The fallacy of 'technological' neutrality

as segue

My mother most emphatically insists that when she was expecting me she never thought of me as a fetus. And I remember a time when the fetus could be featured only in the kinds of books that also showed labia majora and pubic hair. But we are now overwhelmed with fetuses. I encountered one recently in a German ad for a Swedish car. Another one confronted me from the top of a circular urging me to discuss abortion with my candidate before giving him my vote. A pregnant colleague asked me to extinguish a cigarette. Why? Because she thinks that for the next six months she is the ecosystem for a fetus. (Barbara Duden, Disembodying Women, 1993)

This computer here on the table is not an instrument. It lacks a fundamental characteristic of that which was discovered as an instrument in the twelfth century, the distality between the user and the tool. A hammer I can take or leave. It doesn’t make me into part of the hammer. The hammer remains an instrument of the person, not the system. In a system the user, the manager . . . by the logic of the system, becomes part of the system. (Ivan Illich, Interview with David Cayley, 2004).

[I]t is not unreasonable to propose that the central and most “opaque” fetish of capitalism is nothing less than the machine. (Alf Hornborg, The Power of the Machine, 2001)

A phenomenologist, an epistemologist, and a Marxist walk into a bar . . .

I don’t know why other people study things, but I assume many of us do so for the same reasons. No doubt I’m driven by the concupiscence of my own curiosity, but below that apparent desire burns another.

It’s a little like the Tom Petty song: I’m “tired of myself, tired of this town.”

I read, study, and reflect to break the barrier of myself, or, in the herpetological spirit of this newsletter, to shed my skin. I need something Other. Then, in true graphomaniacal form, I peck out reflections for unknown Others in the hope of denaturalizing the same seemingly axiomatic beliefs under which I’ve labored and suffered in the past. This essay aims not to diagnose or cure, but to denaturalize.

I made an impulsive post on social media a few days ago: “There’s a case to be made for the Luddite destruction of robotics.” It was well-received according to the “likes,” albeit often with people’s own obsessive projections (like it was about Trump, as just one example). It’s no surprise it was well-received, not because of the “rightness” of it (to which I whimsically adhere), but because social media self-organizes, with a little algorithmic boost, into salons for the more-or-less like-minded.

I did, however, receive push-back from one interlocutor, for which I’m grateful. He wrote:

I think that the question of sabotage/expropriation is the fundamental one for modern human beings who are sympathetic to universal well-being.

Of course there is a case to be made for it… but it’s fundamentally a question of who controls the machine & to whose benefit it operates. Same thing is true of pipelines, water treatment plants, power grids, et cetera. I don’t think the toothpaste of technology is going back in the tube.

That said, there are mechanisms that can only be made to serve the interests of social dominance — those are mechanisms that should be seized & dismantled.

The thing is that when faced with the threat of expropriation, the dominant elite in the anglosphere has often resorted to sabotage themselves.

Again, gratitude. All of us need our thinking challenged, because (1) if we’re wrong, it needs pointing out and (2) even if we’re to one degree or another right (which I still think I am), there’s entirely too much shortcut thinking facilitated by meme-based, stick-and-move, egoistic, point-scoring “argumentation.” One of the technologically-wrought pathologies of our age is this contagious intellectual lassitude. ^^^The brother makes some good points, even where I disagree. But I’m obliged now to spell out those disagreements, and they all start in the bar where ^^^ those three folks went.

I’ll start with the material and hopefully progress through to the epistemological and phenomenological, then attempt a bit of synthesis. As indicated in the subtitle, this “neutrality” is not the main topic at hand, but an on-ramp. We’ll go from Hornborg through Illich and to Barbara Duden and, finally, to Byung-Chul Han.

I wrote a book called Mammon’s Ecology—The Metaphysic of the Empty Sign about the socio-material effects of money as a sign (in the semiotic sense), my thesis cribbed, with grateful attribution, from the groundbreaking work of Marxist anthropologist Alf Hornborg. Money as “ecosemiotic phenomenon” was a buttressing argument in his book, The Power of the Machine, cited the triple epigraph above. His main argument was about “machine fetishism.”

Fetishism is linguistic currency in the Marxist tradition, and as such it can be a little arcane to the uninitiated. I’m going to vernacularize it a bit, and just call it the “out of sight out of mind” phenomenon. Marx’s thing was “commodity fetishism,” and Hornborg is applying the same insight to machines themselves. Marx wrote (in Capital, Volume I),

As against this, the commodity-form, and the value-relation of the products of labour, within which it appears, have absolutely no connection with the physical nature of the commodity and the material relations arising out of this. It is nothing but the definite social relation, between men, themselves, which assumes here, for them, the fantastic form of a relation between things. In order, therefore, to find an analogy, we must take flight into the misty realm of religion. There the products of the human brain appear as autonomous figures endowed with a life of their own, which enter into relations, both with each other and with the human race. So it is in the world of commodities with the products of men’s hands. I call this the fetishism which attaches itself to the products of labour as soon as they are produced as commodities, and is, therefore, inseparable from the production of commodities.

Long story short, that gadget you buy appears as itself and as a price by which you can obtain it. What’s not apparent are the (unjust) social relations behind the gadget’s production. That social stuff is “out of sight and out of mind.”

I gave an example in Mammon’s Ecology, using the lithium battery that’s probably within inches of you right now as you read this (on your computer):

Your lithium batteries require cobalt. The Congolese cobalt mine employs a combination of fossil energy powered machines, cheap labor (child miners in this case), and deforestation to mine the cobalt. It results in sulfuric acid, arsenic and mercury in the surrounding air and water, cyanide as a waste product for milling, and the dumping of massive amounts of tailings onto adjacent land. In the Democratic Republic of Congo there have actually been a series of civil wars for control of these valuable minerals. And one hour of minimum-wage American labor is $7.50 an hour, whereas the minimum-wage Congolese makes $1.83 a day. This is unequal exchange expressed as an appropriation of time.

Out of sight out of mind.

Hornborg says that the out of sight out of mind phenomenon works in an especially sly way with technology, or machines. We tend to think that technology itself has no ethical content, and that any ethical content is added only by how we use technology.

I’m thinking now of Harriette Arnow’s classic novel The Dollmaker, in which Kentucky farm woman Gertie Nevels uses her pocket knife to open an emergency airway in her child’s neck to prevent him dying of whooping cough. Later in the novel, after she and her family have been economically forced into city life and factory labor, her husband Clovis, morally degraded by the “urban,” uses the same knife to commit a murder.

This is how we think of technology, because technology’s dead, right? It doesn’t do anything without our direction, so there’s no inhering ethical content apart from how it’s used.

The fetish character of the machine resides in its ability to present itself to our consciousness as a local achievement rather than as a product of the confluence of global flows.

—Alf Hornborg

“The machine,” writes Hornborg, “is represented as standing there, aloof and innocent, intrinsically devoid of significance.” Or, returning to our title, technology appears to be ethically neutral.

My social media interlocutor said, “it’s fundamentally a question of who controls the machine & to whose benefit it operates.” This is actually a point that could have been made by my comrades back in the day when I was myself a Marxist. That’s why Hornborg’s ideas are heterodox within the Marxist tradition—both academic and political.

As to my social media challenger, he did qualify his argument by saying, “That said, there are mechanisms that can only be made to serve the interests of social dominance — those are mechanisms that should be seized & dismantled.”

Setting aside the we-dreaming aspect of this political fantasy, the claim here seems to be that while some technology may inhere with “social dominance,” there are technologies which, in fact, are neutral (like Gerti Nevels’ knife), which is why I brought up lithium batteries as just one example of the toothpaste that’s escaped from the tube.

There’s a “turtles all the way down” aspect to our machines (or in Ivan Illich’s idiom, our “systems”). I’ll commend his book(s) to you for further elaboration, but Hornborg synthesizes semiotics, world-system theory, and thermodynamics to get us there. I’ll just thumbnail the thermodynamic (or ecological, or material) argument.

The thermodynamic problem afoot with “machines,” that is, they all rely on energy which is more of a “zero-sum game” than a “cornucopia,” the limitless energy delusions of radical technological optimists notwithstanding. The Second Law of Thermodynamics does not play. (This, in fact, is why I maintain that even the most stunning and seemingly irreversible technological changes we live with now are on a pretty short leash in historical time. The lights will go out, or capital will terminally disrupt the biosphere, or both at once.)

Let’s return now to Illich. In the quote above, he describes the difference between instruments and systems. Gertie Nevels’s knife is not like AI. The knife has that “distality.” We can use it without being incorporated into its logic, like a system does. It’s still an “instrument,” even in the hands of her homicidal husband. All one has to do to see this incorporation of the person by technology is observe anyplace where groups of people wait. They’re all zombie-locked into their “smart” phones.

Take away the fleshy, bodily, carnal, dense, humoural experience of the self, and therefore of the Thou, from the story of the Samaritan, and you have a nice liberal fantasy, which is something horrible. You have the basis on which one might feel responsible for bombing the neighbour for his own good.

—Ivan Illich

Illich uses the word logic. This is an epistemological claim. We’re changed fundamentally by systems-tech in terms of how we know. This isn’t projection or speculation. I read Illich (past and present tense) quite a lot, and I’ll quote here from his pamphlet, Energy and Equity, written all the way back in the Precambrian seventies, about cars:

The habitual passenger must adopt a new set of beliefs and expectations if he is to feel secure in the strange world where both liaisons and loneliness are products of conveyance. To “gather” for him means to be brought together by vehicles. He comes to believe that political power grows out of the capacity of a transportation system, and in its absence is the result of access to the television screen. He takes freedom of movement to be the same as one’s claim on propulsion. He believes that the level of democratic process correlates to the power of transportation and communications systems. He has lost faith in the political power of the feet and of the tongue. As a result, what he wants is not more liberty as a citizen but better service as a client. He does not insist on his freedom to move and to speak to people but on his claim to be shipped and to be informed by media. He wants a better product rather than freedom from servitude to it. It is vital that he come to see that the acceleration he demands is self-defeating, and that it must result in a further decline of equity, leisure, and autonomy.

Illich refers to “the feet and the tongue.” He was, for some time, a very earthy Catholic priest, and embodiment meant something important to him. What distinguishes instrumentality from systems is the degree to which a “tool” transfers power (surrenders autonomy) to a technocratic apparatus, to more machines and to the technocracy’s priesthood of experts.

It’s difficult to lay down a marker between Illich and his colleague, Barbara Duden—a German historian—as epistemologist and phenomenologist. For the last few years of Illich’s life, they worked very closely together; and their ideas aren’t contained within pre-established academic or philosophical corrals. Duden writes as an historian of perception in her book, Disembodying Women, which was the result of long conversations with Illich, in which each of them was transformed by new insights about the systematic-technological risk society.

If anybody should ask me what is the most important religiously celebrated ideology today, I would say the ideology of risk awareness—palpating your breast, or the place between your legs, in order to be able to go to the doctor early enough to find out if you’re a cancer risk. Why is it so disembodying? Because it is a strictly mathematical concept. It is placing myself, each time I think of risk, into a base population for which certain events, future events, can be calculated. It is an invitation to intensive self-algorithmization, not only disembodying, but reducing myself entirely to misplaced concreteness by projecting myself onto a curve. (Illich, Rivers North of the Future, 210)

In Duden’s book, she tracks, using the historian’s tools, the way it felt to be a pregnant woman in different periods. She wanted to know how women experienced themselves as pregnant bodies. The book is a fascinating read, and I’m not altogether sure why it hasn’t gained more notoriety, except that it’s difficult to grasp without stepping out of how we experience ourselves. (Or, more conspiratorially, after 1980, Illich’s books began deconstructing the messianic discourse of “the school as a pastoral institution capable of delivering the individual or society into some state of secular salvation,” they disappeared from the shelves. [Gabbard].)

Illich died at Duden’s house in Bremen, Germany; they were that close. They both studied the history of perception, and for those who are interested in Illich on this, you might start with H2O and the Waters of Forgetfulness, about which I’ve linked a short talk here. Duden’s reflections on phenomenological genealogy unpack the fallacy of technological neutrality, but far more comprehensively than the (excellent) materialist critique that Hornborg offers, and more systematically than Illich in the rise of the risk management society for which techno-neutrality is a kind of gateway drug.

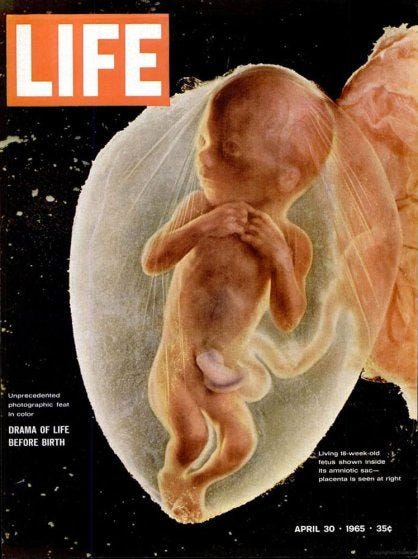

She begins her argument with the social impact of two images that became ubiquitous around the same time: a photograph of the earth taken from outer space, and the photograph of a dead fetus (that nonetheless came to be recognized as some “beautiful” representation of “life.”) These images were covers for LIFE magazine.

One image dislocated us all, and caused us to disappear in our embodiment. The other image disembodied women, by supplanting the proprioception of pregnancy with this from-the-outside view, aiming women at an image instead of all those carnal sensations.

Both images became possible only though the intervention of technology, and women themselves were confronted again—in the clinician’s office instead of by billboards and magazines—with the image of the ultrasound.

How did the unborn turn into a billboard image and how did that isolated goblin get into the limelight? How did the female peritoneum acquire transparency? What set of circumstances made the skinning of of women acceptable and inspired public concern for what happens in her innards? And, finally, the embarrassing question: how was it possible to mobilize so many women as uncomplaining agents of this skinning and as willing witnesses to the creation of this haunting symbol of loneliness? (Duden, 7)

In answering these questions, she discovered—in a way similar to Marx’s explosion of insights upon close examination of “the commodity”—the evolving rule of technocrats and experts, based on risk management, and its phenomenological migrations and colonizations.

To get there from here, we’ll begin with perception. The materialist account of perception—let’s take seeing as our example—involves light and a retina and an optic nerve. But we know from experience that this is not what “happens” in the experience of seeing. These motions and exchanges are “felt,” and more than felt in one’s consciousness, they are interpreted; and the interpretations are themselves embedded in socially-mediated experiences and expectations, which are further rooted in a kind of faith in the bases of those interpretations, without which we’d go mad overthinking every act of seeing. The act of seeing, phenomenologically, is a gestalt, a kind of indivisible symbolic yet visceral whole, and we go from one “seeing” to the next the way we ride a bike, with an habitual ease.

When we add a microscope or a set of binoculars, or interject technical simulacra (photographs or films, e.g.), the act of seeing is phenomenologically displaced. Certain symbolic constellations are dramatically exchanged for others. We come to perceive from an entirely different perspective, and these exchanges ramify epistemologically. The transformation of perception and the transformation of how-we-know are dialectically fused. This is what Duden is on about with these iconic images.

Once upon a time, we saw what we saw; but now, says Duden, “we see what we are shown.” And herein is the link between phenomenology and politics.

This habituation to the monopoly of visualization-on-command strongly suggests that that only those things that can in some way be visualized, recorded, and replayed are part of reality . . . The result is a strange mistrust of our own eyes, a disposition to take as real only that which is mechanically displayed in a photograph, a statistical curve, or a table. (p. 17)

This metastasized Cartesian distrust is on display everywhere we (ahem) look now. I refer again to anywhere people wait, faces glued to those infernal devices, oblivious to everything around them, even their ears stopped up with listening devices. (This is not, by the way then, neutral technology.)

Vision is dissociated from sight. This truth is difficult, because we’re the fish swimming in this dissociative water.

Duden goes on, with regard to pregnancy, to point out the in-obvious obvious: the experience of the unborn inside one’s own body is, by nature, invisible, accessible only through proprioception (and in the past those interpretive gestalts prior to women being technologically “skinned”).

The image of the fetus for LIFE magazine was taken by staff photographer Lennart Nilsson. In 1990, he used an electron microscope to make an image of human spermatazoa making their way to an egg. Nilsson was not a scientist, but a photographer—an image-maker. He made these images “not to verify a biological theory but to create a semblance of natural science representing his one visualization of ‘the beginning of human life.’” (p. 18)

In this “bestowing the status of reality on . . . visual appearances,” another phenomenon comes into being: the pop-X. A scientific concept or discovery (X) is internalized by the popular imagination in a way that is distinct from the material science itself. Duden became interested in the distinction between genes, understood scientifically, and what she named the pop-gene, or gene in popular imagination. Duden collaborated with Silya Samerski, a geneticist and sociologist, in describing the pop-gene. (Link to discussion with them, unfortunately and ironically, you’ll need an Adobe Flash Player to hear it anymore.)

What a gene is for a scientist can be described chemically with very little symbolic baggage. Good scientists who recognize the boundaries of their disciplines do not impute; they describe, and in a strictly limited way. In the popular imagination, however, the GENE took on a kind of mystical aspect. We’ve all seen the most far-fetched versions of this in fiction and film; but even in everyday use, the GENE has jumped the fence of science as it was married to another mindset underwriting the “risk management society”: statistical probability. The symbolic gestalt of perception, now distilled through “a photograph, a statistical curve, or a table,” has displaced our gaze perpetually to “the future,” and with it a state of chronic anxiety. Duden describes the risk management society as the driver of a car going very fast, who can’t afford to look at what’s nearby because her focus is constantly on some point on the road ahead where she’s not yet arrived. In this matrix of anxiety, insert the pop-gene, not only as some formative little god, but as a stream of dangers (threats).

In this probablistic world, we require technology and the experts in this technology, to avert the perceived risks. Not desire, need! We experience the desire for control—even when no real threat is there except as some imagined probability—as the need, the urgent necessity, for a technocrat or an expert with his or her machines and systems and specialized emanations.

It is genes, we are told, which determine the health of our children, cause our early death or early dementia. Therefore, only those ones who allow geneticists to educate them are considered capable of autonomous and responsible thought and action. On the basis of observed and recorded genetic counseling sessions Samerski demonstrates the paralyzing and incapacitating effects of professional education on genes and risks. Thereby, she questions a dogma of our time: that being counseled into scientific knowledge necessarily leads to freedom and autonomy. (Samerski, translated from Das Alltags-Gen)

Samerski calls this “the perversion of autonomy: Namely, the freedom to think and act by oneself.”

When this anxiety is generalized, those who refuse the probabalistic frame, the anxiety, and the control, who refuse to treat their lives like the fast car, are pathologized, even demonized. Some will recall that during the height of pandemic panic, Girogio Agamben, an Italian philosopher, found himself attacked and ostracized from the establishment, even the left of which he was a part, when he critiqued the responses to the coronavirus pandemic, written precisely from the perspective here of Duden and Samerski.

In this critique, he pulled together three key ideas: biopolitics, state of exception, and bare life.

Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben’s concept for life that has been exposed to what he terms the structure of exception that constitutes contemporary biopower. The term originates in Agamben's observation that the Ancient Greeks had two different words for what in contemporary European languages is simply referred to as ‘life’: bios (the form or manner in which life is lived) and zoē (the biological fact of life). His argument is that the loss of this distinction obscures the fact that in a political context, the word ‘life’ refers more or less exclusively to the biological dimension or zoē and implies no guarantees about the quality of the life lived. Bare life refers then to a conception of life in which the sheer biological fact of life is given priority over the way a life is lived, by which Agamben means its possibilities and potentialities. Suggestions made in 2008 by Scotland Yard and the Institute for Public Policy Research in Britain that children as young as five should be DNA typed and their details placed in a database if they exhibit behavioural signs indicating future criminal activity is a perfect example of what Agamben means by bare life. It reduces the prospects of the life of a particular child to their biology and takes no interest in or account of the actual circumstances of their life. (Oxford Reference)

Biopolitics is a Foucauldian category, meaning political power exercised directly over the carnal body.

State of exception is a category described (and even endorsed) by German philosopher Carl Schmitt (who eventually became a Nazi). A state of exception is when the governing apparatus suspends normative/constitutional protections of personal autonomy to address some “emergency.”

Placed on a statistical grid, bare life becomes a number, a pure utilitarian calculus. X number of people will probably live and Y will probably die if we do Z. No account taken of any actual living person.

We saw all this with the pandemic response, and the way it was enthusiastically embraced, to such a point that those skeptical of the response were anathematized as (probabalistic) dangers themselves. People not only welcomed the limitation of their own autonomy, they vigorously promoted its imposition on everyone else. Fear translated into a desire, experienced as a need, for control. Sweden refused the restrictions, and at the end of the day, their statistics (there it is again, this is what determines truth) were no worse than those who cracked down. This hasn’t convinced the public—with its pop-genes and its eye down the fast-road for potential risks—that such measures were neither necessary nor beneficial. We have embraced biopower, and with it an entire technocracy to enforce it.

This was even truer of the so-called left than it was of the right. In fact, the often superficial account of personal rights on the libertarian right at least pre-attuned them to the dangers of constantly feeling endangered. The rest of us, not from the right, who likewise came to criticize these measures, never had our arguments addressed—except in the terms of probablistic technocratic anxiety or simple guilt-by-association attacks. (“You’re right-wing now.” [see contamination narratives])

The social body constrains the way in which the physical body is perceived. The physical experience of the body, always modified by the social categories through which it is known, sustains a particular view of society. There is a continual exchange of meanings between the two kinds of bodily experience so that each reinforces the categories of the other.

—Mary Douglas

This is understandable, because the dominant episteme of our time is displaced embodiment, of not trusting our own senses, of “bestowing the status of reality” on images, statistics, and tables. To do otherwise is utterly counter-intuitive, because our intuitions have been so thoroughly formed by technology and technocratic management. We don’t trust ourselves or the evidence of our senses. We do trust statistics. We claim to value personal choices—even the most perverse definitions of it—but we want those choices to be “informed,” presorted by the priesthood of experts, so that we can optimize ourselves and those around us, so we can avert all those imaginary risks.

Aha! I hear some say. We have you now! Those risks are real!

Actually, they’re not. Risk is never real. That is exactly the point. By definition, risk is a possibility, an anticipation, not an actuality. Risk is only real in the oblique truistic sense that any action can go awry. This is pretty prosaic, certainly nothing upon which to base one’s life (unless life is you driving that fast car). Then the question becomes, risk (or possibility) of what? And how is that what identified? Statistics perhaps. Statistics said I was in mortal danger (as a septuagenarian) from coronavirus, and that recurrent vaccination would protect me from that danger. This was a statistical claim upon which the “status of reality” had been “bestowed,” and yet, in spite of the vaccinations and my own personal prophylactic actions (masking and so forth), I contracted Covid-19 (contra statistics) and survived quite nicely (contra statistics). I remember a line from the delightful television series, Stranger Things, where the Sheriff tells a mother that ninety-nine percent of the time, missing children come home on their own, to which she responded, “What about the other one percent?”

This is the distinction between statistics and reality.

Obviously, people have always avoided apparent dangers. Anyone who’s ever stepped in a yellow jackets’ nest will become a bit more watchful about leafy crevices at the base of trees during warm seasons (author raises index finger). But women have had successful pregnancies since women have existed, prior to and without understanding that pregnancy—a natural phenomenon—as interpreted for them through ultrasounds and genetic testing.

Some of my fellow Christians, based on this technocratic episteme, might say that biopolitical measures are simply the application of charity writ large. I have to disagree. The state is not a person, and the charity described in the Gospels is extremely personal. In fact, this is a diversion of the Christian obligation to love onto a conveniently impersonal entity. (My longer argument about that is here.)

Even my own church (Roman Catholic) has copped to this, and with it a new idol called “life,” which maps perfectly onto “bare life.”

It would be silly to consider this idolatry of life as a consequence of noisy disputes about Supreme Court decisions, Constitutional amendments, and congressional proposals. The growing ecumenical consensus about the sacredness of life is better understood as an aspect of a surreptitious shift in social and medical management concerns about the importance of “survival.”

—Barbara Duden

There is no more vain endeavor, as an end in itself, than survival. We don’t save lives, even though we may prolong them. This is a “bare life” precept. Alive (+), dead (-). Which serves as the basis, like zeros and ones in digital programming, for a substratum code.

In the “Instruction on Respect for Human Life in Its Origin and on the Dignity of Procreation,” penned by then-Cardinal Ratzinger in 1988, he wrote about “the conclusions of science regarding the human embryo provide a valuable indication for discerning by the use of reason a personal presence at the moment of the first appearance of a human life.” He then went on to (erroneously, in my view) justify the treatment of this embryo as a neighbor based on the parable of the Good Samaritan, as well as “the least of you” referenced as brothers and sisters in Matthew 25:40. (In fact, Luke 10 and the Parable of the Samaritan were paradigmatic for Ivan Illich in his interpretation of the Gospels, and that interpretation, with which I agree, runs completely counter to the way Ratzinger used it. For a comprehensive interview with Illich on this, listen here.)

Duden says, in the more secular (and Agambenesque) sense, we have “reduced flesh to data.” She was struck when she observed, in Harlem years ago, a newly arrived, pregnant, Puerto Rican mom, who was on her sixth pregnancy, with four children already, and seven siblings. The woman was directed by a local welfare worker to a storefront clinic run by a foundation for an interview, where she was confronted with a well-meaning young white woman, accompanied by a sociologist. They began by showing this woman pictographs and diagrams to tell her what was going on inside her own body and what kinds of risk were associated with it. Their goal was to convince her to do prenatal testing. They went at her for an hour, but she wasn’t buying it, and the graphs did nothing but confuse her.

Wrote Duden, “The thick circle the counselor penciled far down on the bell-shaped curve did not touch her . . . what I am trying to understand is the difference the encounter with a professional makes for Maria and the degree to which it removes her from the way her mother experienced the body.” (p. 27)

Maria wasn’t someone who’d had serial miscarriages or ectopic pregnancies. She wasn’t addicted to crack. Maria wasn’t, figuratively speaking, walking in the woods near yellow jackets’ nests. She was healthy, experienced, gravid woman. And yet, these experts wanted to create a dependency upon themselves, to chain her psychologically to a grid of technocratic monopolies by altering her perception, her way of living in her own skin, by transforming her body into a menu of risks.

This medicalization is but one facet of the risk management society. The biggest and most powerful sectors of today’s economy are FIRE—finance, insurance, and real estate. Insurance is the perfect exemplar of our capture by the risk management society.

Vaccinations are in the news again, because Trump chose Robert F. Kennedy Jr. to be his Secretary of Health and Human Services. RFK is a peculiar bird, no doubt, but of all his peculiarities (among them some very righteous legal actions related to environmental justice), his stand on vaccines is what aroused anti-Trump zealots. (I am NOT NOT NOT a fan of Donald Trump, okay; I’m just not making a career of anti-Trumpism. That buffoon will not rent a room in my head.)

I wrote about the general stupidity and the political incompetence of Democrats here, but once again, Obsessive Anti-Trumpsim will promote biopolitical power as a weapon against their demonic idol (via RFK), further consolidating the power of the very people they claim to oppose.

Canadian David Cayley wrote in October 2020, as the pandemic began to tail off:

Many preconditions converged in a perfect storm with the onset of COVID‑19. Apocalyptic fear, sanctification of safety, heightened risk awareness, glorification of management, habituation to a state of exception, the religion of life and the fear of death — all came together. And, together, they have made it seem perfectly obvious that total mobilization was the only possible policy. How could any politician have resisted this tide? But recognizing the force of the safety-at-all-costs approach shouldn’t prevent us from looking its consequences in the eye.

Mortality will increase from all the other illnesses that have been forced to take a back seat. Many small and even large businesses will fail, while a few gigantic ones, like Amazon, will prosper even more mightily. Small businesses add colour and conviviality to our neighbourhoods and cannot be replaced by drones and trucks dispatched from distant warehouses. Jobs and opportunities will be lost, predominantly among those who are young and least established, the so‑called precariat. Civil liberties will suffer, as they already have. At the beginning of the crisis, for example, the federal government tried, unsuccessfully, to give itself broad powers to spend, tax, and borrow without consulting Parliament. Shortly afterwards, the Alberta legislature passed Bill 10, which authorizes, among other things, the seizure of property, entry into private homes without warrant, and mandatory installation of tracking devices on phones. Authoritarian governments, like Hungary’s, have gone much further in consolidating and aggrandizing power under the cover of emergency. Experience shows that all of these new powers, once assumed, will not be readily relinquished. Habits of compliance, developed in the heady days when we were “all in this together,” may prove equally durable.

We are seeing the beginnings of a thoroughgoing virtualization of civic life, not all of which will end with the pandemic. Writing in The Intercept, Naomi Klein wittily called this development the Screen New Deal. Among her evidence: the announcement that the former Google CEO Eric Schmidt will chair a blue-ribbon commission charged with “reimagining” New York. The work will focus, Schmidt says, on telehealth, remote learning, broadband, and other “solutions” that “use technology to make things better.” New York has also announced a partnership with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to develop “a smarter education system.” In doing so, Andrew Cuomo called Bill Gates “a visionary,” while asserting that this is “a moment in history where we can actually incorporate and advance [his] ideas.” Do we really need “all these buildings, all these physical classrooms,” the governor asked rhetorically, given “all the technology” now available. And let’s not forget that Mark Zuckerberg has been in Washington promoting the saving role of technology in a world where people are afraid to get close to each other.

So this is the heritage: the possibility that the deaths averted by lockdowns will be offset by the deaths caused by them; spectacularly indebted governments whose deficits may threaten basic state functions; increased surveillance; reduced civil liberty; lost jobs and ruined careers; a frightened, more pliable citizenry; and an economy that has shrunk in the worst possible way by casting off the poorest and the weakest — a terrible irony for long-time advocates of degrowth, including me.

The late French philosopher Jacques Ellul developed the concept of technique. Technique has been translated wrongly two different ways. First, confusing it with its English doppelganger, like “the technique I use to cast with a spinning reel.” Nope, not that. Second, technology. Okay, that’s closer, because for Ellul, energy-slave machinery was part of the equation. In fact, what he meant, in the recondite manner of the French, was the gestalt (that again) of material gadgets, human subordination to them (lack of distality), the way this relation manifested in the mind as natural, and the manner in which these together produced a kind of popular idolatry of, in his case, efficiency. (Later, we’ll talk about achievement as another insatiable idol.)

Disembodiment is a phenomenological side effect of technique, of our incorporation into machinic “systems” and matrices.

“Your brain lights up,” begins an ad, followed by a “when . . .” A brain doesn’t light up, but we believe it does, because there’s a machine attached to someone’s head that lights up with a machinic image. We’ve “bestowed the status of reality” on the image.

How does the current digitally-amplified and accelerated version of technique appear to us (managerially and popularly) in symbolic assemblies? Then how does it “feel”? One answer is, as the compulsion to self-optimize. Once we’ve adopted a standpoint “from the outside looking in,” so to speak, once you’ve disembodied, “the” body becomes first an object, then a project. An image to be refined, a machine tuned up for maximal performance.

The violence of positivity does not deprive, it saturates; it does not exclude, it exhausts.

—Byung-Chul Han

And so we come to Byung-Chul Han, a Korean-born German philosopher and critical theorist.

Before we do that, remember Foucault. He’s been hovering in the background here. He’s the person most closely associated with the concept of biopolitics. Foucault’s thought was challenged by Illich, even as they trod the same ground (in their suspicion of modern certainties and their critiques of institutions). In particular, Illich implicitly criticized Foucault’s notion of governmentality as it relates to biopower. (For those interested in this rabbit hole, I recommend Tim Christiaens “Ungovernable Counter-Conduct: Ivan Illich’s Critique of Governmentality.”) (Foucault and Illich, for all their similarities, had deep metaphysical differences. Foucault was a Nietzschean, and Illich a Christian.)

“Foucault’s own work,” writes Christiaens, “is remarkably silent about the intersections of power, knowledge, and subjectivity beyond Europe, and the philosopher has often overlooked the role of the colonies in shaping Western modernity.”

Illich and Foucault were both preoccupied, like Byung-Chul Han, with the question of how power works. (Han is, like the late Illich was, a Catholic intellectual.)

In some sense, Han’s theses, like Foucault’s, are metrocentrically restricted (Illich, Duden, and Hornborg were far more attuned to life in “peripheral” societies), inasmuch as his philosophical critiques are preoccupied with the predicament of the metropolitan subject. Like all who decry, in one manner or another, the epoch of digital de-industrialization, he tends to overwrite the stubborn fact that industrial and brute labor, as well as pillage (primitive accunmulatoin), are still going on somewhere, including to make the things necessary to develop digital infrastructure. (Data centers, AI, and cryptocurrency are already two percent of global electricity demand, and this demand is increasing exponentially. There’s Hornborg’s themrodynamics again.)

It’s fine, this metrocentrism, it just needed saying. Everything doesn’t have to be universally applicable to be worthy of our critical attention, and there’s no doubt that the plague of digital life is still spreading, or that metropolitan life has profound knock-on effects on those beyond the industrialized metropole. I write often about the US. That’s because I live here. It’s what I know. Byung-Chul Han lives in metropolitan Europe, and as far as his critiques go, they very much do describe present-day metropolitan subjects.

Han directly critiques the concept of biopolitical power, not as flawed, but as increasingly outdated. He believes we (metropolitans) have passed into an even more sly and alienating form of power— the psychopolitical. (Economist Yanis Varoufakis has a proximate political theory, with a neo-Marxist gloss, which he calls technofeudalism.)

Digital technology has ramified, according to Han, in conjunction with neoliberalism, into a politico-economic web that no longer requires the kind of direct incarnate control of days past (obviously, we’re not talking here about a Congolese cobalt mine, which does employ hard biopolitical power). This transition to psycho-control was exacerbated and accelerated by the pandemic, but it was already in train beginning with the deregulatory regimes from Carter-Reagan-Thatcher-Deng-Microsoft onward.

Certainly, the regime of biopower (exploitation from outside) and psycho-power (self-exploitation) still overlap, as the latter advances. History doesn’t advance by stepping from stone to stone, but in streams and tides of multilectical flow. Han is pointing to the condition increasingly experienced in a society now ultra-atomized by digital technology. We can see (and feel) this self-exploitation everywhere. The self-optimizing episteme is a self-exploitative regime. The outside/Other master is being supplanted by the self as both master and servant in a Regime of Achievement. That Regime of Achievement, in turn, has created “The Burnout Society.”

In some ways, Han suggests, we’re also leaving behind (I’m skeptical) the “immunological society” that peaked during the pandemic state of exception. From his first chapter in The Burnout Society:

Every age has its signature afflictions. Thus, a bacterial age existed; at the latest, it ended with the discovery of antibiotics. Despite widespread fear of an influenza epidemic, we are not living in a viral age. Thanks to immunological technology, we have already left it behind. From a pathological standpoint, the incipient twenty-first century is determined neither by bacteria nor by viruses, but by neurons. Neurological illnesses such as depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), borderline personality disorder (BPD), and burnout syndrome mark the landscape of pathology at the beginning of the twenty-first century. They are not infections, but infarctions; they do not follow from the negativity of what is immunologically foreign, but from an excess of positivity. Therefore, they elude all technologies and techniques that seek to combat what is alien.

The past century was an immunological age. The epoch sought to distinguish clearly between inside and outside, friend and foe, self and other. The Cold War also followed an immunological pattern. Indeed, the immunological paradigm of the last century was commanded by the vocabulary of the Cold War, an altogether military dispositive. Attack and defense determine immunological action. The immunological dispositive, which extends beyond the strictly social and onto the whole of communal life, harbors a blind spot: everything foreign is simply combated and warded off. The object of immune defense is the foreign as such. Even if it has no hostile intentions, even if it poses no danger, it is eliminated on the basis of its Otherness.

Recent times have witnessed the proliferation of discourses about society that explicitly employ immunological models of explanation. However, the currency of immunological discourse should not be interpreted as a sign that society is now, more than ever, organized along immunological lines. When a paradigm has come to provide an object of reflection, it often means that its demise is at hand. Theorists have failed to remark that, for some time now, a paradigm shift has been underway. The Cold War ended precisely as this paradigm shift was taking place. More and more, contemporary society is emerging as a constellation that escapes the immunological scheme of organization and defense altogether. It is marked by the disappearance of otherness and foreignness. Otherness represents the fundamental category of immunology. Every immunoreaction is a reaction to Otherness. Now, however, Otherness is being replaced with difference, which does not entail immunoreaction. Postimmunological — indeed, postmodern — difference does not make anyone sick. In terms of immunology, it represents the Same. Such difference lacks the sting of foreignness, as it were, which would provoke a strong immunoreaction. Foreignness itself is being deactivated into a formula of consumption. The alien is giving way to the exotic. The tourist travels through it. The tourist — that is, the consumer — is no longer an immunological subject. (Han, The Burnout Society)

A lot to unpack there, and I’ll leave it to Han’s book to do that in detail. We’ll just hit a few highlights.

Again, he overstates (imo) his case, but not in such a way as to belie it. We’re not living in a state of either-or, but both-and. I wrote recently about a kind of immuno-logic or contagion-narrative, related to the manipulation of disgust and how this actually flourishes on the internet. We’ve developed the tendency—just as Duden describes with regard to tables, images, and statistics—to bestow upon cyberspace the status of reality. (Admittedly, my forays into digital space are pretty atypical and avocational, inasmuch as my own predispositions run to philosophical, self-critical, political, and platform-critical stuff like we’re discussing here. The vast majority of internet denizens are, in fact, caught up in the very things Han describes, especially those who “work” there.)

Foucault’s concept of biopower emphasized ideological categorization, wherein we can see Duden’s and Illich’s “medicalization,” based on the subsumption of the carnal body by technocratic statistics. Biopolitics, says Han, placed an emphasis on the body as a resource for productive output (industrial economy). whereas the service/digital economy aims more at control of the mind as critical resource for productive output.

Han is certainly aware, as a critic of capitalism, of the conditions of Congolese mine-workers and the women slaving away on the corridor maquilador. His emphasis on the digital turn may not highlight those conditions, but he says himself that the political and economic import of this transition from biopolitics to psychopolitics is based on the undeniable fact that the economy is now controlled by those not engaged in material production.

“[I]mmaterial and non-physical forms of production,” he writes, “are what now determine the course of capitalism.”

“The ring (financialization) and Sauron (neoliberalism) are one.”

What now has to be optimized for production (even as we treadmill our way to body-project optimization in our “spare time”) are “our psychic and mental processes.” Han says biopower has been superseded by psychopower, but I’ll suggest that it’s just been super-added. Most of our information on how to optimize the body-as-project (no longer for work, but for the recognition we’ve lost through ultra-atomization as well as in response to those fears identified by Duden) comes through the same cyberspace where many now slave away, with themselves as overseers.

“The subject of performance, who claims to be free, is in reality a slave. He is an absolute slave, insofar as without any master he willingly exploits himself.”

—Byung-Chul Han

Hegel’s master-slave dialectic requires the resistance of the Other to overcome in the struggle between recognition and self-assertion. The cyber-worker, the techno-feudal subject, is his or her own overseer, driven ever forward by the idol of Achievement. The exploited yet stubbornly contentious union worker has been replaced by the self-managing, self-exploiting entrepreneur. What does your Linked-in profile say? Have you successfully marketed yourself?

Two keywords for Han (in his Heideggerian/Marcusean idiom) are negativity and positivity. The “entrepreneur,” or the job-hunting manager is unlike the union worker, perpetually half a heartbeat away from a fuck-you for the boss, the worker requiring “negative” (outside) power to overcome her. The entrepreneur/PMC worker has become a salespersons, and the product is him- or herself. Power is exercised “positively,” the self-seller incorporating that positivity.

This post-Foucaludian “positive” power is only possible via the (technological) destruction, or atomization, of past forms of cultural restraint and the dissolution of colocational-community traditions. (Echoes of TS Eliot)

The negativity of repression and discipline (Foucault) isn’t nearly as effective, says Han, as “activation, motivation, and optimization.” Allo-exploitation is giving way to auto-exploitation.

It proves effective because it does not operate by means of forbidding and depriving, but by pleasing and fulfilling. Instead of making people compliant, it seeks to make them dependent. (Han, Psychopolitics)

Auto-exploitative self-optimization is like desire more generally. Without any limits or guardrails, it’s potentially infinite. The goalposts are always being moved back, because there is no perfect version of you or me. It’s a teleology of the unreachable. We’ve become the driver of the fast car, always fixed on the ever receding point ahead, and rendered incapable of anything like a contemplative gaze, a rest, a Sabbath, a reflective luxuriation in the wholeness of narrative. Our lives become one-rapid fire point-in-time after another, which leads to burnout—a sense of psychic fatigue, of loneliness, of depression. One is reminded here by Han of the theses of Illich and Paul Virilio with regard to the oppression of speed, of the “speed-stunned imagination” (Illich).

Performance, in Han’s sense, is twofold: the performance of an actor, which corresponds with self-marketing, and, as such, transforms us into narcissistic subjects (Echoes of Christopher Lasch); and performance in achievement, which burns us out. In both aspects, there’s an exaggerated self-reference, and with it a loss of identity. In the past, identity (self-understanding) was based not only on phenomenological experience, but on intersubjective exchanges of recognition, confirmation, correction, and direction with others (in the enfleshed, relational sense). In cyberspace, relationships are replaced by connections. In a kind of downward spiral, the narcissistic loss of identity translates into the loss of the ability to love. “Love” itself has come to mean—and this is why so many marriages fail, in my view—“finding oneself in the other.” (Some compare Han to Slavoj Žižek.) Actual love is a rupture of the self, not the mirror, but the shattering of the mirror.

Han believes that the inability to love caused by the narcissistic loss of identity (the loss of “the encounter with the other”) is the source of many so-called “disorders,” like depression, ADHD, and obsessions/compulsions. He thinks we may have passed yet again, from Illich’s instrumentality to systems, into yet another accelerating phase, a hyper-cyber-digital phase.

Han doesn’t ignore the material foundations. Remember, he names the age using an economic term, neoliberalism, the reorganization of political economy as a global market, unregulated for capital and highly regulated for labor. In this milieu, the metropolitan subject is now required to repeatedly re-train and re-configure him- or herself, to duck and jab through the restless dynamism of capitalist creation and destruction, leaping from one niche to another in a paradoxical world of innovative proliferation and new forms of scarcity.

The “negative” hard power of which Foucault spoke is replaced by the “positive” soft power of achievement, which creates its opposites in every failure to meet these internalized and constantly receding goals.

We are suffering, says Han, from “an excess of positivity.”

The complaint of the depressive individual, ‘Nothing is possible,’ can only occur in a society that thinks, ‘Nothing is impossible.’

-Byung-Chul Han

(I’d be very interested to read Erik Baker’s Make Your Own Job, btw.)

Modernity, especially late digital modernity, says Han, is not a pro-gression for the human psyche, but our re-gression to an animal-like state of defensive hyper-attention (caught between danger and achievement) that forecloses a state of contemplation (something now unimaginable to many).

The attitude toward time and environment known as ‘multitasking’ does not represent civilizational progress. Human beings in the late-modern society of work and information are not the only ones capable of multitasking. Rather, such an aptitude amounts to regression. Multitasking is commonplace among wild animals. It is an attentive technique indispensable for survival in the wilderness . . . The animal cannot immerse itself contemplatively in what it is facing because it must also process background events. [for survival, SG] (Han, The Burnout Society)

The old disciplinary world of lunatic asylums, workhouse barracks, and factory floors is being edged out by the internalized “achievement” regime of “fitness studios, office towers, banks, airports, shopping malls, and genetic laboratories.” (Han)

For Slavoj Žižek, the postmodern subject, with the absence of metanarratives on the one hand and the loss of the contemplative state on the other, oscillates between narcissistic projects (self-as-project), obsessions, technological (porn, video games, etc.) or pharmacological self-medication, experimenting with alphabetized identities, compulsive cycles of consumption, spiritual fads, and so forth. (In addition to spiritual fads, we might add instrumental and-or therapeutic adaptations of longstanding religious traditions.) Now, for the Lacanian Žižek, the concept of “surplus enjoyment’ figures in here, with regard to how our desires are engendered and harvested. (The white liberal who takes a perverse “enjoyment” out of constant self-flagellation about his or her privilege, e.g.) These are the coping mechanisms for people trapped in the freedom of superficial “choices.” We’re too far down our own particular rabbit hole here to burrow our way into Žižek’s, but these ideas correspond to Han’s in interesting ways.

What Žižek and Han would say is that in the past, under all disciplinary regimes, we knew we were getting shit upon by power, we knew the ways in which we were undoubtedly unfree. What’s changed now is that we think our unfreedom is freedom.

“Marx already said it,” Han declared in an interview, “individual freedom is the cunning of capital. We believe that we’re free, but deep down, we just produce, we increase capital. That is, capital uses individual freedom to reproduce. That means that we — with our individual freedom — are the sexual organs of capital.”

Enough.

Let me rewind now, back to my interlocutor who provoked this journey. You’re absolutely right, sir, that the toothpaste isn’t going back into the tube. More problematic still, we don’t merely learn the dominant ideology, we’re born into it. We haven’t been indoctrinated so much as infused. And yet, we know . . . somewhere down there . . .

Who among you hasn’t felt overwhelmed by too many “choices”? Who hasn’t been driven from one frantic point to another in a way that makes the Now feel like a bother and a loss? Who hasn’t experienced a vacation that felt like more work than work? Who hasn’t been the captive of the idea that life’s highest purpose is to cram in as many “experiences” as possible? Who hasn’t at some point, when confronted by beauty and awe, tossed aside the leisurely contemplation of it, to snap a selfie and move on? Who has not experienced that kind of subclinical buzz of anxiety running through our days, days that trail off like the highway scenery we didn’t see as we speed ahead, eyes always forward? Who hasn’t self-medicated or been caught up in cycles of obsession? Who among us hasn’t sometimes surrendered our consciousness to the risk management society? Felt that constant state of emergency? Who hasn’t been disembodied by machines and management and therapies? These are the pathologies of the age, an age in which we’ve lost the capacity for contemplation, for participation in the given, the gift.

It’s okay to be useless. We should all try it.

Sweden actually had fairly robust jobsite safety restrictions & sick leave to mitigate spread before it led to the health system being overwhelmed… and that's why they didn't need to have extreme, counterproductive lockdowns like they had in Europe. At least this is what my Swedish friends tell me.

Nothing disgusted me more than to see workers forced to wear PPE & get inoculated because they had to serve restaurant patrons on jobsites whose owberst refused to enforce minimal precautions for staff. Also, the health department literally copy & pasted our city's chamber of commerce's