Final installment.

The ultimate commodity under late capitalism is the human subject itself: sliced into infinitely customizable, profitable, and exploitable identity markers.

—Tara Van Dijk

Let’s begin by talking about race, wealth, and income. (WARNING: statistics!)

The top twenty-five (not percent) richest American households are all “white.” Between them, they have accumulated 2,516, 200,000,000 (lets call it 2.5T). Household wealth overall is $160T, so when you subtract the top 25 from total US households, 23,684, 960 households remain. Twenty-five households among almost 24 million, then, becomes statistically insignificant as a “racial” demographic, but not as an economic one. With this minor population subtraction of .0000010555% of total households, that hold 1.5% of all wealth, “white” wealth, 60% of the population ($93T), drops by 1.6%, meaning that .0000010555% population skews the “race” numbers by a factor of 1,421,127.

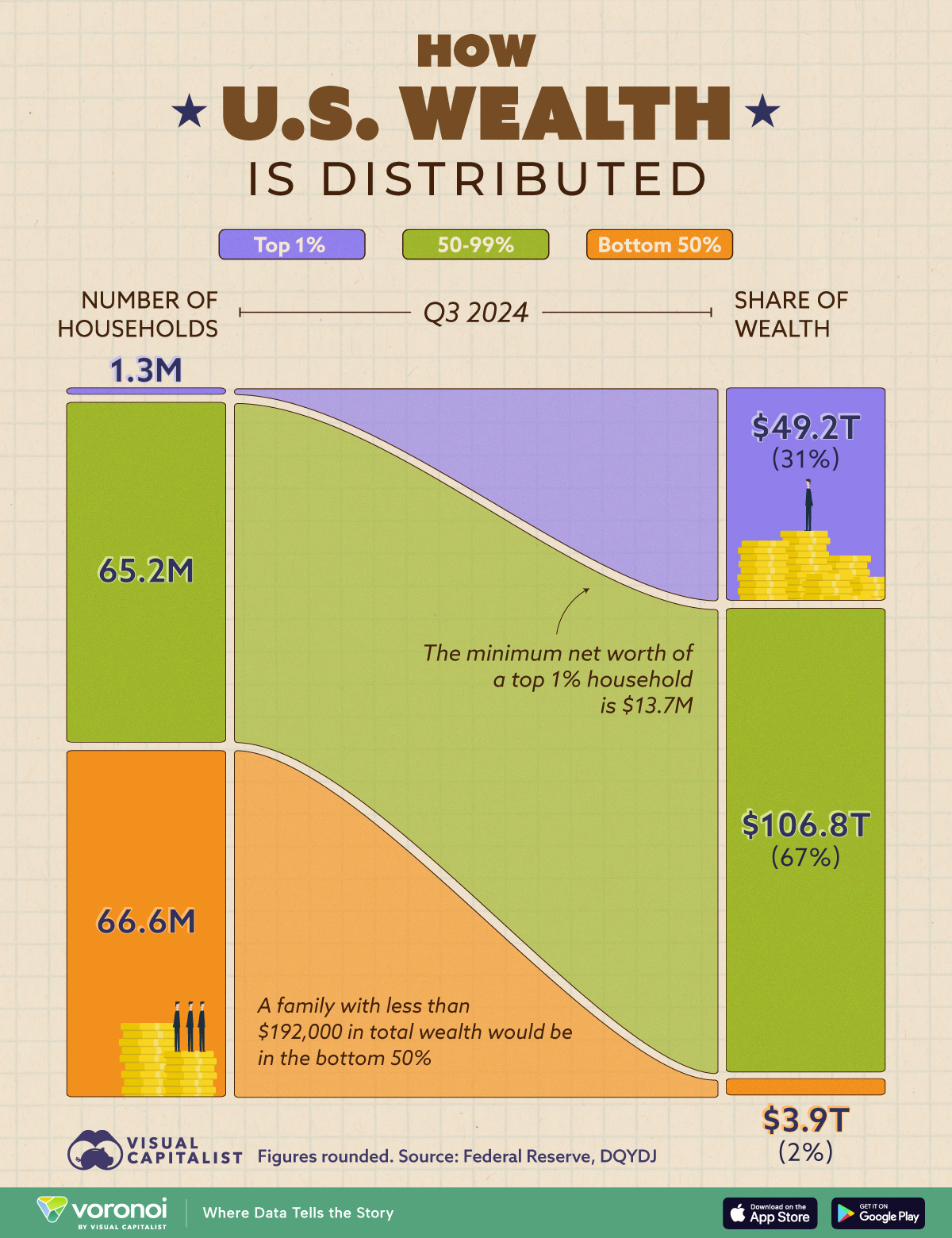

The 400 richest households in the US (overwhelmingly white) have $5.4T (up $1T from last year); do the math. “White” wealth in every stratum beneath this .000168+% begins to shrink pretty dramatically. Now lets chop off the top one percent, or one of every hundred, bearing in mind the uber-rich top 1 has 26% of all wealth, and the top .1% has 13.8% ($38.7T) Well do the race demographics again in a moment. Meantime, to qualify for the top one percent in the US, you need a minimum of $13.7 million in assets (and-or an annual income of $430,000).

Among the top one percent, 96.1% are white, even though non-Hispanic whites are 60.9% and whites (with Hispanics) are around 72%. So, yet again, the concentration of “white” people in the top one percent is throwing off the “racial wealth” statistics in the lower 99.

The average [Income—Median Income—Top 1% Income] for white non-Hispanics is $82,308—$58,802—$489,209; for blacks it is $57,836—$43,690—$283,953, for American Indians, $53,718—$40,002—$253,107, for Asians, $95,408—$65,000—$530,106, for Pacific Islanders, $54,582—$40,050—$259,100, for “two or more races,” $60,768—$42,000—$369,302, and for “Hispanic or Latino of any race,” $50,547—$37,000—$265,002. But again, this set is thrown off substantially by the concentration of whites at the very top, meaning it overstates (by inference) the degree of “racial/economic” difference among the 99 percent.

This is not to say that there aren’t statistical “racial” differences remaining with the subtraction of super-wealth, but that these differences diminish the lower you go on the assets/income scales.

Using poverty statistics, 36.8 million Americans subsist below an artificially low “poverty line.” 42.4% of them are “white.” In raw numbers, that’s 15,603,200 people to add to any class coalition, who are run off by talk of white skin privilege… that’s the difference between academic theses/virtue signaling, and strategic thought… why would anyone alienate more than 15 million potential allies?

Race/wealth statistics, or “racial inequality” discourse, has a problem: race-versus-class is a false dichotomy. An old debate teacher I had back when I was a road guard at the Red Sea told me that before one ever enters into a debate, he or she needs to read How to Lie with Statistics, by Darrell Huff. I’ll do a quick analysis of wealth inequality now, comparing white and black in the US, again not because there aren’t other groupings, but to give one example of how deceptively constrictive statistics can be.

Race here is an accepted category used in various “race-ethnicity” surveys, based on how people “identify,” whereas “race” as a biological category is rac-ist drivel. Race is an organizing principle and the basis of solidarity in various struggles precisely because this phony biological category marks actual people. Race may not be a biological reality, but it is inescapably a historical and political one. If you don’t like it, or it’s inconvenient to your ideology, so sorry. It’s real.

In the United States, one percent of the population holds around 40 percent of the wealth. The top ten percent holds 70 percent of the wealth. So, 40 percent of the wealth for one out of a hundred, and another 30 percent for the next nine out of a hundred. It just gets worse from there. Rather than batter you with more numerical breakdowns, I’ll use this graphic:

Yeah.

By 2012, three greedy assholes— Jeff Bezos, Warren Buffett, and Bill Gates—held wealth equivalent to the bottom 50 percent of the US. That’s well above the average for the top 1/100 of a percent.

The US has 643 billionaires. Among them, African Americans total six: Jay-Z ($1 billion), Kanye West ($1.3 billion), Michael Jordan ($2.1 billion), Oprah Winfrey ($2.6 billion), David Steward ($3.5 billion), and Robert Smith ($5 billion). (The above figures have jumped dramatically. Between 2012 and 2024, the worlds ten richest increased their assets by $64 billion.)

Jay-Z: 1

Gates: 89

Subtract one white dude with $89 billion and add $6,000 per person to 148 million white people. THAT is how the racial statistic gets thrown off by the top.

Most of these figures have changed, opening the gap further, during and after the pandemic. Forbes wrote in 2022 that after the pandemic hit, “the total net worth of the 643 U.S. billionaires climbed from $2.9 trillion to $3.5 trillion. During the same period, 45.5 million Americans filed for unemployment.”

[NOTE: All the foregoing statistics are belied by the fact that, among the super-rich, the majority of their wealth . . . assets . . . whatever . . . are held as financial instruments—stocks, bonds, derivatives, etc. (rentier assets)—which are, essentially, fictional values. I wrote a longish bit on this here, so no reason to digress; but what has to be said is that, as fictional value, these assets are fragile. A drop in the markets or a liquidity crisis can wipe out billions overnight. I couldn’t give less of a shit if rich people lose in this casino—they can sell their car collections for more money than I’ve ever had in my life; but after the Glass-Steagall firewall was removed between savings/loan institutions and speculative finance, our mortgages and pension funds got stirred in with this risky business, which has forced the government to repeatedly bail out the speculators (including buying up their shitty assets).]

While black poverty runs around 30 percent, and while white poverty runs at around 10 percent, when you factor in that whites are 72 percent of the population, there are 7.8 million poor black people in the US and 19 million poor whites. Among the extremely poor, below half the value of the (artificially low) poverty line—20 million plus—42 percent are white, and 27 percent are black. So yes, black people are still over-represented among the poor. But there are still a hell of a lot of poor white people, none of whom would recognize their “privilege.”

When we note that white families hold 90 percent of the nation’s wealth, that does not mean that most white people are wealthy; it means that tiny fraction of white people own most of the wealth and they drive the numbers up within the statistical category, making the rest of white folks en masse look more well off, using race-only statistics, than most really are. Remember, this series on American black history is focused on political strategy, something most academics—and I’m sorry my dear academic friends—wouldn’t recognize if it bit them squarely in the ass.

Again, no one is saying that white supremacy didn’t exist or that white advantage doesn’t statistically exist. On the contrary, anyone who wants to delve into the archives of what I’ve been writing about for the last quarter of a century will find that white supremacy has been nearly an obsession. What I’m saying here is that race and class are not some antagonistic binary, and that neither can be sufficiently understood without factoring in the other. It’s an intersubjective race-class tension, that must be recognized, but not totalized or allowed to interfere with or subvert effective strategies.

Five years ago, I watched the ruling class co-opt the slogan “Black Lives Matter” from the movement by the same name in the wake of the mass uprising sparked by the police murder of George Floyd. That was followed by targeted grants to any number of NGOs who then colonized this message and solid it back to people as a lifestyle . . . a way of diverting attention away from class and economics and trying to stuff the whole issue into a “racial diversity” package.

Ten percent of US households hold 77 percent of the total wealth in the US. Ten percent of African American households have 75.3 percent of all US black wealth. Looks close, and it’s important. There’s race in that class, and class in that race.

The bottom ninety percent (race irrespective) is losing ground right now (mostly through debt and inflation) . . . and fast. Is there a disparate impact in a society organized around white supremacy? You bet. Can black economic distress be reduced to race? Not unless you ignore those 19 million poor whites. Can you talk about these racial disparities, or the targeting of black and brown communities by the criminal justice system, without including “race”? Not unless you can ignore the “race” statistics on police abuse and incarceration.

What constitutes class? Studied as a relation in good post-Marxian form, most of us are working class. That’s not determined by a number, but by whether or not your household depends on someone working for a wage . . . or aspiring to work for a wage because they have no job. Everyone in this category, hold up your hands. Roughing this out, that’s about nine out of ten. Of the remaining ten percent, we have that one percent owning stuff, and another nine percent who work for salaries for the one percent—the “retainer” class outlined above.

What’s the character of a wage job, apart from working for an hourly wage? Here’s the critical thing: it means your boss owns your ass while you’re at work, because he or she can fire your ass at will. It means you have to put up with whatever abuse and humiliation they heap on you, and you have to swallow it down like a delicious bucket of shit. So there is a structural antagonism built into the boss-worker relation. You always seek more, in an economy of scarcity, and the boss always seeks to give you less.

So, here we have a situation that defines nine out of ten of us. That is why some people—myself included—say that class is not the only category of abuse analysis, but it’s the broadest; therefore it’s the category where the most political mileage can be potentially wielded in the event that those who face this form of abuse were to get together to make the same demands.

This was the appeal the social democratic insurgency in the Democratic Party was making with programs like Medicare for All, free college, debt relief, a federal jobs guarantee, and a raised minimum wage. Each and all of these programs would substantially strengthen the whole working class in their structural antagonism with the bosses, or ruling class. We work for wages and drink those delicious buckets of shit, because we have duties and obligations to our loved ones and our own survival, and you can’t survive in modern society without money. They have it, you don’t, so stir a little sugar into that shit and slurp away. Our dependence on them for everything is what constitutes their power over us.

Debt forgiveness, publicly-funded universal medical care, higher minimum wages, free college, and jobs guarantees outside of the private market, all reduce our dependency on the ruling class, and that reduces ruling class power. What did Democrats talk about? Entrepreneurialism and diversity. (What did Republicans talk about? Bad immigrants, and the libs want to take away your fucking guns.)

We live in a time in which all our lives are dominated by massively powerful monopoly corporations, and yet we focus on a mythical, marginal figure—the entrepreneur.

Now is the time when I attack the scam-ideology of entrepreneurialism—a political self-help racket that ruling classes sell to subalterns to trap them in a competitive, self-centered delusion that makes them self-alienate, work their asses off, and suck up to power.

It’s attractive, let’s face it. Social democrats want to raise wages and promote unions, and MAGA wants to rebuild American manufacturing, but the truth is . . . no one wants to be a line worker. Of any kind. It’s alienating, mind-numbing, and monotonous. The only reason anyone wants “a job” like this is because we live in the aforementioned, monetized economy of scarcity, and it’s a question of economic survival. There was a reason that so many well-paid union members back in the day were raging alcoholics, heading straight to the bar after punching out (this was called working class culture, instead of working class self-medication). I grew up hearing about the “Budweiser clock.” No kid fantasizes about the assembly line. The alternative they’re fed through entrepreneurial propaganda is becoming “a success.” Even most people who begin life as a proletarian—speaking for my native country, the USA—have every intention (often without the knowledge or capacity) to “work their way up” . . . somehow.

Professor Benjamin C. Waterhouse of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill wrote a very useful book about it, called One Day I’ll Work for Myself—The Dream and Delusion the Conquered America. (Interview here)

This crackpot ideology has the most traction during periods of extreme precarity. It’s promoted by anecdotes from the exceptional few and sustained by wishful thinking that conceals the competitive reality and its very real material and economic limits. The period of the most immense popularity of capitalist self-help book by people like Norman Vincent Peale was during the Great Depression. In today’s precarious times, the pop-delusion includes the tech-entrepreneurial bunkum that is now consolidating techno-feudalism. (You can launch a reaction channel . . . You can set up a Substack publication.) When the economy is failing, the perception of general institutional failure makes the idea of “doing it on your own” doubly attractive. The politics of aspiration meets acquisitive individualism.

Black history in the US, as described in earlier installments, has been infused with the politics of respectability, and that with a perpetual and forceful stress on aspiration and fashion. Understandable, given the history. Respectability is a quest for social esteem. Aspirational appeals are an attractive psychological antidote to grinding precarity and obdurate racism. Fashion—one might refer here to the history of “black dandyism”—is a means of asserting a counter-identity in the face of economic and cultural devaluation. On the other hand, these values can outlive the conditions that provoked them and become independent, subcultural norms (that come with increasingly steep retail price tags, serving as another form of enrichment for the business class).

Gradient sunglasses, velour tracksuits, high-dollar shoes, designer biker jackets, nameplate jewelry, Kangol bucket hats, colorful blazers, Yves Saint Laurent “black power” nostalgia outfits, Gucci T’s, sleeveless swag hoodies . . . this stuff costs a lot of money. Then again, money is the marker of success, and success is the marker of the man or woman . . . this is where entrepreneurialism lays at the intersection of respectability, aspirational boosterism, and fashion.

What the dream merchants never say is that a rare few actually succeed, because . . . capitalism. There’s little room at the top, and that top depends upon having a large exploitable base underneath it. Entrepreneurism sells books and makes the careers of ‘influencers,’ even as it fills its consumers with false hope and, eventually, bitter disappointment … to actually succeed, like the exceptional few, one will sacrifice a lot, beginning with time (think eighty-hour work week).

(The alternative, which I myself tried for a while during my first break in Army service, is “alternative economy” entrepreneurialism. i.e., selling illegal self-medication commodities. That entrepreneurial enterprise was shut down when my brother went to prison for entrepreneuring with a police force confidential informant.)

Entrepreneurialism is a natural fit with the politics of lower taxes and deregulation. For its aspirants, it means a lack of labor protection and no health insurance. Entrepreneurial ideology is a vector for hyper-materialist individualism and, combined with racial uplift ideology, entrepreneurialism replaces real social solidarity with identitarian cheer-leading.

The Democratic Party loves entrepreneurialism. I remember Hillary Clinton’s cringe-worthy attempts at “negro whispering” during her 2016 Presidential Primary campaign. She used the word “entrepreneurship” in front of black audiences more times than I could count, then jumped the shark with her comment, “I’ve got hot sauce in my bag,” cribbed from the Beyonce song, Formation. This, from the daughter of a Northern white suburban businessman and former Goldwater girl.

I wonder about what happens to the “entrepreneurial self” as a person, one who feels obliged to fit herself to the expectations of others to the extent called “marketing oneself.” What it is, in fact, is self-exploitation. But that’s another theme for another day.

Let’s look at the ultimate paragon of respectability and exemplar of black political aspiration: Barack Obama.

“The interests of black elected officials and the black political class in general are not necessarily isomorphic with those of a ‘black community,’ no more than is the case with respect to any politicians and their constituents in the American political system.”

—Adolph Reed

Historical recap . . . during Reconstruction, African American civil society germinated among self-help groups, schools, churches, funeral societies, cooperatives, and other formations. The general belief (though not totalizing) was that African Americans might be eventually incorporated into the surrounding society as equals.

With no access to the means of production, however, upward mobility was restricted. The emergent African American sub-bourgeoisie did not control banks or factories, and so could only engage in entrepreneurial activities that remained dependent on credit from white financial capital and supply chains from white productive capital. Wealth within African America was accumulated by church leaders alongside retail and service enterprises — barber and beauty shops, funeral homes, corner stores, etc. Big capital (the white 1/10th of one percent) cashed in from afar, concealing their presence behind black bodies, but retaining all power by holding the financial and material means of production—which means the material necessities for building, stocking, maintaining, and running (at a cost) small entrepreneurial enterprises.

These were the upwardly mobile families that learned two things: first, you have to be able to work with suppliers (white folks), and second, your credibility depends on performing white respectability. The latter emphasis on respectability politics remains powerful today. In 1998, Randall Kennedy wrote about the struggle for respectability in African America:

A . . . core intuition of the politics of respectability is that, for a stigmatized racial minority, successful efforts to move upward in society must be accompanied at every step by a keen attentiveness to the morality of means, the reputation of the group, and the need to be extra-careful in order to avoid the derogatory charges lying in wait in a hostile environment.

This kind of grasping at respectability, especially among classes of people who are trying to “move up,” for whatever group in whatever time, is not primarily motivated by economic concerns; money is a means to an end, but the goals are status and acceptance. This grasping for status, however, has powerful economic consequences. Respectability, s noted above, has fashion and consumption codes; but they materially demand the circulation and accumulation of money. Respectability, then, lives inside the epistemic architecture of capitalism, and its closest material companion is consumption.

Complicating an already contradictory situation is the struggle of any “subaltern community” to overcome the dominant narrative of innate inferiority and its attendant self-loathing and loss of self-esteem. The fightback against these conjoined phenomena includes “proof of equality” strategies and the quest for paragons. (One particularly horrifying “proof of equality” project was “The Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male.”)

In a world of limitations, the most privileged, talented, and driven will press into those arenas which are available. In the US, those available arenas for racial paragons have been entertainment — whether media or sports (often the same thing) — both of which remain dependent upon “white money.” Now, some few African Americans are actual members of the haute bourgeoisie, and identify with its interests completely, which means stability in a system where the subjected status of African America is built into its structures.

Politics has also become one of those arenas . . . Democratic Party politics, that is, for our day and age.

Barack Obama went to law school, worked in non-profits, and rose up as a political figure inside Chicago’s “Daly machine.” Comfortably bi-racial, with an uncanny practical political instinct, he fitted himself into that bourgeois racial demilitarized zone where the one-percent celebrates its own diversity without challenging the structures of capital still dependent on the broader stability of capitalism, the current American form of which carries historical racial disparities forward into the financialized (or Wall Street) economy, to which Bill Clinton decisively wedded the fortunes of his party.

Barack Obama didn’t have an agenda, he was the agenda.

—Touré Reed

Barack Obama became, as the first African American head of the American state, a racial paragon. And I cannot dismiss this . . . our own “biracial” children (and “multi-racial” grandchildren) were buoyed by his victory, and it gave them — and millions of other black kids — a refreshed sense of their own potential. Symbolism is not mere. It has material force.

Obama was not only a paragon and a symbol. He fitted in with a form of African American political conservatism that is still dominant. It is not ideological conservatism, but tactical conservatism. In 2016, in spite of her racial dog whistling against Obama in their primary contest, and her “hot sauce in my bag” gaffe, black voters broke strongly for her against Sanders, not out of any love for Clinton, but because they were convinced by the claim that Sanders was un-electable in the General against Trump.

Joe Biden’s 2020 candidacy was a perfect example or this. Black people of my generation knew damn well that Biden was one of the chief attack dogs against Anita Hill, that he was an apologist for racist opposition to busing, that he promoted the carceral state, that voted consistently for war, that he peddled influence, and that he could, even before his dementia, drift into incoherence at the drop of a hat.

The political calculus — possibly from long association with the multiracial Democratic Party — is based on a linear-continuum theory of American politics. The theory goes: there is an ideological left, a center, and a right — equally populated by the white majority — and that to win against the right (read, hostile racist Republicans), it’s necessary (as a form of collective self-defense!) to have candidates that are marginally better than Republicans who can “appeal to the (white majority) center.”

This is a niche-protection strategy, and it’s generational. As a rule, the older we get, the more firmly we are committed to our beliefs and the more conservative we become with regard to dramatic change, or the threat of it. One thing that most, older Democratic voters agree on—white, African American, and other—is this linear-continuum theory of American politics. Because, for a time, it was true during that generation’s most politically formative years.

The problem is that it was true only with respect to defeating the rightmost right-wing electorally. This culminated with Bill Clinton, who, once elected, rode the speculative wave of the nineties to sustained popularity (a highly leveraged speculative orgy that went bust a few years later under Bush with little modification), and has not worked since. Gore, Kerry, and Hillary Clinton all crashed and burned. Obama defied the trend with a powerful grassroots ground game and strong youth and African American support — riding Hope-and-Change to victory against dreadful Republican opponents who were strapped to the Bush II legacy like a giant shit-bomb (as Republicans are now with Trump).

There’s no doubt that Obama was a skilled politician, as well as a skilled orator, and a man who, with his family, exudes respectability. “They’re such a classy family.” It’s a potent mix, and all of us can remember how people admired the First Lady’s social skills, civility, and decorum . . . which has come into stark relief as a comparison with Trump’s family of addicts, narcissists, psychopaths, opportunists, mashers, thieves, and bullies.

The irony is that black respectability — once seen as a way of gaining white acceptance — has not won over white society except among a fraction of white civil society that was already in Obama’s camp. As African America performed respectability all the way up into the Oval Office, the most reactionary fraction of white society has abandoned respectability altogether in favor of a politics of revanchist intimidation.

It was an easy transition, because behind the public political scenes, this white revanchism remained to one degree or another in the background of black life in America, even with a select group of black leaders and influencers invited into the champagne rooms of the capitalist retainer class.

All of this is new and not new. There is an echo of the historic struggle within African America here, between the ideas and practices of accommodationists, separatists, and rebels — each of whom presented compelling narratives. If we think back to W.E.B. DuBois, Marcus Garvey, and Booker T. Washington, we can find it. DuBois embraced a race-conscious class struggle narrative, but only after a period of race-elite boosterism under the theoretical rubric of “the talented tenth.” Garvey was one of several popular “entrepreneurial” separatists. Washington was an “entrepreneurial” accommodationist. Of all these, it’s easiest to denounce Washington (from this far distance) for being unmanly or whatever; but we have to bear in mind that Washington did not see the struggle as between rebellion and accommodation — as DuBois had framed it. These debates were backgrounded by waves of lynching. Washington saw the choice as one between accommodation and extermination. It’s never simple.

Right or wrong, this is also the essence of tactical political conservatism. There are still black communities where this stark choice is closer to the surface than any white community can fully comprehend. White “progressives” would do well to get their teeth into this reality and not let go. There is a lot more to reasonably fear from dramatic change of any kind for poor communities than there is for coffee-shop revolutionaries.

Surely we remain aware of the ways we who opposed Clinton in 2016 and critically supported Obama in 2008 and 2012 had to call out Obama and Clinton on their dreadful policies on the one hand, while defending them against attacks that were explicitly sexist and racist on the other. (In 2024, we felt obliged to vote for Harris, who was actively supporting a genocide!)

It was always a delicate dance for anyone — especially white folks — to criticize Obama. Obama-as-paragon and Obama-as-symbol were not going away. Because, while it should not be a totalizing idea, it’s still important. And I will say this to the chagrin of some, but white people have less standing to judge on this account (as I am doing now). Nonetheless, this has to be understood and further elaborated as part of a shared political reality, especially in the context of strategic discussions as we enter the era of Trump 2.0.

What is interracially shared is (1) a ruling class, (2) money-dependency, and (3) the state. What is not shared, or partially-shared, is a great deal of lived experience. Even in our multiracial family, the white members do still have a different experience of the world outside our homes.

That background is changing. For starters, the capitalist end-game is coming into view right now — with runaway climate catastrophe less than two decades away, the house of financial cards growing higher and more precarious, and a resurgence of fascistic political tendencies (capitalism will always rely on the mailed fist in the end).

Given: the present-day African American political establishment has been thoroughly incorporated into Democratic Party politics. Given: the way up, through civil society, is an assessment and selection process.

Whether through non-profits, small businesses, or the Academy, that way up is competitive. When I was getting paid with Soros money, we were in a cutthroat competition for grant money, even against our ideological allies . . . sometimes especially against out ideological allies. Upward mobility meant pleasing the money-people, and pleasing the money-people meant delivering something in return. You have to demonstrate your ability to persuade and organize a real base. You have to have influence.

It should be unsurprising that much leadership in black communities emerges from the church. Preachers are, by definition, influencers. (And among black academics, driven by entrepreneurial ideology, business administration remains the most popular major. BA is the most popular for all “races,” but the figure is higher among black students than in any other racial category.)

Every gate upward is controlled by capital; and capital makes people compete with their peers to get through those gates. Here is a niche, if you can “earn” it. Once you’ve earned it, be aware, you can always lose it again. This demand to fit in is closely related to the respectability politics that was embodied by Obama, a veteran of the NGOs.

When Randall Kennedy — himself a promoter of respectability politics — described “the need to be extra-careful in order to avoid the derogatory charges lying in wait in a hostile environment,” he could have been describing what I saw in the non-profit world. Any black director was subject to the most vicious kinds of opposition research, something true in the larger political world as well. Any misstep drew glee from the right and “what a shame” horseshit from liberals. One particularly poisonous thing a black female friend who was an NGO director described to me was how 501(c)(3)s that were floundering would hire a black female director. The gamble was (in the “social change” non-profits) that a token of diversity might improve fundraising, and if the already-failing project went belly-up, the white liberal funders could cluck their tongues and say . . . “What a shame,” meaning she just wasn’t ready, or some comparably insipid trope. The she would be saddled with the failure, while her white predecessors would have already been hired elsewhere.

Once you’ve earned it, be aware, you can always lose it again. That’s the establishment’s finger trap. Remember, we can always shake our heads and mutter, “What a shame!”

All these interfolding phenomena, over time, have involved a trialectic between deterministic generalities and structures, particularistic histories and relations, and singular local realities, as well as the dominant perceptions and misperceptions of each era. Sometimes — in fact, most times — the perceptions and misperceptions are based on “legacy-thinking” that hasn’t caught up with existing reality except “at home.” Most legacy-thinking originates at home. That’s why belief systems are so generationally resilient. Our families were our first and most formidable interpretants of the world.

The power of legacy-thinking can be summed us thus:

I can describe with great accuracy what is going on in this room right now.

If I’m describing the town I live in, there are more legacy-thoughts — ideas about things I have formed earlier and not yet been disabused of — in my perception of the town’s realities.

If I’m describing the nation or the world, I have an even greater reality-deficit.

This temporal lag is something with a military analog.

In Korea, they fought using WWII tactics through serial failures, then in Vietnam, they fought using Korea tactics through serial failures, then in Iraq, they began using Vietnam ideas that resulted in serial failures, and so on. If the Peter Principle for bureaucracies says that “One moves up to his or her first level of incompetence,” then my own principle for these warfighting doctrines would say, “We always fail with the old tactics first.”

Legacy-thinking may be right or wrong; but what is right one day can be wrong the next. The antidote is more information in more flexibly adaptive interpretive frameworks.

The same thing applies more generally to us older folks — of all ethnicities — because we coast similarly into new realities with old ideas . . . new wine in old wineskins. President Obama’s popularity is based in part on this, too. Older white liberals are among the most ardent Obama-worshippers I’ve encountered.

Older white liberals, however, are not in anyone’s gunsights the way black people are. Their perception of Obama-as-respectable-paragon is not the same kind of paragon as he is in African America. White liberals approve of him because he is, for them, “one of the good ones,” meaning he fits white-established norms of education, polish, and respectability. He can be every white liberal’s proverbial “black friend.”

White liberals (and “progressives”) will never fully comprehend the attitude of self-defense that gives rise to tactical conservatism. African Americans cannot escape their “blackness” in this period of white revanchism, where the only political bunker seems to be the perfidious Democratic Party. And for white liberals, Obama cannot have the same meanings as he does for a people who are constantly bombarded with messages of inadequacy, who are starved for the counter-fact that a black man was once the chief-of-state for “the most powerful nation.”

Does all this lead to reflexive defenses of the indefensible? Of course. It’s an aspect of hero-worship that’s generalizable. On the other hand, what indefensible actions taken by President Obama were consistent with likewise indefensible actions by his white predecessors and successors? It’s a negative defense, but sometimes that’s what you have. And yes, Obama substantially strengthened the executive security-state power that Trump has now inherited.

Let’s return now to class relations. As I suggested earlier, the US ruling class is all about diversity these days. There is no problem bringing a few “people of color,” a few women, and a few sexual minorities into the ruling class. As long as they understand their duties and responsibilities. In fact, the more vulnerable on other accounts the better, because people are going to protect their niche . . . they will conform. They will not rock that little boat. And the boat they’re not rocking is built around a framework of class inequality.

In 2020, we approached a crucial election, faced in the immediate term with the necessity to rid ourselves of the self-serving pyscho-infant in the White House, and faced with the longer (but still short) term crises of political reaction, climate destabilization, ecocide, mass migration, civil wars, financial collapse, and now we can add war between nuclear-armed powers and the Palestinian genocide.

Not everyone was aware of how immanent these crises were — in many respects they are already here. Ruling class perception managers were hard at work to provide us with the rationalizations we needed to reassure ourselves that we were good people and that things would somehow work out. They’d already been effective at convincing most of us that they’re motivated by more than the desire to accumulate, by some Pollyanna version of the common good (that only incidentally requires us to buy their shit).

The persistence of Joe Biden’s popularity in the face of his personal history was in part attributable to his association in the popular imagination with President Obama. We already know, some of us at least, that the ruling class, embodied in part in the Democratic Party establishment, knows how to tip their spears against the left with women, sexual minorities, and “people of color” — how to weaponize identity. And that works to an extent. But just as importantly, or more so, Biden was the tactically conservative choice as legacy-thinking led us back to the linear continuum theory of elections. The most effective tactic employed by the Democratic Party against the Sanders insurgency was “he’s un-electable.” This was the main takeaway for African America.

Seldom mentioned, Obama tactically selected Biden as running mate/VP precisely to appeal to that mythical white center that leans slightly to the right. And this might suggest that it worked because of that tactic. It was not. President Obama was the beneficiary of a confluence of factors, including that phenomenal ground game, strong establishment backing, really incompetent (and loony) Republican challengers, strong youth support, and record turnouts among African Americans. Given his margins of victory, that five percent for victory was the shifting white center — which included the Obama-Trump voters.

Obama-Trump voters were those who voted for Obama in 2008–2012 then switched to Trump in 2016. The white-right center represented by Biden was insufficient to account for Obama’s victory . . . but this 2016 defection from Obama to Trump (13% of Trump’s vote!) was determinative of Hillary Clinton’s 2016 debacle.

The reality, which flies in the face of our legacy-thinking, our old wine in the new wineskins, is that this fraction of voters, who rejected Clinton but would have substantially supported Sanders, and who finally voted with Trump, hated “free trade” agreements, had experienced decades of Democratic neglect and bullshit, and they registered their boiling resentment in a fuck-you-all vote for Donald Trump.

Sanders was the guy who called for . . . universal medical care, free college, debt forgiveness, and public works jobs projects. All the things that would have most rapidly improved the lot of most black Americans, and all the things opposed by the Democratic Party establishment, including and especially Barack Obama.

During the 2020 Democratic Primary, we saw the perfect example of the trialectic of Obama’s continuing influence, the uses to which the Democratic Party puts black tactically conservative voters, and the power of the black political class.

In 2020, ex-President Obama completed the sabotage of the Sanders campaign just prior to Super Tuesday with a phone call to South Carolina’s 6th District Congressional Representative Jim Clyburn.

The summary of that call: Endorse Biden now!

On Super Tuesday, much of the South votes at once; and all the Southern states with large African American populations and Republican white majorities (which vote Republican in the General) decide—using “the African American vote,” who will get that huge block of delegates to the Democratic National Convention. Clyburn and the rest of the black political class, now historically positioned to be decisive in Democratic National Primaries, got the message loud and clear.

Obama’s power was overwhelming, given his unshakable popularity among the majority of black voters and the fact that the bloc of black voters now had the limited but substantial power to select Presidential nominees.

This power, however, is a based on mutually assured destruction — the Democratic Party as institution versus African America’s voting bloc. Each can kill off the other by walking out. They are bound together, because they can no longer exist without each other, even if and when the Democratic Party establishment forgets most of African America—though never forgetting or neglecting the black political class—once they’re in office.

The Democratic Party itself is an institution in deep crisis with a lengthening track record of political incompetency. Black leadership within the Democratic Party and its civil society cohort are now in the unenviable position — only years after African Americans gained real power within the party — of being locked into a room with a bomb . . . or a corpse. The real danger is that when this moribund party fails — barring a social democratic takeover and makeover — African America might be left politically homeless in an increasingly dangerous milieu.

The insularity of the ruling class means the ruling class perceives “through a glass darkly.” As society becomes less stable — and we are inside a deep political crisis in the US — the old epistemic architecture shudders on its foundations.

After 2020, the DP was strapped to Biden (even as the Republican party was strapped to Trump) like a bomb. A party of both neoconservatives and neoliberals (don’t be fooled, neoconservatives are neoliberals who love wars), the only thing that inched them across the finish line in 2020 was a highly contagious virus. And in a weird historic shuffle of the political deck, the Democratic Party became the security state party, and the Republicans became the political Mau Maus.

The security state became the Democratic answer to Trump. This failed. His devotees don’t follow the rules, and even the rule-breaking is a cause for celebration by the Trump cult — a fraction within his coalition that includes white proto-fascists, many of whom fantasize about race war . . . and genocide.

I shouldn’t have to say this, but the electorate is not particularly political, not in the way people who read political blogs are. It was grinding insecurity and a magma dome of anger, post-2007–8, that hyperenervated voters to Democratic political bullshittery. (This was added to Rust Belt anger building since 1991, when so-called “free trade” agreements gutted the unionized manufacturing base, and precipitated the mass migration of Latin Americans to the North.) We’d heard politicians spout glittering generalities and obvious equivocations while doing jack shit for decades. Part of Trump’s appeal, especially among that Obama-Trump voter fraction, but more generally as well, is what-you-see-is-what-you-get: that mysterious quality called “authenticity.”

For the record. I think “authenticity,” as now too commonly employed, is just one more linguistic example of our simulacrum-based cultural rot. Good actors can perform authenticity, and one of those good actors was/is Barack Obama. Other politicos are less skilled actors, and they fail: Hillary Clinton, Beto, Newsom, Harris . . . they’re B-grade actors. Biden is an anomaly here, because he was one of those people who couldn’t act at all, and kept forgetting his lines (something closer, surely, to authenticity, as in authentically incapable). Trump likewise forgets his lines, but he’s, like many malignant narcissists, comfortable in front of an audience as an extemporaneous bullshitter—like a tacky Vegas front man . . . which appeals to large segments of the American body politic, who’ve been narcotized for a lifetime by televised imbecility . . . from coked-up game show hosts to “reality” TV. Raised for decades on cheap, materialistic, brain-dead entertainment, we voted in a cheap, materialistic, brain-dead entertainer. Go figure.

The authentic guy was Sanders, a grumpy old social democrat who’d sneaked into the US Senate through a crack in the American political architecture (he won his first mayoral election by a single vote).

In 2024, the Democrats tried to run a Weekend at Bernie’s campaign with Biden, but his (pitiful, really) performance at the first '“debate” with Trump led the Party to coronate Biden’s identitiarian VP pick, Kamala Harris—whose dismal showing in the Democratic Primaries apparently didn’t phase the DLC nabobs. They’d already settled on their strategy—the same from 2016 until today: run against Trump.

The Obama summer home in Martha’s Vineyard

With the rise of reaction in the US, defectors from the black political class have become counter-celebrities. The old Democratic Party in blackface has been met by its opposite. From Clarence Thomas, we can work our way through ever-more-influential black “conservatives” like Tim Scott, Candace Owens, Kanye West, Ben Carson, Burgess Owens, Condoleeza Rice, Harris Faulkner, Deroy Murdock, Thomas Sowell, Allen West, Horace Cooper, Cherylyn Harley LeBon, Byron Donalds, Brandon Tatum, Charles Payne, Larry Elder, Katrina Pierson, Star Parker, Shelby Steele, Lawrence Jones, and more.

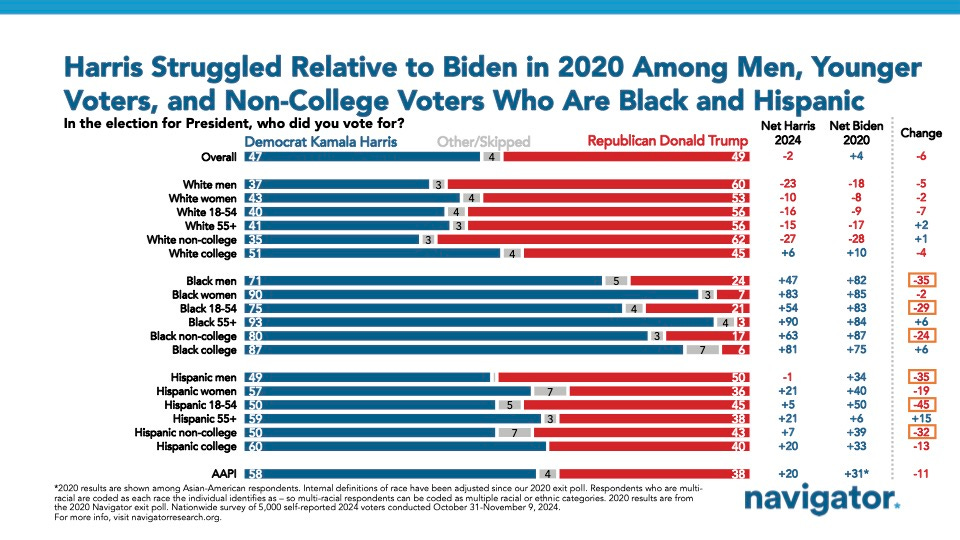

The reason these black Republicans are ever more effectively reaching black voters are varied, but chief among them includes (1) a visual demonstration of a disassociation between Republicans and their former negrophobia, and (2) growing discomfort among blacks, Asians, and Latinos with the liberal assault on traditional values. Statistically speaking, these are culturally conservative demographics. Strategically speaking, this is a slow moving disaster for Democrats that revealed itself in a Republican trifecta in 2024.

Let’s use one striking example.

Yes, it’s back. The issue of “transgenderism.” (For my very long form research piece on this, click here.)

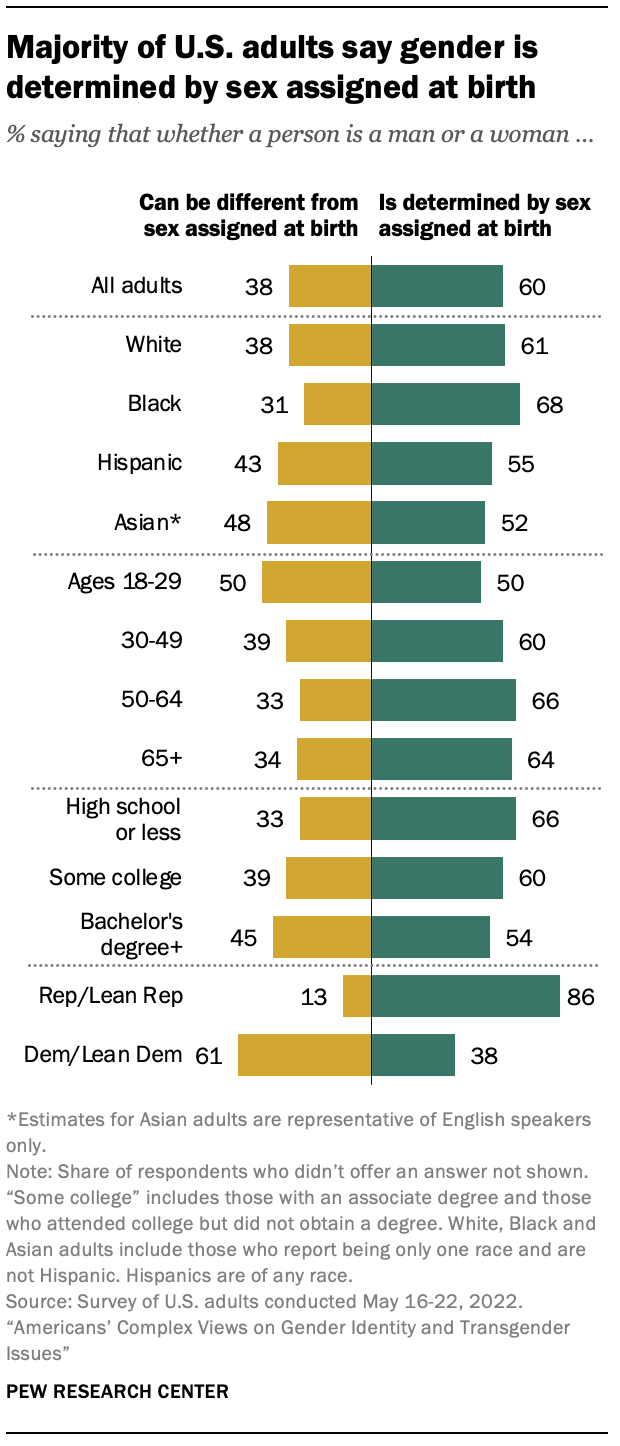

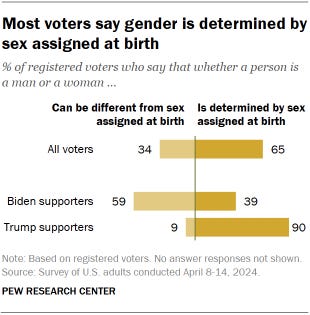

Pew did some research in 2022 that showed my own views on the matter to be concordant with majorities. Sixty-four percent of Americans believe those who claim to be “transgendered” should have equal access to public spaces and jobs, for example. But majorities also think trans-identified biological males should be prohibited from competing in women’s sports, and that kids under eighteen should not be given hormones and surgery to “affirm” their belief that they are the opposite sex. It is not, then, hatred or phobia, but the rejection of what—to most—is obviously an evidence-free ideology, and the desire to protect youngsters with unformed minds from pursuing surgical and pharmacological mutilations that will leave them sterile and drug-dependent for the rest of their lives.

Overlooking the fact that Pew is engaged in trans-ideological advocacy (by using the loaded term “assigned at birth”), subtracting white Republicans from the category “white,” and rejecting “Hispanic” as too broad to be meaningful (as a purely linguistic category), one can see that African Americans reject the baseline presumption of gender ideology. The only category in which there a majority accepts the “born in the wrong body” shibboleth are Democrats. The Democratic Party, without African Americans who constitute around 19 percent of their total numbers overall and hold the key to victory in highly urbanized blue states, is no longer a viable political institution.

From 2016 to 2022, black Republican voters were around nine percent of the Republican vote. In 2024, Trump pulled 16 percent of the black vote, the highest percentage for any Republican in the preceding 48 years. He also made big gains among the more amorphous “Latino” vote.

Let me not oversell the “trans” issue here. The main issue for the overwhelming majority of voters was inflation (and an attendant polemical preoccupation with immigration). And there is a substantial gender divide (meaning male v. female) around Trump. His belligerent macho performance attracts a certain fraction of men and repels a big fraction of women (who see in him their own abusers). But the difference in the popular vote was two percent. Winning or losing is determined by “swing” votes. That is where genderwoo made the crucial difference. (They know it, too, even as they deny it . . . AOC pulled her preferred pronouns off her Congressional bio not long after.)

Looking at the last graphic, we can see that on this issue—one which affects people’s children—the Democrats are in the hole in almost every single demographic, including a college education. The big exception: “religiously unaffiliated.” Mostly Democratic voters. Mostly white.

On March 2024, Joe Biden infuriated millions of Christians by commemorating March 31st (Easter Day that year) to be “Transgender Day of Visibility.” Yes, it’s ridiculous, because the trans thing has become more visible than the stars. And yes, its been around since 2009, but this was an election year in which the issue had already become a stick the Democrats handed the Republicans to beat them with; and the Republicans—very predictably—picked up the stick again.

The point is—remember we’re looking at black history through the lens of political strategy—we may be seeing the first signs, in an less than ideal way, of the breakup of Democratic hegemony among black voters and the dissolution of the power of the black political class. It’s hard to predict where things go from here, because all models for political calculation prior to the last decade have been thrown into a state of disorder.

I don’t mean this only applies, as it obviously does, to the reorganization of the Republican Party or the terminal stasis of the Democrats. There’s a polycrisis, as Edgar Morin called it, outrunning the forms and methods of politics of which these parties are a part.

In the WEF diagram above (assembled by Adam Tooze), we see only five “risk categories, to which we must add—in thinking through our capacity to address the polycrisis—both political inertia and the metaphysical crisis.

By political inertia, I mean we are on the Titanic, a ship whose rudder is too small for its mass. By metaphysical crisis, I mean the very economic and technological web within which we’ve been collectively formed is rapidly erasing the philosophical resources we most need to grasp what’s happened to us. This fatal combination of events outrunning political systems and the desertification of the intellect (in favor of sterile technological calculations) is a grave prognostic indicator for an increasingly stochastic political future. Most can’t understand it, and even though some do, the metaphysical crisis is atomization, that is, there is no shared metaphysical ground from which to effectively confront the magnitude of the polycrisis. We are near or past some ineffable point of no return.

We’re in the throes of an imperial catastrophe, with technofeudalism on deck, echoing the rise of an earlier post-imperial feudalism except for the fact that we’re also running headlong into a atmospheric/biospheric crisis that has no precedent prior to the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction. (Technofeudalism is Yanis Varoufakis’ analysis of the rentier-gig economy, where we produce alone and pay tribute to digital feifs.)

American politics is now the love child of an auction block and cheap “reality” TV. Trump won the 2016 Primary and General, with the enthusiastically idiotic assistance of the Democratic Party, by becoming an internet troll. You can look at him now in his incoherent public performances, and he is uncannily tranquil. He has no more sense of historical import than a sales-slicker or a computer-addicted booger-roller in his grandparents’ basement. One man contributed over $300 million to his campaign; and lest we think this is a Republican thing, remember how Michael Bloomberg spent $936,225,041.67 in a three-month campaign for the Democratic nomination in 2020 just to blunt Bernie Sanders.

These people are like flies consuming a fallen body before it’s dead; and we’ve been reduced to consumers and spectators.

This, of course, explains in a broad way the bizarre characters we get as a result of social atomization and political inertia, but we still need some coordinates to make sense of this moment, apart from my doomeresque arc of history. Christopher Bickerton and Carlo Acetti may be the people (not sure) who coined the term “technopopulism,” which I find somewhat helpful.

It’s what happened, re Bickerton and Acetti, to describe the rise, post-1990s, of a technologically-supported faux-populism that sprang up in the presence of generalizing precarity and the disappearance of mass/civic institutions (like the ones who were the wind under the wings of the Civil Rights movement). Technopolulism grew, under the radar, in response to an ever more atomized populace losing trust in the technocratic (neoliberal) institutions of both cultural production and governance.

Institutionally grounded populism versus ungrounded (atomized) populism! In the latter case, there is no mediation between leader and mass, and without the leader, the mass loses all adhesion.

In 2016, we saw insurgencies against the two major American political institutions—Republicans and Democrats—by leaders without institutional bases: Sanders and Trump. One (a billionaire TV personality) prevailed against a weaker party apparatus, and the other (an irascible small-state Senator) was crushed by it; but in they heyday of each, there were never supporting mass institutions as mediators . . . or safety nets absent the Beloved Leader (Laclau’s “empty signifier”). MAGA completed a takeover of the party, then rehabilitated its power from within via political success; while the Berniecrats, once their leader was gone, floundered then dissipated, leaving us with an opposition party that was strong enough to defeat insurgency from the left, but increasingly too weak (and too stupid, frankly) to challenge the threat arising on the right.

To go back a bit, technopopulism isn’t this “authenticity” obsessed, unmediated relation between the Great Leader and the atomized, insurgency-energized populace, but the ways in which the present order’s institutions respond to (and eventually, incorporate) that energy, with varying levels of success. (Who can blame us for our authenticity obsession, when politicians so often behave like AI robots? Or when we all—chained to our machines—harbor suspicions about our own authenticity?)

The character of populism is inherently antagonistic. There are allies and enemies. This distinction lies at populism’s heart. The difference between right-wing populism and left-wing populism is that the former enemizes groups along non-economic demographic lines, and the latter enemizes more clearly along economic lines. In the abstract, The Enemy becomes -isms, -ocracies, -archies, and -ations.

The trigger for populism is precarity, expressed as “social self-protection,” understood as “our way of life.” It matter little to people that in the past 500 years, and especially in the last 200 years, “ways of life” are wadded up and thrown in the trash with increasing frequency. As Marx observed in the nineteenth century, “All that is solid melts into the air,” as capitalism “advances.”

Technopopulism is not technological populism (even if Trump’s trolling may qualify for that name), but technocratic populism. It’s the fusion of a populist politics with the existing technocracy. The New Deal, driven by populism-with-institutions, had powerful technocratic elements. The Tennessee Valley Authority, as one example, was technology (electrification), but it was overseen by a small army of technocrats (administrative bureaucrats, sociologists, engineers, and technical experts).

The fact is, the material economy is still the thesis sentence, and the reality of its leadership (finance capital and evermore tech capital) is the underline. Corbin and Sanders would have been forced into many of the same compromises as Lula, for example, had they prevailed. Just as Trump and Orban have had to and will continue to have to face the hard facts of global supply chains and too-big-to-fail rentiers who have merged with governments in a morbid codependency.

The reason the first infantile DOGE push was blunted and Musk eased out, even after his massive financial contribution to Trump’s campaign, was not merely the angry popular reaction, but the dumbfounding discovery by an incompetent cabinet of Trump sycophants (think crackpots like Tulsi Gabbard and drunken TV demagogues like Pete Hesgeth) that the techno-bureaucratic architecture of late American governance is a complex meshwork of interdependency. This pigheaded naïveté likewise led Trump himself to throw tariff threats around . . . from which he serially backtracked.

The main changes that right-wing technopopulists will accomplish will be symbolic and cultural, with—in the American case—the acceleration of environmental deregulation (which technocratic Democrats would have eased into over time).

I’m not one hundred percent convinced by Bickerton and Acetti. There are many far more granular phenomena in play that could throw off their thesis, as there are with regard to Varoufakis’s technofeudalism thesis. For that matter, big issues like the ongoing Israeli genocide of Palestinians and the European ground war in Ukraine are not factored into these meta-speculations. But they do reflect at the very least how far away we are now from the world within which Democratic technocrats imagine they still operate . . . and the imaginary past that zany right-wing populists think they can somehow recuperate by fiat.

In strategic summary: (1) political economy’s inertial mass is carrying us simultaneously and inevitably toward two (possibly three) breakdowns—one economic (the collapse of the financial house of cards) and one ecologic (biospheric calamity) (the third is the increasing risk of nuclear war); (2) the political institutions are dependent upon an après moi, le déluge financial class; (3) one of those institutions has been captured by delusional right-wing authoritarians, and the other appears to be as impervious to change as they are incompetent to resist Republican advances, while neither demonstrates any genuine grasp of (1); and (4) the populace in general has been atomized, politically deskilled, and left adrift without effective institutions as strategic political mediators.

As I write these things, I’m already anticipating the online responses: a menu of imaginary redemptions—if-only’s, wish-castings, and fictional new futures. To those, I respond: wage a successful campaign to become a county clerk or drain commissioner, then I’ll take you seriously.

The last effective popular political movements in the US died in the seventies, the most robust of them post-WWII having been the Civil Rights movement. Sorry to have been such a negative Nelly at the end. If you have ideas to solve the problems of tribalism, atomization, and the loss of popular institutions, please . . . pour them out. We’re paralyzed.

As to ancillary discussions, let a thousand flowers bloom. Critiques, please, have at me. It’s time to close, at last. Black history in the United States has been our line of march for this series, and the focus on political strategy has provided the compass. I hope it’s helpful (it has been for making me to clarify my own thinking). I’m done. It’s yours now . . .

. . . carry on.

Peace