable phenotype(which is irrelevant except for mundane purposes of recognition), which makes her somewhat unique among her new people, but she is re-racially determined by a new land, new foods, new customs, a new language, her incorporation into a new patrilineage, and a new deity. Race, in the old-world sense, also meant a common understanding of the good (similar to the way we think of “religion”).

Earlier modern and social Darwininst conceptions of race reduced “race” to “genetic” lineage and phenotype. So in a sense, Whoopi Goldberg’s racial blunder about Jews was (kind of) understandable. Even many anti-racists, especially of the permanence-of-racial-conflict variety, are also stuck with this conception of race — maybe a superficial touch of “culture” thrown in.

The truth is, Whoopi Goldberg, referring here to her show The View, where she also got into hot water on immigration issues (another story about phenotypes), has far more in common with interlocutors like Meghan McCain, Nicole Wallace, and Barbara Walters than she does with a black woman living in Stadium Heights in Durham, NC. Goldberg has assets totaling $60 million, she lives in a West Orange mansion in New Jersey, and she speaks the language of the film/infotainment industry. She eats the same foods as others of her class, shares their values, and like them has no real connection to land or or any day-to-day connection to climate (like a farmer, e.g.). In old-world terms, her race would be . . . oh, maybe . . . Infotainmentite.

Look at this stock “diversity” photo:

Members of the PMC would likely see themselves here, and “celebrate diversity” (where’s our Asian? our Arapaho? our Azerbaijani?). What I see are designer clothes, about a million dollars worth of dental work, a thousand dollars worth of coif, hundreds in cosmetics, and a lot of transient fashion sense. In other words, I see class (and youth). Not one of these people is “representative” of me or my neighbors or the vast majority of people in our town or our families. And not because of race.

Race, seen in the social Darwinian sense as lineage (misunderstood as “genes”) and phenotype (when did melanin, a biomolecular polymer, enter the pop vocabulary?), is not only the obsession of social Darwinist bigots, it’s become a cognitive default for professional anti-racists, who seldom challenge the reduction of race to genetic lineage and phenotype, but instead (rightfully) denounce anyone who puts the categories into a value-hierarchy and (wrongly) suggest that “white people” are inevitably racist (a kind of perverse cultural essentialism, which can be monetized as a moral product as well as politically exploited).

Yes, there are historical forces that are manifest today in sub-cultures as economic, cultural, sub-cultural, and “racial” differences. Life in Stadium Heights is far different than it is in West Orange or Anaheim. These differences were forged in economic and political strife, by the pursuit of “progress” and profit, by human frailty, by climate and soil . . . on and on. How far do you want to go back?

Jacques Maritain wrote, “It is as easy to disentangle these remote causations as to tell at a river’s mouth which waters come from which glaciers and which tributaries.”

Today, in the new-world, and even with these “cultural” and economic differences, the old-world understanding of race would have already merged us across phenotypes, based on our distanced relation to land and climate, our shared understandings under the aegis of corporate media, our acceptance of thoroughgoing dependence upon money to survive, our homogenized industrial food system, etc. etc. More so in recent years, as we’ve all been incorporated into the digital race.

The old-world said we have souls. We were more than the gears in a great machine, in a system, more than a race of “users” for a menu of software and apps. In this, I am old-world.

Many “progressives” are all still themselves the captives, even if derivatively, of social Darwinism’s race-reductions. On this, I am totally with Reed and Johnson.

Part 4 Forthcoming